Celebrating Black Excellence: An Interview With GM Maurice Ashley

During black history month, we recognize pioneers that changed the game as it was before them and made a way for those after them. Though chess becomes a more global and diverse game each year, representation at the highest levels (and FIDE titles) is still a work in progress. I got a chance to interview four black chess players whose contributions on and off the board have been directly responsible for changing the conversation around what's possible.

Below you can check out the first of these four interviews, with the man who made history by becoming the first (and for now only) African-American grandmaster, Maurice Ashley:

You can also read the transcription for the interview here:

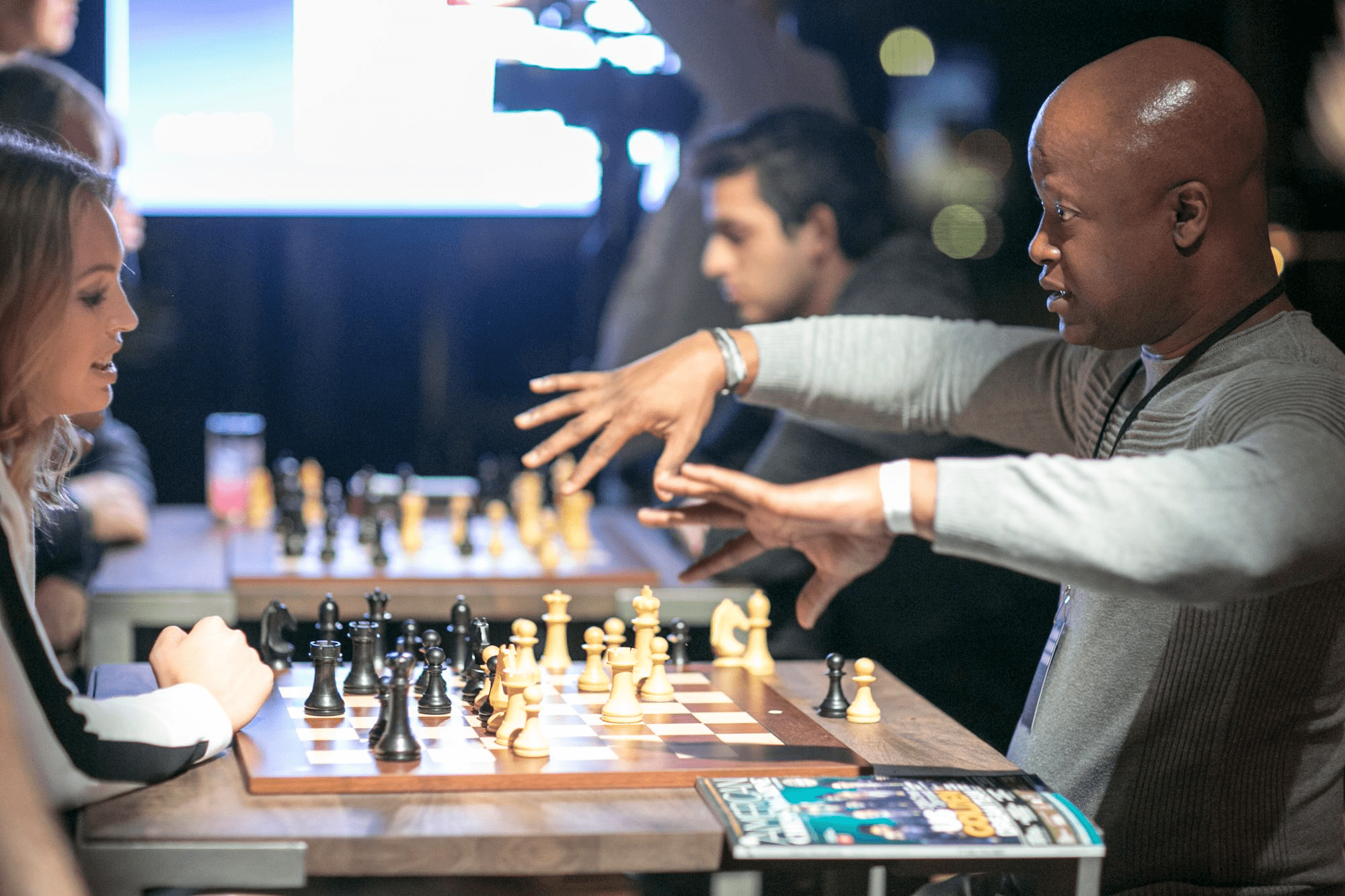

Kassa Korley: I'm very happy today to have a very esteemed guest, Grandmaster Maurice Ashley in the building. And it's just a real treat to have a sit down with you and learn maybe a little bit more than what is in the public spaces already. And, you know, being a fellow black chess player as well. Maurice is obviously a legendary figure in our community, but even beyond. And just really a pleasure to sit down and talk with you. So thanks for doing this.

Maurice Ashley: Not a problem because it's a real thrill that we're sitting down to have this conversation officially. I appreciate everything that you've been doing, and I'm certainly following your career and hoping that you get that GM title soon because I need some company.

K: Well, much appreciated. I want to take us all the way back to the late seventies when I believe you moved from Jamaica to the United States, specifically to New York. And I just want to get a sense of what those early days were like as far as your chess background and education experience. I know you had you grew up in a fairly competitive family. You had a sister and a brother that were also in competitive sports. Take me back there a little bit to Jamaica and that transition.

A: Well, I was born in Jamaica. I came here when I was 12 years old. That was in 1978. I knew a little bit about chess because we played a lot of board games because we had nothing else to do. We didn't have television until six o'clock at night. So after school, kids would play games. Chess was one of the games my brother played with his friends. I remember when he first brought the chessboard around, and I would look at it like, "What's this game?" But it was basically like checkers or dominoes or any random board game that we all played. I didn't know that there were books. I didn't know that there were tournaments. None of that occurred to me at that time. My brother said that he remembers me being very entranced by the game and playing by myself in our backyard. I have no recollection of doing that, but I do remember figuring out the four-move checkmate on my own, which later I was like, 'Wow, I figured that out.' I used it against one of his friends, one of the older boys, and I was able to beat him with the Scholars Mate. Then I basically forgot the game when I came to the US, and when I was 14, and this was in 1980, I saw a friend playing in high school, and that was when I remembered, "Oh, I know how to play this game." At least, I thought I knew how to play. I played him, and he just wiped me up off the board. It wasn't even close. Funnily enough, that friend turned out to be the uncle of Josh Colas later in time.

