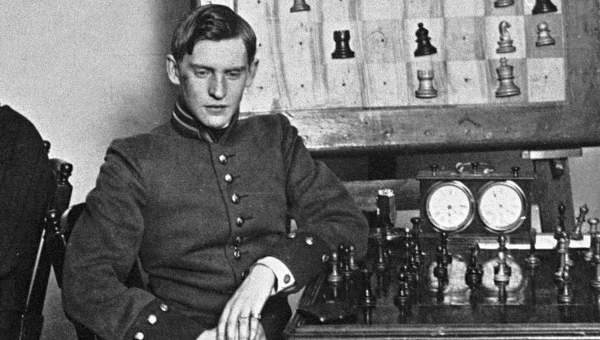

Alexander Alekhine (Part 2): Success and Despair

In Part 1 of this glimpse into Alexander Alekhine’s life and games, we left off with him winning the Moscow Championship (late 1919/early 1920) with a spectacular clean sweep (11-0) followed by victory in the first USSR Championship (9 wins, 6 draws, no losses). However, at that time Russia (and the Soviet Union which was formed in 1922) wasn’t the chess Mecca it eventually turned into, and he realized that if he wanted to be World Champion. he needed to be closer to his competition. By 1921 he was living in Germany.

The Plan

With the World Championship and nothing but the World Championship on his mind, he mapped out a clear plan: Play against the world’s best and win every tournament, thus showing that he was the true challenger to the title. And, at first he would also avoid Capablanca until he felt he was closer to him in strength.

This strategy was already “on” as far back as 1914 when, before accepting a place in the Mannheim tournament (which he eventually won), he wired the organizers and asked, “Inform me, please, if Capablanca is going to play in the tournament.”

The organizers, who thought that Alekhine wanted to compete against Capablanca, were embarrassed since the Cuban wasn’t going to play. However, Peter Romanovsky, after joining Alekhine in Mannheim right before the event, asked him why he sent that wire. Here is Alekhine’s reply:

“If Capablanca participated, I would not play. I must train for my match against Capablanca in the coming years to become the World Champion and there is a trick. I must win, come in first, in every event. So far, I’m weaker than Capablanca and this means that if he took part I’d come in second. This does not fit my plans.”

Note that as far back as 1914 Alekhine knew that Capablanca would eventually take the title from the aging Lasker. Thus Capablanca was his ultimate target and he never took his eyes off of him.

On Top of the World

After dominating his final two Russian events (as mentioned above), he continued his collection of first prizes: 1st – Budapest 1921 (6 wins, 5 draws, no losses, ahead of powerhouses like Gruenfeld, Tartakower, Euwe, Bogoljubow), 1st – The Hague 1921 (7 wins, two draws, no losses, ahead of Tartakower, Rubinstein, Maroczy, Euwe), 1st – Triberg 1921 (6 wins, 2 draws, no losses, ahead of Bogoljubow, Saemisch), 1st – Hastings 1922 (6 wins, 3 draws, one loss, ahead of Rubinstein, Bogoljubow, Tarrasch).

In these events Alekhine showed wonderful opening preparation, his usual tactical genius, an incredible imagination, solid positional skills, and surprising technical expertise. Here are a couple examples of his play in 1921.

The first example shows Alekhine’s brand of active defense. In this position White, who intends to play for the central advance e2-e4-e5, appears to have the advantage since it’s hard to find Black’s counterplay. Alekhine refuses to play passively and instead sacrifices an Exchange for a myriad of plusses:

The next game demonstrates Alekhine’s extremely original vision, which allowed him to come up with ideas, even in the opening, that other players would never see:

And here we see Alekhine as a dynamic monster... a human tidal wave that washes his famous opponent away:

Here’s an example of his dynamic endgame play. White has a queenside pawn majority while Black has a central pawn majority. However, the key feature is Black’s superior activity. One would think that White should be able to draw this position, but Alekhine’s play overwhelms him.

And finally, here’s a purely technical endgame crush, demonstrating the vast superiority of knight over bishop:

Fall From Grace

This was an incredibly busy schedule and the stress of having to win “first and only first” must have been overwhelming. However, his plan was working and everyone saw Alekhine as the only worthy challenger to Capablanca’s title (the Cuban finally got and won a match with Lasker in 1921). When a super-strong tournament in London was organized, Alekhine decided to toss away his “no Capablanca” rule and duel with the World Champion face to face (other participants were Vidmar, Rubinstein, Bogoljubow, Réti, Tartakower, Maroczy, Yates, Euwe, and others). When the smoke had cleared, Alekhine had the magnificent score of 11½ out of 15 games (8 wins, 7 draws, no losses) but, alas, it was only good for clear second since Capablanca finished with an outrageous 13 points (11 wins, 4 draws, no losses).

Though it was clear that Alekhine was the second best player on earth (barring Lasker, who wasn’t interested in regaining the title), finding sponsors who would put up the money for a match had always been far from easy. Unfortunately, another occurrence at the London event made things even more difficult for Alekhine and anyone else that wanted to challenge Capablanca.

