My Favorite Classic Games, Part 13

These games might or might not be masterpieces; the criterion for this series is that they taught me an extremely important lesson(s) that made me well rounded and much stronger. I’m hoping that these games will teach you the same lessons, thereby improving your positional understanding and helping you become a better player.

Last week (in part 12 of this series, where I featured the Samuel Rosenthal–Wilhelm Steinitz game), I showed how to make maximum use of two bishops (vs. a bishop and knight). After I first saw that Steinitz game I became a huge bishop fan.

But when I saw the Heinrich Wolf–Akiba Rubinstein game (in part 1 of this series!) I realized that the knight is also a strong piece and, if you create the right pawn structure, the horse can easily prove superior to the quicker but limited (it’s stuck on one color) bishop.

What are the knight’s advantages, and what kind of pawn structure helps a knight?

- Since knights can jump over other pieces while the bishop can’t, a closed pawn structure sometimes leads to a position that’s favorable for knights.

- If a knight can find a weak square on the fourth, fifth, or sixth ranks (a hole or support point), then the horse will often be equal to or better than a bishop.

- A bishop is stuck on one color squares, while a knight can reach any square on the board. This means that nothing is safe from the knight.

- In the case of lower-rated players, a knight is simply trickier -– it jumps all over the place and confuses the opponent so much that a bad move or even a blunder can occur at any moment.

A lot of people ask me, “What is better, a bishop or a knight?”

At the grandmaster level, bishops tend to be more useful in the majority of cases. But grandmasters are pragmatic, and though some might have an affection towards one piece over the other (for example, Petrosian preferred knights while Fischer was a true master of the bishop), they will quickly toss “affection” aside for what’s best in the given situation.

Since the bishop is not a particularly flexible piece (it’s stuck on one color) while the knight is both flexible and tricky, the knight (in my opinion) is equal or even superior to the bishop in amateur chess.

That’s why I ignore new iterations of point count (it was originally created for amateurs and is only useful for amateurs), which should factor in that extremely important point. I view the three points for both the bishop and knight as perfectly viable, while anything that gives a higher numeric for the bishop is completely missing point count’s purpose.

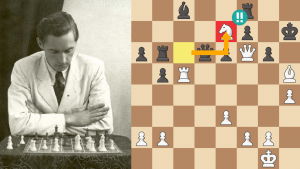

Returning to our study of knights, let’s let Fischer give us a helping hand. In 1970, Fischer (the guy that loves bishops) played in a strong tournament in Buenos Aires. I was following the tournament news as closely as possible, and once the games in this event were published I went over every one.

Of all the games, though, the one that captured my attention the most was his victory over Damjanovic. Fischer was a bit worse in the opening, and as he tried to win by complicating things, he became seriously worse. Then, just when Damjanovic could have made maximum use of his two bishops, he made an epic mistake that turned a super bishop position into a superior knight position!

From that point on Fischer completely outplayed his opponent, equalized, kept working to turn his knight into a monster (he did this by making various changes in the pawn structure), and the resulting knight vs. bishop endgame that occurred is now legendary.

I’ll add that Fischer won this event with 13 wins, 4 draws, and no losses -– 3.5 points ahead of a field that included Smyslov, Najdorf, Tukmakov, Reshevsky, Mecking, Panno, Gheorghiu, Bisguier, and O’Kelly.

That same year, he played in the Palma de Mallorca Interzonal and was once again 3.5 points ahead of the field (15 wins, 7 draws, 1 loss), which included Larsen, Geller, Hubner, Taimanov, Portisch, Smyslov, Polugaevsky, Gligoric, Uhlmann, Reshevsky, Hort, Ivkov, etc.

Sorry! I couldn’t help reliving some of my happy Fischer memories!

For those that still aren’t buying the flexibility of the knight (and I view the bishop vs. knight battle to be one of the most important in chess), here’s one more example.

The position appears to be favorable for White due to his powerful bishop and the sad state of Black’s knight. Though White’s f-pawns are doubled, they own the e6- and e5-squares. Imagine if the f4-pawn were on the “healthy” e4-square, then the bishop would be blocked and the knight would move to e5 and rule the board.

Meanwhile, Black’s queenside pawn majority doesn’t seem to be going anywhere (and c6 is in the bishop’s sights).

However, Flohr found a nice way out of this conundrum and he actually turned the whole position on its head.

LESSONS I LEARNED FROM THESE GAMES:

- The bishop vs. knight battle is one of the most important in chess.

- Since knights can jump over other pieces while the bishop can’t, a closed pawn structure sometimes leads to a position that’s favorable for knights.

- If a knight can find a weak square on the fourth, fifth, or sixth ranks (a hole or support point), then the horse will often be equal to or better than a bishop.

- A bishop is stuck on one color squares, while a knight can reach any square on the board. This means that nothing is safe from the knight.

- In the case of lower-rated players, a knight is simply trickier –- it jumps all over the place and confuses the opponent so much that a bad move or even a blunder can easily occur at any moment.

- A knight is more flexible than a bishop.

RELATED STUDY MATERIAL

- Read IM Silman's previous article: My Favorite Classic Games, Part 12.

- Watch FM Elliot Liu's video on a magnificent knight outpost.

- Take a knight lesson in the Chess Mentor.

- Solve some puzzles in the Tactics Trainer.

- Looking for articles with deeper analysis? Try our magazine: The Master's Bulletin.