K: No kidding!

A: So, that's a very small world and the way things connect. But that was my first introduction to chess back then. And as you said, my family was very competitive. My oldest brother, Devon, I'm from a family of five, with two of them being hardcore competitors. My oldest brother, Devon, became a three-time world champion kickboxer. The baby of the family, my sister Alicia, became a six-time world champion boxer. So, yeah, definitely some trash-talking in that household.

K: So, what initially captured your attention with chess? Because I feel like for everyone, their maiden voyage is a little bit different. And what captivated you in Jamaica? Was it just your brother taking it up a little bit? Was it something like a sibling rivalry? What captured your attention initially?

A: It was getting my ass kicked by Chico, right? That's what it came down to. Like I said, I played a lot of games. I was always pretty good at games and caught on very quickly. And when I lost to my friend in high school, I was like, "What is this? How did I lose so easily? It wasn't even close," you know? And usually, I'm supposed to be able to hang out even with adults. That's how I thought at that time. As a young kid, I was a pretty smart kid in school. But he just wiped me out. And very fortunately, I was in the library and saw a chess book. And that was the end. I don't remember the name of the book. It would be nice if I could just put a button on the story by remembering the name of that book.

But it was a chess book. I was like, "Are there books on chess?" I checked it out, studied it, and played Chico again. He crushed me again. Turns out he'd been reading tons of books, and that started it. And that was it. It was on. I had to beat this guy. I also had a friend, Leon Monroe, who was a year older, who also went to that school, and it was just battles after that. I had to beat these guys, and I just became hooked.

K: So it sounds like you had an initial contingent of peers, if you will, at Brooklyn Tech that was playing with you, maybe giving you a hard time initially, but I'm sure after you read some books and were studying up that you soon surpassed them, I assume.

A: Within six months, I was beating Leon, who wasn't studying any books. But Chico was another story. Chico was studying. He introduced me to the chess club at school. We would go to the club once a week. Then there were strong players in the club like Stan Rosenfeld, who was already a master-level player, and others were there. So Brooklyn Tech had a pretty good chess team for a high school team back then. So I didn't even make the team. I mean, all throughout high school, I never made the team, in fact. They were always better.

Chico and I were competitive all through high school, and we started going to tournaments. It wasn't until I went into high school as a sophomore. Three years of that. And it was when I first started going to college that the big breakthrough happened, and suddenly I went from just being around 1800. My first rating was actually 1800, which shows you how competitive I was already playing in tournaments.

But then I just started jumping. And by the time I was 20 years old, I was a master player. So six years later, and then the next year, I was at 2400. And this is just with no coaching but hanging out with strong players—players in the parks in Brooklyn who are really strong, who are serious players. And then finally going to tournaments in the city of Manhattan, the Marshall Chess Club, the Manhattan Chess Club.

K: That's incredible that you actually were sort of picking up the game again in high school but didn't make your chess team through those years. But then you went on to college and were able to get better in college. I've joked around a bit with other players, and most people don't get better in college.

What was it about your drive and your enthusiasm and also maybe your unique skill set that allowed you to catch up to the competition in a way where, you know, you have these other responsibilities potentially pulling at you? I mean, typically, in college, there are other strings that are being pulled. Did you have to make some sacrifices? What areas did you make sacrifices in, ultimately, to stay on that journey?

A: College, ultimately, the sacrifice. I wanted to be a chess player. My mother wanted me to get a college degree. I had decided very quickly that I was not interested in just about anything but chess. And that's what I wanted. That's what I was in love with. That's the only thing I wanted to study. And I'm very maniacal when it comes to the things that I like. Obsessive, if you will. If I like something, I'm going to get good at it. And I don't like doing stuff I'm not good at. So I would just study all the time. I would study chess during high school hours a day, like after school. It was 'do your homework real quick, get to studying some chess, play chess after school with my friends, go to the parks in the summertime, play chess.' I mean, I was just completely obsessed by the game.

By the time I got to college, I kind of was like, "What am I doing really? I don't know. Let me pick a degree." I picked Engineering as a degree. That started being too complex and in the way of my chess studies. Finally, I switched over to creative writing, and that was easy enough to just get a liberal arts degree, pleasing my mother, if you will. That's really what it was for me because I was all about chess, and I just wanted to get better. And I think that that time I put in, those hours at reading. And I was very much self-driven. So I didn't need anybody to say "study." Or 'study to get better.' I wanted to get better. I wanted to beat all my friends. I wanted to start competing well against the masters and IMs, and GMs I saw at the clubs in Manhattan. And so I just studied like crazy. And I think it's no wonder I got better given the effort I was putting in.

K: Yeah, I always like to say that work ethic is a talent. That discipline is a talent. I want to ask you, what was your gift that helped you accelerate and edge out other people along that journey? It may very well have just been explicitly that work ethic. Some people have gifts in various areas as far as the finer points of the game, whether it's tactically or positionally, or they have some type of biases that are gifts and curses in some ways as they ascend. Did you have any of those, or would you say you were a level player, maybe a balanced player, but the work ethic was the primary gift?

A: Well, I agree 100% with you. Hard work beats talent all day. Hard work with talent is what makes champions. To me, my biggest thing, initially, and it's always been the case with me... I was a pretty smart kid, particularly in terms of math. So I loved puzzles. I love solving any puzzle you'd put in front of me. So chess was natural for my brain. It was the unsolvable puzzle. It wasn't one of those things you just looked at. Here's the puzzle. What's the solution? It was a puzzle inside of an enigma, inside of a mystery, like "What is this game?" And there was so much to it. The more you learned, the more there was to learn.

So that puzzle-solving gift that I had, or the desire, which, you know... I would do crossword puzzles back in the day as a high school kid; I fell in love with the New York Times crossword puzzles. I'd do one of those every day that the puzzle came out in the paper. I was always a puzzle solver. And I think that made it easy for me to transfer over that skill set to chess.

