The Player I'd Most Like to Have Met

Throughout the history of the game, chess has produced innumerable fascinating personalities. Some were stars, others played supporting roles. Many of them, at least from the hazy vantage point of my clouded rear window, could capture my attention were I granted the opportunity to spend a few hours with them.

Choosing just one player of old for that mystical visit is more than difficult. Would I pick George Walker, the early 19th century English font of information, or maybe Paul Morphy whose genius was bookended by courtesy and kindness? Perhaps the witty, hard-working Joseph Blackburne, the suave, handsome José Capablanca or the intense and affable Mikhail Tal would fit my bill. The more attention I gave the fantasy, the more my compass jitterbugged in the unlikely direction toward Israel Albert Horowitz.

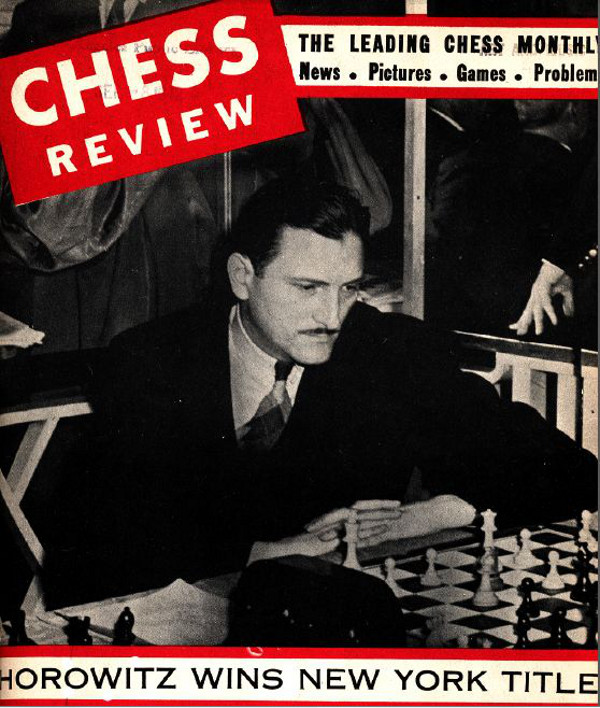

Best known to most people today as an author of novice and intermediate books as well as the founder and editor of the popular and long-lasting periodical, "Chess Review," Horowitz lived in a fascinating time which he helped create as well as record.

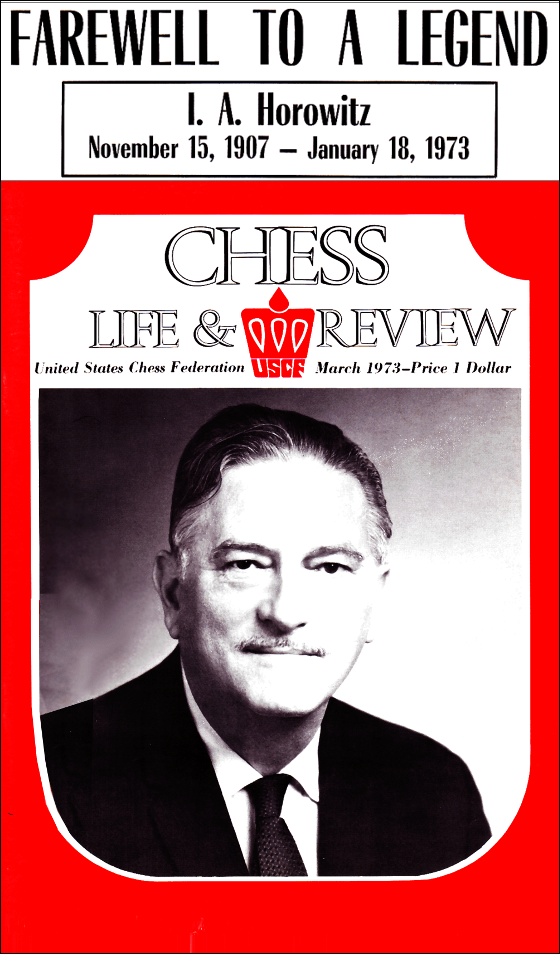

Louis Horowitz' son, Albert, came into the world on November 15, 1907. He died at the relatively young age of 65 —a lifetime of heavy cigarette smoking exacting its revenge— on January 18, 1973, the same year I was born. Perhaps that partly explains my affinity.

