How To Battle The Caro-Kann

In the previous two articles, I have discussed the earliest beginnings of the Caro-Kann Defense as well as later usage and developments. In this third part of the four-part series, I will discuss the various methods White has evolved to oppose the Caro-Kann.

While the entire Caro-Kann, practically from its inception, has had a reputation for solidity, the kinds of positions that can be reached in White's various options differ greatly -- from closed, maneuvering struggles in the Advance Variation, to wide open positions with rapid piece play in the Panov-Botvinnik, to the "half-center" type of positions in the main lines.

Thus there is no clearly defined best-regarded approach against the Caro-Kann, unlike, for example, the Sicilian Defense, where the Open Sicilian with 2.Nf3 and 3.d4 is clearly in the lead in popularity and respectability.

White's choice in taking on the Caro-Kann is largely a matter of taste.

We will now discuss each of White's main approaches.

The Exchange Variation:

The Exchange Variation against the Caro-Kann consists of 1.e4 c6 2.d4 d5 3.exd5 cxd5 followed by simple development (NOT 4.c4, which constitutes the Panov-Botvinnik Attack, a completely different approach). As we saw in the first part of this series, this was one of the earliest responses to the Caro-Kann. This was in keeping with the times, when open positions were preferred -- for instance, the Exchange Variation was also frequently seen as a response to the French Defense.

White was typically not successful in getting an advantage in those early games. The position resembled a reversed Queen's Gambit (the exchange variation), and Black's position was very solid. Typically he succeeded in developing with ...Nf6, ...Nc6, ...Bg4, and ...e6.

Soon, some improvements were made -- in particular, by tweaking the move order, White put obstacles before Black's development of the Bc8. 4.Bd3 was the main way to play the exchange variation, meeting 4...Nc6 with 5.c3 and then 5...Nf6 with 6.Bf4 (rather than 6.Nf3, which would allow the pin 6...Bg4.

A few strong players did use the Exchange Variation, but for the most part nobody regarded it as more than a way to avoid theory and just play chess.

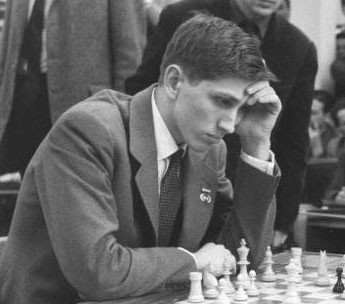

They heyday of the Exchange Variation was probably after its use by Bobby Fischer against Tigran Petrosian in the 1970 USSR-Rest of the World match, where Fischer played a model game.

In fact, Fischer's name is often associated with the Exchange Variation, although he only used it one other time.

Since then, the Exchange Variation has had reasonable popularity, although some consider Black's approach with ...g6 and ...Bf5 to be a total solution:

Nevertheless, the Exchange Variation remains a viable practical weapon, particularly for players who want to avoid heavy theory.

The Two Knights Variation:

Although considered a sideline, there is no way you can say that developing the knight to f3 rather than playing d2-d4 (1.e4 c6 2.Nc3 d5 3.Nf3) is eccentric.

Despite a seemingly small difference between this and the main line, it often results in widely different positions. The first point is that Black really cannot play the same as in the 4...Bf5 main line (1.e4 c6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 dxe4 4.Nxe4 Bf5). In this case, the earlier development of the knight to f3 makes all the difference, as the very first game (that I know of) with the Two Knights Variation shows:

While this "trap" might be a potential attraction to the line, the main point of the Two Knights Variation is to avoid 4...Bf5 altogether. Thus the majority of Caro-Kann players who meet the main line in this way have to find another way to play against the Two Knights Variation. In practice, this means that people who play 2.Nc3 and 3.Nf3 typically end up facing 3...Bg4 most of the time.

White usually meets 3...Bg4 with 4.h3, after which Black can choose between the risky retreat 4...Bh5 and the more usual capture on f3. In that event, White's play revolves around his two bishops. There can be interesting play resulting, sometimes with White castling queenside and pushing g2-g4-g5.

The Fantasy Variation:

The much beloved "Fantasy Variation" occurs after the moves 1.e4 c6 2.d4 d5 3.f3:

At first glance, this move 3.f3 looks strange, which makes it more surprising that this was a relatively early method of meeting the Caro-Kann -- it was recommended in an 1890 article by Kurt von Bardeleben and played for the first time in the same year in the game Harmonist-von Bardeleben.

While the move 3.f3 breaks a number of principles (for instance, it weakens the white king's position, does not develop a piece, and blocks the f3-square for the white knight), White argues that the Caro-Kann's relative lack of pressure on the white center allows White to get away with it.

Thus the pawn on e4 is maintained, and for Black to vigorously counter-attack he must open the position, in particular the f-file, for White's benefit.

The move 3.f3 got its name due to the "fanciful" variation that can occur when Black takes the central counterattack to its logical conclusion:

This was exactly the course of one of my own games, Smith-Everett, Anchorage 2002; and a few others.

While the strategic goal of maintaining the pawn on e4 is quite valuable, the price White pays is quite high, and this has kept the Fantasy Variation as a sideline. Black has typically met 3.f3 with 3...e6, while 3...dxe4 4.fxe4 e5 5.Nf3 Bg4 (followed by ...Nd7, ...Ngf6, etc.) and what can be called the "Georgian Variation" -- 3...Qb6 -- are all reasonable counters.

While the Fantasy Variation certainly appeals to players of a certain style -- it has, in fact, given me my best results of all the lines I have played against the Caro-Kann -- few would argue that it is the best answer, and many harbor doubts about its correctness.

The Panov-Botvinnik Attack:

Somewhat more mainstream than the options we have looked at so far is the Panov-Botvinnik Attack: 1.e4 c6 2.d4 d5 3.exd5 cxd5 4.c4

By exchanging on d5 followed by c2-c4, White transforms the Caro-Kann into a totally different type of position. Generally it leads to quite open play. Very frequently the white c- and black d- pawns are exchanged, resulting in an isolated queen pawn position.

Indeed, some variations of the Panov-Botvinnik can be reached by beginning with the Nimzo-Indian defense.

Although the names of Vassily Panov and Mikhail Botvinnik are joined to make the title of this opening variation, its biggest exponent in its early days was the world champion Alexander Alekhine.

Panov did play the opening named after him sometimes in the 1930s. For instance, the following early game went by force into a line that is still debated today:

Botvinnik had a major role in creating some of the strategic principles of the Panov-Botvinnik attack -- especially the concept of playing c4-c5, and Bb5 to conquer the e5 square, in conjunction with the exchange of dark-squared bishops. He played a number of model games on such themes, for example:

Today the Panov-Botvinnik is still played, although it has not been particularly popular at the highest level recently because White has more or less failed to find any advantage against the line featured the above game by Panov. Neither the endgame that could have occurred in that game nor Botvinnik's move 6.Bg5 (instead of 6.Nf3) have been shown to be so threatening.

Black also has a number of other ways to combat the Panov-Botvinnik attack that are highly regarded. Nevertheless, the opening can appeal to players with a healthy, open, (and at the same time) academic style, and the search for an advantage continues.

Check back next week for the final ways White can counter the Caro-Kann.

RELATED STUDY MATERIAL

- Read GM Smith's last article: The Caro-Kann: Modern Times.

- Watch GM Ben Finegold's video: Beating Your Nemesis: Crushing the Caro!

- Take a Caro-Kann lesson in the Chess Mentor.

- Solve some puzzles in the Tactics Trainer.

- Looking for articles with deeper analysis? Try our magazine: The Master's Bulletin.