The work ethic was definitely there. And also, on my behalf, what was really beneficial was that I was somebody who learned from reading. I could actually digest the information, decipher what I was looking at, understand it, and then say, "Oh, I get it. I see what they're trying to say." So the more books you put in front of me, the more I caught on and the more I wanted to learn. So I consumed a lot of information just directly as such.

I've heard of youngsters who can only learn when their coaches are sitting there giving them puzzles to do. They're just not going to sit there and study the books. And not even now in the digital age. I mean, forget it. If I was a youngster now, I'd be BIG.

K: I got to say, you hear that, kids: Books! Reading! I know they're foreign terms, but they still do the tricks sometimes.

A: Well, nowadays, I understand it's a different kind of accelerated learning process using videos and chess courses and the like. But back then, I didn't get bored. I would open a book and say, "What's this?" If it's anything about chess, I wanted to know. Whether it was about endgames, middlegames... Middlegames were my forte. Tactics, love them. I actually designed my own training regimen. Like I said, I didn't have a coach.

My mother wasn't understanding—why was it that I was obsessed with this chess thing, right? She wanted me to go to school, get a degree, get a job, make a life. She didn't see chess fitting that formula, that she had sacrificed a lot to come to this country. She had left us in Jamaica for ten years with our grandmother, so she lived without us all those years, like many immigrant parents do because she had a vision for what her children were going to be.

She didn't realize that none of her kids would end up in traditional professions like her. Me being a chess player, her daughter being a boxer. She refused to even watch any of my sister's fights. And of course, my brother being a kickboxer as well. Those were her three children. My father had two of his own before they met. And we became one gorgeous family.

But this thing was what I wanted to do. I think it's Kahlil Gibran who says that work is love made visible. And that's what chess was for me. It was love made visible. It wasn't work. When it comes to chess, I have not worked a day in my life. I love this game so much that even now, when I don't have to do anything—I'm not playing chess, I'm not doing any commentary as of now. That's for now, anyway. Maybe I'll get back into the commentary gigs, but I'm still looking at chess every day. Every day. Like I was that little kid back in Brooklyn. Literally every day—creating stuff, looking at stuff, being mystified by the magic of the game. And I think that's really, for me, the biggest part of my getting better.

K: Work is love made visible. I really love that. Taking us back to the work and the love that was made visible. I want to go harking a little bit back to the development you've taken with your chess in college and then, without having access to various resources, finding a contingent of like-minded people that were working on the game. Of course, in the 80s and 90s, and even the early 2000s, you could say that New York was really one of the premier chess communities in terms of proximity, in terms of boots on the ground, in terms of people you could play within the park and so on.

I think it'd be fair to say you found some of that community with the Black Bear School, and I would love to hear a little bit more about that contingent of folks that you were playing with regularly and honing your craft with. Even though in some ways you were always going to be the best player if you did the work and you propelled within that environment, they're ultimately helping you hone your skills, and then you were going to zoom past in some ways.

A: It wasn't that obvious. The fighters you're talking about, the gladiators of the Black Bear School. Those guys were serious about chess. Hardcore. We're talking about William Morris; they call him the exterminator...

K: Steve Colding, right?

A: ... Steve Colding is another one. Earnest Steve Colding. Ronald Simpson, the late Ronald Simpson. Ronnie was a dear friend of mine, and he was, of all the members of the school, most responsible for honing my fighting skills. We would play chess at night over at our friend Mike Cox's house. It was me, Mike, Leon, and Ronnie. And later Sam Seing. And we would be in Mike's basement.

We'd roll up around eight, nine o'clock at night playing blitz. We would not leave until 9 a.m. the next morning. We're still playing blitz. We're trying to kill each other. When I tell you the ego, the pride, the fight that was in that basement, nobody would know, right? Everybody's outside partying on a Friday night, and I'm hanging out with my boys, and we are rumbling on chess, and just in it.

You had people like the late Mark Meeres, also the late George Golden. And I remember names. These are people who have passed. Nathaniel Jackson, sweet souls, man, beautiful people, Herminio Baez. These were gangsters on the chessboard. You came into the room, nobody didn't give a flying fig Newton what you were studying and how you felt. Your feelings? Keep your feelings outside, bro, because they're about to get hurt. It was just warrior chess. I haven't seen that kind of group since.

That is something that was so incredible. It was almost like Shaolin Temple, right? You were there to fight to prove yourself. And like I said, they studied. The people there were looking at ECOs; they were reading magazines in other languages. I remember Willie Johnson, who is one of my closest friends today, is 18 years older than I am. But we were kindred spirits. We call him Pop because he had a kid when he was really young. He's one of the most beautiful souls on earth. I love him like a brother. He's a soul me.

He and I are so close, but he went to Germany to be a military officer in Vietnam during the Vietnam War. And that's where he first learned about chess. So later, he had German books, and they were trying to translate German books. They were looking at Schachmaty bulletins, trying to translate Russian. How do you do this? They get a dictionary out and go letter by letter, word by word, trying to figure out what the heck is in these books.

Duncan Cox was his best friend. DC, they called him. I didn't get to meet DC, he passed the same year I met Pop, and Pop always felt like I was the gift that was given to him because his best friend DC, who was a hardcore tournament player, had just passed away. I mean, it was family. Like family when everybody's fighting for the same food, right? That's how we were.

It was not obvious that I was going to pass these guys. It only is obvious in hindsight because nobody was giving up the presidency at a Black Bear School. That's what it was all about. Who's the best? Who's on top? Nobody was just going to give it to you. You had to fight for it. You had to earn it. You had to have the heart, the spirit. You know what I'm talking about! There are some words I want to use, but I'm going to keep this PG. But you had to be ready to fight for anything that was there to get, and it mattered. And I think without them, I'm not Maurice Ashley.

K: Yeah, I certainly get the energy. And it's funny because I've joked around with this a bit in the past, but I believe I'm probably a part of them. And correct me if you disagree, but I think I might be a part of the last generation of chess players that actually grew up in parks. That ecosystem is seeing its last embers because of how digital we are, how impersonal we are today.