"The Pittsburg Gazette," Feb. 25, 1939 informs us that Al played his first game of chess at age eight and that during his four years at NYU, Horowitz "lost only one match - to a man named [John] Vanderslice who is now Albert Einstein's protoge." According to "Recollections of Princeton" by Malcolm Robertson, 1984, "Vanderslice, besides being the chess champion, with his incredible memory, would whistle whole symphonies and concertos of Beethoven, Brahms, and Tschaikovsky, to our applause and appreciation."

Herman Helms, in his "Brooklyn Eagle" chess column on Aug. 20, 1942, wrote, "Horowitz played his first chess [presumably, competitive chess] at the old Commerical High School, now Axexander Hamilton. He won the interscholastic championship. For four years he captained teams at New York University, 1925-8."

After earning his business degree from NYU, Horowitz took a white collar job at the investment house of Holt, Rose and Troster. The same "Pittsbugh Gazette" article as above tells us, "He once tried working in Wall Street. Howard Holt, a big broker, decided that expert chess players would make good traders and hired some of them. They did very well, but Mr. Horowitz decided to make a little on the side investing his own money. He lost it."

Larry Evans claims Horowitz found that once the Depression hit, Wall Street work became untenable and Horowitz deduced "that if he could win a quarter a game and 'a quarter could buy a meal,'" chess would support him better. So, Al Horowitz abandoned Wall Street in 1932 and in the middle of the Great Depression, and joined with Isaac Kashdan, part insurance salesman, part leading US chess player, to found "Chess Review." Since Helms was already publishing "The American Chess Bulletin," the premiere American chess periodical, also NYC-based, Horowitz and Kashdan were really putting all their cards on the table, competing for an audience during a time when money was scarce. But Horowitz was brash and daring in life as well as in chess and his magazine exuded an excitement that captured the imagination of his seemingly staid and somber target demographics.

The maiden issue, January 1933, spotlighted Kashdan:

But by November 1933, Kashan's name was gone and Horowitz was "the" editor where he'd remain for the next 36 years. November 1969 saw it merging with "Chess Life" to become "Chess Life and Review" under the auspices of the USCF.

Frank Brady, during his editorship of "Chess Life" in 1961, changed it from it's newspaper format to a more appealing magazine format, breathing new life into the periodical while making it compatible to "Chess Review," paving the way towards its merger. It's a sobering thought that Mr. Brady wasn't even born when the first issue of "Chess Review" came out.

Around 1995 I taught myself to play chess. After many frustrating attempts while using a DOS program called, CM2000, I found the book on the left, Chess: Self-Teacher, by Al Horowitz.

Using this book as my guide, everything started to make sense and I still feel a debt of gratitude to the author.

Other writers for beginners and intermediates of that day included Fine, Reinfeld and Chernev - all three of whom were at some time involved with Horowitz' "Chess Review."

Al Horowitz wasn't a benign editor or a gentleman player, but rather an ardent self-promoter and a savage competitor. That so many chess periodicals started and folded after a few issues reveals the tenuous nature of such projects. Horowitz kept his magazine afloat but never grew rich from it. In fact, Arnold Denker claims that Horowitz' book royalties went to support his magazine while he encouraged subscribers by offering free participation in his simuls to those who did. He also did somthing different by selling the magazine by the copy to non-subscribers at magazine kiosks and bookstores.

Horowitz redefined the word "barnstorming" with his numerous annual cross-country tours.