The London Protocol

During the event Capablanca got all the top players together and took them to one of London’s top hotels. There he plied them with expensive champagne and asked them to sign a document (called the London Protocol), approving Capablanca’s proposed rules about future World Championship matches. This is what grandmaster Milan Vidmar, who wanted to challenge Capablanca, had to say:

“I clearly remember the most important rules of the so-called London Protocol. The challenger must, first of all, raise $10,000 [That’s $132,717.34 in present day currency. – Silman]. In addition, he must defray the travel and food expenses of both players. Another rule required that the winner receive $6,000 and the loser $4,000. There were several more clauses to protect the current World Champion.

“It was funny that, while signing the London Protocol, it did not occur to me that my youthful projects had been shattered and that my dream of winning the World Championship would never come true. It should have been clear to me that I did not have the slightest chance of raising $10,000 for my challenge.”

Emotional Collapse

In my view, Alekhine’s disappointment of coming in second behind Capablanca mixed with the near impossible demands of the London Protocol proved severely debilitating to a man who was already under enormous stress. When he failed to win his next event, Pistyan 1922 (= 2nd behind Bogoljubow, with 12 wins, 5 draws and 1 loss), he must have gone into a deep depression. Thus it isn’t a surprise that the following tournament, in Vienna, was a total disaster – he tied for 4th through 6th (1st – Rubinstein, 2nd – Tartakower, 3rd – Wolf, 4th with 6 wins, 4 draws, and 3 defeats was Alekhine, followed by Maroczy and Tarrasch and then Gruenfeld, Réti, Bogoljubow, Spielmann, Vukovic, Saemisch, Takacs, Koenig, and Kmoch).

Alekhine started the event well, but it quickly became clear that his nerves were shot. He rushed his play, he blundered, he botched one good position after another, the balanced style he created over the previous couple of years had reverted to overt aggression and risk taking… put simply, he was a total mess.

Butter Knife Blues

And now we come to a hotly contested tale. According to a friend of Alekhine’s, a certain Mr. Edmond Lancel, Alekhine was frustrated and lonely after his last sub-par performance. And this led to an attempted suicide! Here’s the tale:

“Alekhine rested for a few days at Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen) – I also happened to be there. We had seen a good deal of each other since the beginning of the year and, while in Aix-la-Chapelle, we spent time together at an evening party celebrating his birthday at the hotel Corneliusbad. He shared intimate details of his private life and pictures of his loved ones. We played, as we did from time to time, several training games in preparation for the great Vienna tournament. All of a sudden, in a fit of despair with no previous warning, Alekhine attempted suicide by stabbing himself in the belly!

“It was about 3AM and the main hotel lobby was deserted except for the two of us. Alekhine collapsed lifelessly at my feet. I summoned the hotel personnel: the manager, a physician, the ambulance, and the police and whoever else was needed. Things seemed grave, and Alekhine remained unconscious. However, thanks to prompt and efficient assistance he came to. A few days later he recovered.

“This event, just a few days before the Vienna tournament, was not without significance. I spared no effort to dissuade Alekhine from participating for I was convinced he would do badly. But there was no keeping him from competing, and he achieved one of the worst results of his career.”

Of course, this story can’t be proved or disproved. And, since chess historians tend to accept what can be verified (understandably), most refused to believe it really happened. However, I feel that there is a very good chance that this did indeed happen. In fact, even one or two of the following points have led many people to end it all:

- Depression

- Overwhelming stress

- Failure (in his own eyes)

- Loss of a life dream

- Loneliness (a common occurrence for an expat)

- Facing a situation with no end in sight

A momentary impulse is all it takes...

I should add that Mr. Edmond Lancel wasn’t some unknown person. He was the editor of a lovely chess magazine called L’Echiquier Belge, he was known to be close friends with Alekhine, and a couple of his games against Alekhine were published. On top of that, Mr. Lancel also published a book that was co-authored by Marcel Duchamp. It’s hard to find a more credible witness.

Mr. Lancel, out of respect for his friend, didn’t publish this account of what occurred until after Alekhine’s death (keeping this secret while Alekhine was alive is something a good friend would do). I see no reason why such a highly thought of, respectable person like Mr. Lancel would make this up.

And so we’ll leave Alekhine in a bad situation. In our next installment we’ll see how he throws off the chains of despair and does something that most people felt was impossible.

Before looking at our puzzles, I’ll offer up one of Alekhine’s greatest games:

It’s games like this that led the present number two player in the world, Lev Aronian, to call Alekhine the greatest player who ever lived.

Puzzles

[Most of the puzzles offer invisible prose and variations. After you try and solve the puzzle, click SOLUTION followed by MOVE LIST so you can all the hidden goodies.]

Puzzle 1:

Puzzle 2:

Puzzle 3:

Puzzle 4:

Puzzle 5:

Puzzle 6:

Puzzle 7:

Puzzle 8:

Puzzle 9:

Puzzle 10:

Puzzle 11:

Yes, the same game as above, but this time we are looking at the finishing blows.

RELATED STUDY MATERIAL

- Read Part 1 in this series about Alekhine;

- Watch GM Melikset Khachiyan's video Defensive Tips: Active Counterplay!;

- Watch GM Dejan Bojkov's video about dynamic play;

- Check out GM Dejan Bojkov's Chess Mentor lesson about knight vs. bad bishop;

- Read IM Bryan Smith's article The Young Alekhine;

- Watch GM Roman Dzindzichashvili's video Greatest Chess Minds: Alexander Alekhine;

- Improve your tactics in general (always a good idea!) with our Tactics Trainer.