It is quite rare to have that deeply embedded rich chess culture and family dynamic, frankly, because you had this kind of regular, informal environment where you could conduct business. And in some ways, that informal environment was better than a lot of formal environments could be, because you were you were among kin. It's something that I can really appreciate, and in some ways, I'm perhaps a little bit envious because it doesn't exist the same way today.

A: I think you're right, I think it's a good point you make. We were kin, and it mattered. It mattered that you had these serious brothers, and they were about excellence. They were about winning. And they understood checkmate was like, "that's what it's about. It's about winning this damn game." You're not trying to pretend or learn. Just learn. You're not here just to be a spectator. You're here to win. And if you're going to win, you're going to have to do the work.

You're going to have to do not just the external work but the internal work, because your pride and your feelings and all that—that tanks, that's just going to go by the wayside. It was important to be in that space, and it wasn't formal. It's a good point because a lot of our older traditions in the black community had The Griots telling the stories. You had that oral tradition not necessarily written in books. There were times when we weren't even allowed to read books, and here we were as students trying to learn, not necessarily sharing information with one another.

Now, we'll share it with you when you get into this line of the Sicilian where I'm going to beat your ass, and then you'll go, "Oh, I can't play this line anymore." But that's how we fought, and that's how we battled, and that's how we learned. So, yes, it is a shame that that time has passed. I think you're right. Nowadays, everybody jumps online, plays bullet chess online, and, you know, even learns online. It was not like that back in the day. And with no formal teaching system in place, that was the substitute. The way that we grew.

K: Now, I want to ask you—and I'm going to contextualize this a little bit personally, because I do see some parallels with the way you got better, and then a point of departure from my experience because I had a park experience. Basically, my park was Marcus Garvey Park. I knew all the guys there, and they knew me. I was raised in some ways in that park. Of course, there's Mount Morris and some other place. But Marcus Garvey, I'm the guy in Marcus Garvey, you know.

At some point, though, those sparring partners... The highest-rated person was maybe 1700 or 1800 strength. It was not something I could continue to progress with and get better. So I ultimately operated kind of siloed in isolation, but at the same time, I had to "adjust" my game in a way for tournament play.

And you know, I'm a big basketball guy. I always make this analogy of streetball and organized basketball because there are a lot of guys that might handle the rock decently in streetball, but they couldn't, for their lives, play a game of five on five because they couldn't play defense, they couldn't slide the puppies. They don't understand concepts, and that really matters in the formalized game. And I'm wondering if there are any... even though the Black Bear school's certainly much stronger and did a lot of the formal exercises that you would expect of people that are playing tournaments, they just mostly didn't play tournaments. Was it something where you felt you had to adjust your game in any way when you actually were getting into tournament environments that were more formal, more Soviet, and perhaps at the time, more white?

A: Well, the big reality was that they didn't play as many tournaments, especially when DC passed. This is the point of departure. DC was all about tournaments, was all about preparing and battling to raise your rating and become really good. And I embodied that spirit when I walked in because I just wanted to get better. I remember people saying, "No, you have to sandbag, keep your rating low. We'll play in the world opening and win $6,000, you know, just don't keep your rating up." And I'd be like, "What are you talking about? I'm trying to become a GM. That's ridiculous!" So that mentality was something I had to escape.

This was not the Black Bear School mentality but the park ecosystem. For me, it was Prospect Park in Brooklyn. They definitely fostered this idea because it's a little bit of that hustle mentality that you keep your rating low, and you try to win some money in tournaments. But the good thing for me was that these guys really wanted to get better and be better. So when you talked about people like Mark Meeres, Steve Colding, William Morris, and Ronald Simpson, I guess those were the four who all made master, right? Not only that, William eventually became a 2500 player. Ronnie, his highest rating was 2400. Steve Colding, his highest rating was eventually 2300. Chris Welcome was 2200, those I can say with fact.

So we're talking about good players. These are not scrubs; these are not park players. These are elite chess players despite the fact that they weren't hardcore tournament addicts. In fact, the reason they became tournament addicts was because my rating started getting so high that it pissed everybody off, and a new competition brewed between us. Who was going to be the best tournament-rated player? Especially when I started beating them in blitz.

A lot of what decided strength in our Blackbear School system was blitz matches. So we played these knockdown, drag-out 30 games, draws-don't-count matches. And who would dominate in those matches? And I started emerging as the strongest, and then finally, I started really crushing them in the matches. And their egos were so huge they couldn't accept it. So they decided to be in tournaments to prove that they were as good. And that skyrocketed everybody to the actual level they were playing at and easily became 2200s to 2300s. Eventually, a couple broke the 2400 barrier.

The thing about it is that tournaments made me stronger because of the discipline you had to have to play long games. And it wasn't blitz, it wasn't quick decision, it wasn't pure tactics. You had to sit there. Like you said, you had to know your endgames, you had to be patient, you had to strategize. And that's where the flaws were in my game, even as I became a much stronger player up to the 2400 point, which I became without a coach. I was playing the English so I could mate you. Like I knew Ronnie Ronald Simpson had showed...

K: Reverse Sicilian...

A: ...Yeah, right. Actually, Ronnie showed me the variation of the Botvinnik English. Everybody looked at it and were like, "Well, he's a 1.c4 player," and they had no idea. I'm thinking about mating you. That's the point.

K: Like f4, f5...

A: Exactly. That was the plan. I didn't have many openings. I got by on what I did have, and it was pure raw tactics. And then the strategies that I was learning in books. And like I said, I taught myself, so I created a whole system. I remember when I stopped studying any tactics and I only studied positional books. I studied My System by Nimzowitsch, Modern Chess Strategy by Ludek Pachman. I did Pawn Power by Hans Kmoch, a couple of other books that were only centered on the positional aspect of the game, because I saw that I just didn't quite understand that very deeply, and I only studied that for something of a period of about six or seven months that I devoured those six books.

And then, once I had that under me, I switched and started studying only tactics. And man, I just turned into a beast. I could see where their tactical flaws were in what people were trying to do to me in the Black Bear school. From a positional standpoint, I knew I didn't have to trust it, but I also had the tactical ability, once I worked on my game to get to that point, to handle anything. It was like a natural fit for me. Once I started playing in tournaments, man, it was just like, "I can sit here all day. I'm just going to do this."