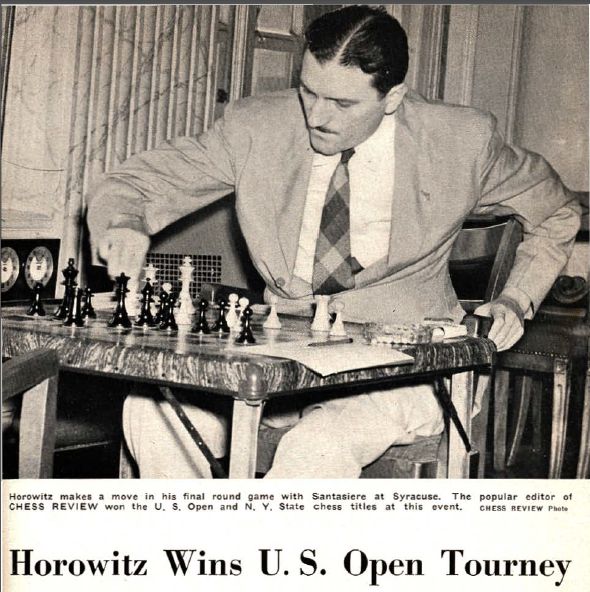

In the 30s, Horowitz played on the winning USA Olympiad teams in 1931, 1935, and 1937, always among the top scorers. He won the US Open (at that time, the American Chess Federation Championship) in 1936 and 1938 (shared with Kashdan). He also won the US Open in 1943, but experienced an intervening trauma.

The November 1939 issue of "Chess Review" posted this promotion:

This turned out to be an ill-fated venture.

According to the Des Moines "Register," on Feb 18, 1939 Horowitz and Harold Morton "of 24 Dorchester Ave. Providence, R. I.," Horowitz' current business partner in "Chess Review," were traveling eastbound on Hwy 30 and "...apparently skidded on a curve and collided with a motor van driven by Frank S. Robbins of Denver, Colo. The van turned over but Robbins was uninjured. Morton was thrown out of the car and died at once, Deputy Sheriff Witt said. Brought to the Carroll hospital Horowitz was unable to give any identity of that two except to tell his name. He suffered a basal skull fracture and his condition was said to be serious Saturday night. Deputy Witt said the papers on the two men indicated they recently had been on the west coast and were en route to Minneapolis, Minn., to give a chess exhibition. The two, according to reports here, had given recent exhibitions also at Omaha, Neb., Kansas uty, Mo., and Denver. Morton's death was the first traffic fatality of 1940 in Carroll county."

Harold Morton (kneeling left) coaching the Rhode Island School for the Deaf chess team

There was no February edition of "Chess Review" in 1940:

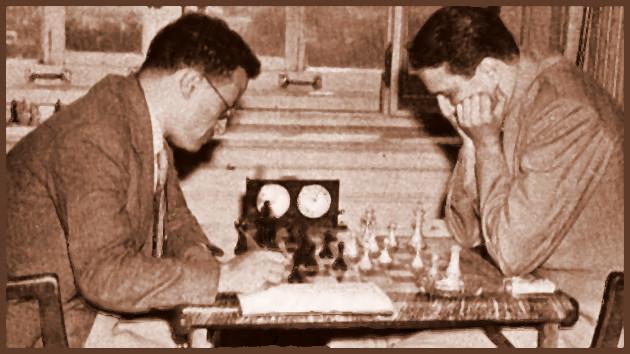

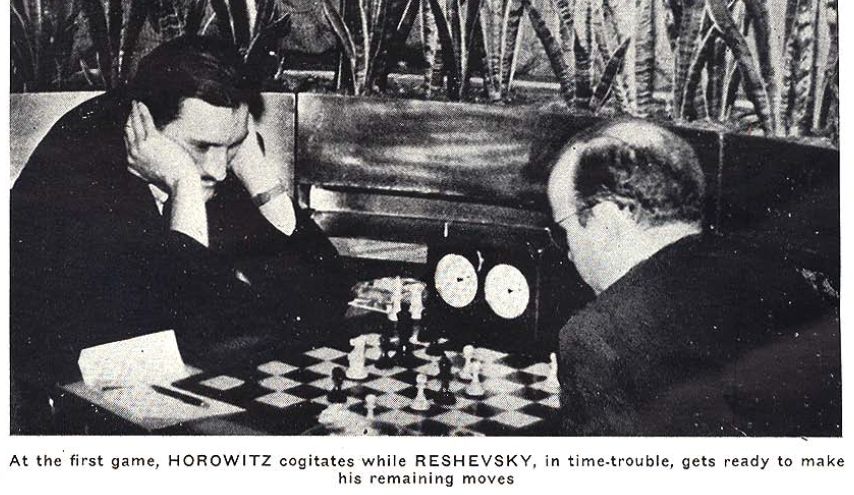

After the accident, Horowitz doesn't appear to have been very active for a while. In 1941 he played a match with Reshevsky for the U.S. Championship but lost decisively with no wins, 3 loses and 13 draws. Reshevsky was the perpetual U.S. champion during those years.