I remember the very first master I played, I beat the first. That was Danny Shapiro. The very first IM I played, Jonathan Shaw, I beat. And the very first GM I played, Andy Soltis, I drew. So for me, something about that environment was natural for me to want to battle, to want to sit there for hours. It was all about playing stronger players so that I could get better.

K: And you certainly got better. I mean, you got better through college. You got better with your skills in the Black Bear school. You got better playing tournaments, and then you're an adult still pursuing the grandmaster title in some ways. That's a totally different dynamic. The privilege of youth is something we really do take for granted as far as responsibilities and things are concerned. So how did the journey for you change or evolve as you had to take on responsibilities as a man while also pursuing your chess passion?

A: A very big thing happened to me while I was still in college. Two biggest things that happened to me, actually, that formed the rest of my chess career in many ways, or at least the next ten years. One thing was I started coaching. I got a job coaching chess, right? So I started actually making money off chess as a coach.

This was with the American Chess Foundation, which eventually became or renamed the Chess in Schools program in New York City. I got this amazing opportunity to coach chess and make my living suddenly where I was at the time. The very first salary offered to me, being a 2400 player, was $50 every hour I coached. I mean, I was like, "Are you joking?" Even today, 50 an hour is amazing, right?

K: I mean, for context again, this is also 20 years ago, right?

A: It's 30. I think this is 1989. Right? It was 1989.

K: That even goes further than it would today. That's a huge deal.

A: I only was able to coach maybe 8 to 10 hours, but nevertheless, 8 to 10 hours, you're bringing in some decent money while being in college. But the challenge there was I was in college, I was coaching, and I was trying to become a better player. Those three conflicted. That was not something that made it any easier.

K: And you have to compartmentalize.

A: Suddenly, it's just becoming a lot more difficult to become better. Then at the same time, very importantly, I got my first chess coach, and that was Vitaly Zaltsman, an international master from Ukraine who was brought up in the Soviet school. And I would go to his home in Brooklyn, taking that bus down into the Russian section of Brooklyn. You walk through and walk down Ocean Parkway. And I could see the grandmas looking out the window. "Who's that guy?", right? Trying to get to Saltzman so I could get some coaching.

I would sit in his apartment, and he would talk to me like I didn't understand anything about chess. And it became clear very quickly that the stuff that I was reading, that I thought I knew something, was not enough. My foundation was just not solid enough. And you know, he's like, what they say, "every Russian schoolboy knows." Well, every brother in Brooklyn did not know. I need to learn that stuff.

And so I would play games, I'd bring my games to him, and he just be pointing holes. "What about this? What about this? What about this? What about this?" Don't I play chess at all? And I would go home, take the bus back to Brownsville, and be thinking, "Wow, I thought I was really learning stuff before, and this guy's really schooling me."

But there was something, again, about my mind being able to catch on really quickly, and everything he told me I was like a sponge. Literally within weeks, I want to say it was months... It wasn't even like it was months. Within weeks I was on another level, and I got my first IM norm pretty quickly, just from what he was saying. It just caught on, and my game grew from that.

But then I got so much into the work aspect of things and the coaching aspect that it distracted me enough that I just didn't grow as fast. Those responsibilities you're talking about, being a grown person, they just interfered. Something was about, you know, making money and making a living, and having my own place and that kind of aspects of life. Then you start talking about meeting my future wife, and that changed things to "you got to be real." And then getting her pregnant, this was before we got married. Now you got to really be real like, "Hey, I got a baby on the way." So all that definitely slowed me down in my mid-twenties and I got my IM title, but it was a long road to the GM title after that, given the responsibilities that I had.

K: So let's fast forward slightly to that. When you were getting closer and you ultimately got there—because I believe you became a GM in 1999. Take me to that moment, to that tournament leading up to that moment. Because when you have these high-leverage situations or high-leverage moments, everyone responds to those differently. Some people fold, some people really embrace it, some people are nervous, and that's not necessarily a bad thing.

How did you deal with that moment? What were you listening to? Were you listening to music to motivate you? Who were you talking to in the evenings? Did you vent to people when things weren't going well or not? What was that situation like for you?

A: Importantly, I just had to sit back for one second. That whole journey in the in-between period between the IM title going to the GM title, a little before the IM title, I became friends with Josh Waitzkin. As many people know, he's the subject of the movie Searching for Bobby Fischer. He is 10 years younger than I am. But we became brothers. He was my new sparring partner after the Black Bear School. And he was on the quest of getting the IM title and ultimately trying to get the GM title as well.

So we would travel to tournaments together. We would play blitz at his parent's home in Soho, and the competition between us was just as fierce as what it was in the Black Bear School. So that journey, we did much of that together. We would share our failures together. In that journey, I became friends with the family, with Fred Waitzkin, his dad, Bonnie, his mother, Keisha, his sister. And I became part of that family and part of the journey. His journey, my journey, we merged. It was highs and lows for us as well. He got the IM title, never did get the GM title as he stopped playing and went on to other things. But he was hugely impactful as part of the journey as I got closer and closer to the title.

I also benefited from the students that I coached and ended up winning national championship titles, and there was a philanthropist who I worked for the organization that he sponsored. His name is Dan Rose. Eventually, the executive director of the program said: "Maybe you should talk to Dan," because I was super frustrated trying to get the GM title. "Maybe you should talk to Dan, maybe he might help you."

When I talked to him, he said, "Listen, I hear your dream. I honor your dream. You have helped us and helped these kids so much. Let me help you." That was a huge part of me being able to stop doing anything but study chess. I didn't have to work. I was only about studying, studying, studying, having a coach come to my place—Gregory Kaidanov was my coach at the time. I started to get some good grounding. But you still got to play the games.

Fast forward now to the title, the tournament I did, it was in New York, the New York International March of 1999. I had gotten my second GM norm. My inspiration was still books, reading about great players from the past, great performers from the past. Arthur Ashe, reading his life, his legacy. Jackie Robinson, who was even earlier. After reading about people like that—Malcolm X and Dr. King, their journey, James Baldwin—those are people who made me feel as if I was pursuing this history-making moment, if you will. That I wasn't really going through stuff that was that hard.

I mean, I know we were and still are in the middle of a deeply divided society where the struggle is still real for African-Americans, where equality of treatment is something you thought should have happened a century ago, or at least in the last century, but it's still happening today.

But it's not like it was. And I understood that I'm standing on the shoulders of giants, and they were absolutely my inspiration in dark moments and difficult times. I remember Jackie Robinson having a cat, a black cat put on the field, or people spitting at him and calling him names, and I said, I'm not going through that. This is my time, a different time where the struggle is quite different, and I've got that legacy to continue.

So the tournament that did it, like I said, March of 1999. I lost the second round. Drew the first game, lost the second round—on my birthday! Like, just throw the dirt on me! On my birthday, I lose in the second round. And I remember going back to my friend Pop, Willie Johnson, like I said, and it was in New York. So I just got on the phone with him, and I was devastated. It was like, "Am I ever going to get this title?" And he talked me down from the ledge. Two hours of a conversation. By the time he was done, it was back to the Black Bear School, right back to the people who love you, the people who were there from the beginning.

And by the time he was done, I was just supremely inspired. And I was back. I was like, okay, things are going to be cool. And I proceeded to win game after game after game after game. And then that last round, by the eighth round, all I needed to secure the title was a win out of two remaining rounds.

I just needed a point, and I was playing Adrian Negulescu of Romania, and that was the epic day. That was the day. I was extremely nervous going into that round. I remembered my grandmother, who had sacrificed so much, who I had missed so much—never got to go back to Jamaica to thank her before she passed for what she had done—and remembering the force of her love for me, which I didn't realize until then how much she was about love. I always thought that she was kind of always chastising me, but that day I realized that she was about love and wanted success for me.

And I went and just played free. And I said, "If I don't make it today, I'm already going to do it, I know I'm going to do it." I had the full force of confidence that I'm going to do it. And I just played and won the game. And so I got the GM norm and title with a round to spare.

K: Wow. I was getting Bell Hooks vibes with the all-about-love reference. But it's important to get a sense of who is in the corner, how you deal with certain moments, what you are consuming. And it did sound like the literature of greats who also had their challenges helped to move you along in some ways.

M: Absolutely.

K: And then also even sharing conversations with people who kind of get the journey in some respect but might not be going through it with you. I mean, you had Joshua Waitzkin, who was. But then to also have a mentor from the Black Bear School kind of talking you through that was certainly, I think, really helpful.

M: Yes, I think so. No person is an island, and we've got to lean on people in life. And that's okay. The ones who love us, the ones who get it, the ones who are not in it for anything but that they care about us. And then I firmly believe in the inspiration of our ancestors. All of us—whatever your background, I don't care what your race, what your creed, your ethnicity—whatever your background, everyone has had their journey. And there are a lot of ancestors who got us *all* to this point. And so I think we do ourselves a disservice if we don't lean on their strength, and what they dreamt of for us. They knew one day that we would be here.

You know, Dr. King's words, "I may not get there with you," right? "I may not get there with you." Those were big words when he said that: "I may not get there with you." And sadly, he didn't get to see all the fruits of his labor. But we each bear that responsibility from the legacy that brought us to this point.

And so I believe in being inspired, definitely, and from anywhere I can to be inspired. And being grateful for everything that has gotten me to this point.

K: Yeah. And in that spirit or in that vein, that kind of dovetails nicely with where I wanted to go next with respect to where we've been since 1999, frankly. 1999, you become the first and only African-American grandmaster in history. And no doubt that was a hugely momentous time, and now we're over 20 years later and you're still that guy. And the only guy.

And in some respects, there are many elements of your journey where even I can find some continuity with my journey. For instance, as far as resources, as far as pursuing it as you're older and really an adult. As far as some nudges along the way, hugely valuable to have—it would be fair to say a benefactor in that individual that supported your journey at the right moment when you were pushing as well.

And also, as far as how you actually started and developed your game: It was almost exclusively outside of the domain of really formal settings. That's ultimately the gift of your journey. But it's also, in some ways, one could say, a curse, to the extent that you maybe could have even been a much stronger player and much further than you ultimately got.

M: [smiling] Don't remind me! Don't remind me!

K: Oh, and so...

M: "I could've been a contender!" Absolutely.

K: And when you have that drive, that's certainly where things have the potential to go. Talking about equity and talking about within the context of Black History Month about access and opportunity, what do you think the needs are within our community, within the black chess-playing community at large, that ultimately will facilitate more talent coming through? I have a few ideas myself, but I'd love to hear your perspective there.

M: Well, it's funny. When I talk to my colleagues—and I'm talking big-time names, all right? I've been fortunate to have friendships with some of the best players in the world. So you talk about Garry Kasparov, Fabiano Caruana, Levon Aronian, Peter Svidler. I remember sitting at a dinner in Saint Louis and listening. We were all talking about our backgrounds, and Levon Aronian shocked me by saying that in formal schooling, he didn't pass third grade.

And I'm like, What do you mean? He said, "Yeah, I was a talented chess player and I was basically feeding my family. I was the breadwinner by third grade." That's what he was doing. And this is one of the most articulate, funny, personable guys, you know, and extremely well-read. So he continued his education, but not his formal education. But that's how young he started.

So then we went around the table, and it was the same people I just mentioned: Svidler, Fabiano, Garry, Leinier Dominguez; Alejandro Ramirez was there as well. So all these GMs who are top class, I will say, and I think only Garry finished college—and like [air quotes] finished college—because he was already a killer [at chess] when he was a young man, so he just had to do what he had to do for the university.

The rest of them, I think one graduated from high school. Everybody was studying chess. That was what they did. That was the resources that they had. Everything was being put into their chess studies for them to become elite players.

Now, to me: madness. Complete madness. I was 14 when I started. I was in high school. My mother couldn't afford a chess lesson. She didn't even want me even going to play chess. But she couldn't afford chess lessons, tournaments, all that. That was something that I had to basically do borrowing money from friends or any bit of allowance I got. Anything that I could do to be able to just have that little bit of scraps.