In 1944 Horowitz came in second in the speed chess contest, behind the invincible Reuben Fine but ahead of both Reshevsky and Kashdan. Earlier that year, he had come in 3rd behind Denker and Fine in the very closely contested US Championship.

More than his speed chess ability was his odds-giving facility. Arnold Denker claimed, "Next to George Treysman, Al Horowitz was the best odds-giver in the United States. He would never hesitate to grant Knight-odds to players strong enough to warrant only pawn and move. Yet he was successful thanks to psychological tactics and engaging banter, not to mention a natural genious for the game."

As shown below, Edna Horowitz also took an active role in chess, not just on the playing side, but also on the commercial side.

A shining moment came for Horowitz in September 1945 when the Soviet team crushed the US team in the highly publicized Radio Match. Herman Steiner was the man of the hour by achieving the only plus score among the 10 players (1½ - ½ against Igor Bondarevsky) but Horowitz was the only other American player with a face-saving win (1-1 against Salo Flohr). None of the others —Denker, Fine, Reshevsky, Kashdan, Seidman, Santasiere, Pinkus and Kupchik— scored a single win.

The U.S. Team

That same year, Horowitz placed 4th in the Pan-Am Chess Congress played in Hollywood. It seems he did as much sight-seeing as playing:

Al, Nigel Bruce (Dr. Watson), Edna and Basil Rathbone (Sherlock Holmes)

Unlike some of the leading American players such as Fine or Reshevsky, Horowitz has very little international experience. One exception was a rematch with the Soviets, played face-to-face in Moscow on Sept. 12-13, 1946. The palatial playing hall, coupled with the previous disastrous match must have really intimidated the ten American players, but the results were much better this time with the US winning 3 games and holding the Soviets to only 8 wins. Horowitz had 2 draws (against Bonarevsky).

A stop-over in Stockholm on September 2nd provided an interesting lightning chess match including the American players and the Swedish players. The Americans were accustomed to a 10 sec./move rapid-transit format but the Swedes played at a X-min./game. It was agreed that the games would be 8 minutes. The event took place at the Winter Garden of the Grand Hotel where the 1937 Olympiad was held before an audience of 300.

Returning home, Horowitz shared 5th-6th place with Denker in the US Championship which was won, of course, by Reshevsky. Below shows the cramped playing conditions:

Horowitz also continued making his annual barnstorming tours:

1941

1942

The "hillbilly" is Reuben Fine, pulling a surprise prank

1943

Wartime

1947 Tour

By 1950, chess in the United States had all but passed on to a new generation of stars such as Larry Evans and Arthur Bisguier. Horowitz played in the 1950 Olympiad where he scored the lowest of his team. Later he played in some tournaments but with less and less successes. Over the years, he turned more to writing.

In his own magazine he had conducted several ongoing columns such as:

and

In 1962 he started his well-known chess column in the New York "Times" that lasted a decade. It's usually forgotten that he also had a chess column in the "Saturday Review" for a time:

...filled in for Bobby Fischer in "Boy's Life," the scouting magazine:

Horowitz caught the otherwise cautious Ed Lasker in the following miniature:

from Irving Chernev's "The 1000 Best Short Games of Chess"

(thanks to my dear friend, Deb, for finding this for me)

The following game, played against the strong N.Y. player, Charles Jaffee in the 1938 American Chess Federation Congress, shows Horowitz' aggressive style:

Albert Horowitz was inducted into the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame in 1989 and a more deserving advocate of chess was never born. Al had a lot of flaws, there is no doubt. He could be brusque, unrelenting, self-absorbed and critical. He was also known to "borrow" other people's work. But, balancing the human scales were his passion and drive, his generous sharing of his time and knowledge, his tireless work habits, his humor and affability as well as his well-known ability to spin a tale. He wasn't larger-than-life, but rather reflected what it is to be human.

After too many years of indulging in his favorite N.Y. hot dogs and hot pastrami sandwiches, his 3-pack/day cigarette addiction and his avoidance of anything even resembling exercise, his body just surrendered on January 18, 1973 and Chess lost one of her most irreplaceable servants.