So to me, the chess challenge is the first thing: starting young, having help at a very young age, identifying talent—the talent has to be identified very early on—having that support early on, once you see that somebody has that talent, and then being able to bring the coaching, the intellectual resources of somebody like myself for example who has been through the fight, and anybody else we can bring in to come fight this struggle with us, so that young talented players don't have to go through what I went through, what you went through, on the path to trying to become a grandmaster. That requires a lot.

We have to understand that chess is still a rich person's game. That's just the facts. It's something that you need the resources for in order to go to the tournaments, hire the coaches, travel the world chasing norms… I mean, I didn't have a laptop until I was like 30. Just before I got my GM title. I was 31 when I finally owned a laptop or a computer of any kind. Resources matter.

When that child gets into it, who's the advisor… all those have to be in place before we can talk about people getting into that elite world of chess grandmastership. Of course, there are exceptions to that rule; I'm one, and I know of others as well, but if that's not in place, it's gonna always be an extremely difficult struggle.

K: Yeah, I totally agree. I think that the general chess-consuming audience doesn't quite understand or appreciate just the financial cost and investment that's required to get from Point A to Point B, particularly when historically over-the-board tournaments are not a source of revenue.

The idea is, essentially, if you're playing open tournaments in the US or even if you're fortunate enough to play some closed tournaments that happen in the US or other places abroad, you're paying for a hotel for 5-9 days. A FIDE-rated tournament is 5-9 days. For food for 5-9 days, airfare, and that's before having maybe some tools like a good computer, a coach who can give feedback… that's before those things even come into play. There's a massive overhead which you basically don't cover at all, even if you play at a reasonable level. The financial investment there is something that's massive, and talent can't necessarily overcome that, even if it exists. So that's just something to be extremely mindful of.

M: Absolutely. Talent and hard work, yes, and you have resources that take you to a point. But the fact is chess is a competitive game; your rating is not like climbing a mountain to a certain level—the mountain is fighting back. Your rating is relative to the people you are competing against, and if they have better resources, they're talented too, they're working hard too, you're up against it. And I'm not saying that you can't overcome it, but you're up against it. So the ecosystem that you're in matters a lot.

I was very fortunate to have the Black Bears School, but I can tell you that a lot of people who never had something like that—like you said, your strongest opposition was 1700-1800, and that's not gonna cut it for what your goals are when you're trying to become a 2500 or 2600 player. So the ecosystem you're in to be able to travel to those tournaments, eventually, I had to go abroad. Tournaments I played in Bermuda, in Bad Wiessee, Germany, where I got my second norm… I played in Lyon, in France… it was so damn cold, and I played so badly! But this was the little money I was saving up so that I could travel to these places.

And again, it wasn't until I got sponsorship and I was already a 30-year-old man with a child that I was able to really just pursue the game, and within 18-19 months, I got my last two norms. So it matters, and I think that's a very severe challenge for anyone who wants to become a strong player, that is for sure. Certainly, in our community, you have to marry the desire to get the title with the resources to be able to pursue it properly.

K: Yeah, absolutely. Desire and resources, they must be married together in some way, shape, or form.

Shifting gear somewhat, we've spoken about your chess background, your development, getting the title, some of the challenges that we're still facing today… I wanna actually talk about some chess stuff with you, just because you are a commentator, but ultimately still a chess player who has thoughts on the game and is thinking about working on the game and so on, so let's end with some commentary there. There are a few areas I wanted to go, and I'll basically just lay out a few of them, and you can choose to attack whichever one you want.

One is draws; personally, I've actually never really enjoyed them. I've never had a fondness for them; I've actually lost a lot of games, especially in the last ten years, just because I actively sought out a path that wouldn't eventually neutralize a game and head it toward even calmer waters. I've empathized with your public proclamations around how we need to address this in some way for chess to be more sporting.

There are all these openings where there are these fairly worked-out paths. We all know them well, the Berlin, Petrov, Queen's Gambit Declined… even sharper openings today, like the Grunfeld, have lines that go in this way.

M: That's an easy one! That's an easy one. I hate 'em. Draws suck. We should get rid of them. I would do it in a minute. But the reality is that it's part of the game, so you have to play the best moves. The only thing I would say on draws, and I think the most critical thing to say on draws, is don't keep them in your mind when you're playing the game. Play the position. But the position is also fair, and it will punish you if you try to pull blood from a stone, right? If it ain't there, you can't just make it happen.

You're playing an opponent as well, and they're skilled, they're dangerous… they will chop your head off if you go down a bad path. The draws that I don't like are the so-called "GM draws." That's the worst phrase possible! The GM draw? What is that? We're grandmasters, and you attach a statement like that…

Basically, the boring worked-out-before-the-game-draw where everyone knows you're not really playing each other, those are the ones I say are not legit. But the game is the game. Draws are within the window of accuracy, and if someone plays accurate chess against you and they don't make mistakes, or big enough mistakes to lose the game, you're not just gonna make them make a mistake. You're a part of that dance. They, too, are part of that dance. You have to respect the game itself and say, "Well, that's gonna be a draw." It's a draw, and you go on to the next game.

K: I contend, though, that structures change when the incentives change, and you have a system in place where frankly, even when you roll up into Candidates tournaments or qualifying for the highest titles, rating matters so much that top players in some respects may be incentivized in a way where not losing is actually more valuable than winning.

M: Good point.

K: How do you potentially evolve or change that dynamic in a structural way?

M: Okay, that's a different point and a good point to bring up. I love this point. To me, it's possible to get rid of draws by doing things like, for example, Norway Chess does, where there's an armageddon game after the first game. So there's a draw in the game? Now you play armageddon. Somebody has to win. I'm not a fan, per se, of this system, but I know people who really enjoy it. Fabiano Caruana, for example, has said that he likes that system, actually. So I think this is something you can embed.

One that I really wanna see get tried—it has been tried, I actually sponsored a tournament at the Marshall Chess Club to do it on a lower level, but it's never been done on a very high level—and I know this is a little bit on the wild side, is that if you play a classical game and it ends in a draw, you immediately turn the board around and whatever time is left on the clock, you start a new game. And then you just keep going. At some point, it's gonna get crazy; at some point, you'll have to give the player at least a minute, let's say, to play. But the game continues until somebody wins. That immediately makes sure the person who has White is not taking some clean draw because they're gonna get Black on the next game, and it's just going to keep going as such.

Alright, it's a fanciful idea, people have also thrown out the "three points for a win and one point for a draw" idea… there are different rules that you can put in place to incentivize winning, and I think that whichever one you choose is fine as long as it's reasonable and it's not a roll of the dice as such, as long as it's fair, then I totally believe that we can create systems that incentivize playing as opposed to just some tired-looking draw.

K: Gotcha! I think we just need to keep trying things, and ultimately that's one of the challenges that sometimes we do have. We're afraid to try things that are going to veer too far away from the traditionalist history of the game—which is valuable and matters—but as long as we keep trying various things, we will land on solutions like you're discussing.

M: Big point! Big point. The word you just said is "we." We, who? "We" means organizers. "We" means people with money. "We" means people who are sponsoring these events. And so it's not exactly like you and I will be like, "Well, we're just gonna do the tournament." I mean, to be fair, I did find a sponsor for the Millionaire Chess Open, and I did structure it in a way that you had to win in the last round in order to win the tournament.

I was able to do that for three years, and I think it worked. I mean, it worked well. We had excitement at the very end; you had to win. You had to play to win. There was a knock-out at the very end; the first part was a Swiss, and the finalists went on to a knock-out system. We're seeing that now on the Meltwater Tour, right? We're seeing that they do the same system. Swiss first, then you go to a knock-out at the end. I think that is the kind of thing we want to keep seeing. As long as sponsors are willing to have that mindset and put the money behind it, players will do whatever you tell them to! They'll play by any rules needed that you design, as long as there's money on the table at the end of it for them. I think that's all that matters right now in this space: sponsors and organizers have to decide that that's what they want to see.

K: Yeah, yeah, absolutely. I'm gonna end with a question about chess philosophy: You mentioned before that you had this tactical flair to your game, and that seems like it was somewhat imported from the Black Bear School in some way. For me, personally, I've always been a "war of attrition" guy; I believe you create a little weakness here, you create a little weakness somewhere else, the edifice will collapse. It's amazing that styles really do make fights in chess and that you can have so many different styles. What style do you think is more conducive to the metagame today? We have computers that have so greatly changed the way we think about and engage with the game; if you were playing with the same vigor you were some years ago, what would be the tactic you would take, given the tools at everyone's disposal today?

M: Me, when I look at it, I think my style would be controlled chaos. I think there's room, and this is something I'm working on right now—you might see it in a Chessable course soon...

K: Say that one more time?

M: I said you might see it in a Chessable course soon! I do have a Chessable course out there right now, The Secrets of Chess Geometry. I'm working on some different ideas that inspire me, and I think that there are complex ways to use the engine, the tools that we have now, which is Stockfish and friends, to prepare in a different kind of way than just what is the so-called "best move."

I think the fallacy of the best move holds a lot of people back. If you look at Stockfish or friends, you'll find that oftentimes there are three or four moves that are just equal in value. You could play any one of those moves. But one of those moves takes on a different nature. One of those moves takes on a different character. One is hyper-positional, solid, maybe a boring draw. Another one may be your war of attrition, "Maybe I can work this guy over." And then the other one is like, "That's a draw?! That's equal?! What are you talking about, that looks weird!"

To walk along that tightrope, as Mikhail Tal would say, you "...take your opponent to the dark forest where 2 + 2 = 5 and the path out is only wide enough for one of you." To me, that's where I would be. I would be finding those areas of chaos where it may be equal, but we gonna play. We gonna play chess.

I've seen some games go in that direction; I love those games when they go there. I remember Aronian defeated Dominguez recently in a game, and he said this was too hard for a human to work out over the board; it's equal, but I took him there. He knew he was taking him into a place where a lot of people just don't go. That's where the fun part would be for me, and I would hope that chess evolves into that kind of fighting spirit as opposed to the number-crunching that we see a lot, that just leads to equality in a lot of these classical games.

K: I totally agree with that. Chess is ultimately part art, part sport, part science. And I think it's up to you in some respect to work out what that ratio looks like. Your manner of describing what you would chart out, turning up the science in some ways or also creating a sporting element, and yeah… Good luck!

M: That's why I love Chess960 as well. I think that's bringing some of that sporting element into it, where we don't have perfect knowledge. We just have to fight with the tools at our disposal. That kind of trend, I really support; I want to see more chaos!

I know you said that was the last question, but I would like to make one point especially based on the topic being Black History Month. It's something that's really important to me. We've seen a lot of African American success in chess, not at the highest level that we want to see. You and your cohorts are trying to get to that next level, and I applaud that fight. But we haven't seen it with our girls, our African American girls and women. There's not been one African American woman or girl who's made the master title, despite over 100 males doing so.

For me, that is something that has become a passion, a cause that is near and dear to my heart. I'd like to see and support black girls' success in chess. We've had some who have come close: Rochelle Ballantyne, Darrian Robinson, Jessica Hyatt is now on the way, Baraka Shabazz back in the day. It's a shame that we don't see our sisters as powerfully so, and I think it's not just because of being African American, obviously. Like I said, over 100 males have done so.

But the fight for gender equality and gender parity as well, and being comfortable in a space like chess, which is similar to tech, similar to engineering, similar to the sciences, where women have not been as welcome or felt as welcome, we'll say. It's a different dynamic that I've come to try to learn to understand more recently, and they're combining the two challenges of race and gender. That's something I'm really pursuing at the moment, that's in my head constantly. I just wanna put that out there as something that's really important to me.

K: Well said. Jessica Hyatt, Darrian Robinson… there are folks that have been so close and are still close. I've been conversational with Jessica over the years and would really like to see her be next up. Anyway, we'll leave it at that! Maurice, thank you for sitting down and taking the time. It's been a pleasure, and onwards and upwards! Have a good February.

M: My young brother, I appreciate you, I applaud you, I support you, I can't wait to see the GM title next to your name. Let me tell you, I've been alone for 24 years now! It's crazy. When I became the first [African American GM], I said at the time when people were interviewing me that the beauty of being the first is that I know there's going to be a second and a third and a tenth as we rise in this game, and I'm still waiting. I'm still waiting, and I cannot wait to see that joyous day. So trust me, you have a fan. Thank you so much for having me.