First Verbalize, Then Analyze (Plus, One from the Rule Books)

I noticed two questions (posed by several readers) pertaining to my earlier article titled, “Finnish Defense & Tournament Prep.” Both questions are about an analysis I gave, and both are more than reasonable … on one level. Let’s take a look at the first one:

1.e4 d5 2.exd5 Qxd5 3.Nc3 Qe5+ 4.Be2 c6 5.Nf3 Qc7 6.d4 Bf5 7.0–0 e6

This is a line that Andrew Martin dubbed the “Patzer Variation”, and I dissed it with the apparently cryptic “8.d5!! black’s in serious trouble.”

In a way this was a setup since it was obvious to me that many readers would want to know why I was giving a critical central pawn away. On the other hand, the “Finnish” article wasn’t about detailed analysis, nor was it even about the Patzer Variation. Thus I set my trap and … this article was born from it!

In general, asking me to do more than a basic rundown on any opening is way beyond this column’s purpose. The problem is one of time: doing a deep analysis of any opening can take months, and trying to analyze a new move can take weeks of effort. For example, after I retired from active play I was looking at some sharp line in one of my favorite openings when I spied a very interesting Exchange sacrifice. I wasn’t sure it was completely sound, but I started exploring the position by putting in 1-3 hours a day for a few weeks. Suddenly it hit me: I don’t even play anymore, so what in the world am I doing? I stopped my analysis and that line is still a secret to this day.

When writing my new book (How to Reassess Your Chess 4th Edition) I found myself falling in love with quite a few positions. As a result, I would spend far too much time on them – as much as 3 days on one position in some cases (when you realize that I was analyzing hundreds of positions, you’ll begin to see why the book is so late!). The problem with this is not only lost time (which, when you equate it with potential earnings, doesn’t bode well), but also the stark reality that no matter how much analysis you do, a stickler for ultimate truth will find improvements (after spending weeks on one position) at some point in the future – it’s just unavoidable. Besides, do you really want to stare at endless variations, or would you prefer instructive prose mixed with simple but highly illustrative positions?

Now let’s return to our initial question: 1.e4 d5 2.exd5 Qxd5 3.Nc3 Qe5+ 4.Be2 c6 5.Nf3 Qc7 6.d4 Bf5 7.0–0 e6

Here White has quite a few good, solid moves to choose from, but I was hoping that curious readers of the column would think, “Hey, White is way ahead in development, and what do you want to do when you’re ahead in development AND the enemy King is still in the center? Crack it open! Play with as much energy as possible. So 8.d5 makes perfect sense in a philosophical sense, but does it actually work?”

This would have pleased me to no end. But no, the questions were always in the form of “What gives with 8.d5?”

I find this to be very unfortunate. So many players want to know if they can be masters someday (I think everyone of any age can reach the basic master/2200 level with dedication and work), but they haven’t even begun to learn the game’s ABCs. This same “I want it all right now” problem arises with calculation – they want to know how to calculate like a grandmaster, yet they don’t have an inkling about what’s going on in the position. Trust me when I tell you that calculation (or long streams of variations) usually won’t be too useful if you can’t verbally address the most basic points of a given position (that’s what my book How to Reassess Your Chess is all about).

Nevertheless, since the question has been raised, I will present a partial analysis that shows the kind of fun things that can occur after 8.d5. It’s in no way complete (dozens of pages can be written about the position after 8.d5), but if you want more you can spend many a fun day exploring all its secrets. I’ll also add that you should look at all this analysis from the point of view of the position’s basic needs: More development + black’s central King = CRACK IT OPEN!

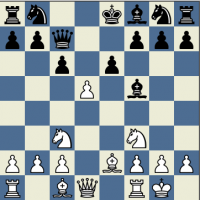

1.e4 d5 2.exd5 Qxd5 3.Nc3 Qe5+ 4.Be2 c6 5.Nf3 Qc7 6.d4 Bf5 7.0–0 e6 8.d5 exd5

Worse is 8…cxd5 9.Nb5 Qd8 10.Bf4 Na6 when 11.c4 cracks the position open even more (11.Nbd4 threatening both Bb5+ and Nxf5 is also promising). A sample: 11…Bc5 12.Qa4 Kf8 13.cxd5 exd5 (13…Qxd5 14.Ne5 gives White a powerful attack due to black’s horrible King and the threats of Rfd1 and Bf3. Note that 14…Qe4 loses to 15.Qxe4 Bxe4 16.Nd7+ Ke7 17.Nxc5 Nxc5 18.Bd6+) 14.Nbd4 (14.Rac1!?) 14…Be4 15.Bxa6 bxa6 16.Nc6 Qb6 17. Nfe5 and white’s attack is extremely strong.

9.Re1

Best, though 9.Nd4!? is also interesting.

9…Nd7 10.Bd3+ Be6 11.Nd4 0–0–0 12.Rxe6 fxe6 13.Nxe6 Qa5

13…Qe5 is probably best. After 14.Nxd8 Kxd8 15.g3 Ngf6 16.Bf4 Qh5 17.Be2 White is obviously better thanks to his two Bishops and black’s loose King, but I’m not sure just what the exact assessment should be.

14.Bd2!!

The obvious 14.Nxd8 isn’t as good.

14…Re8

14…Ngf6 15.Nb5 (15. a3!?) 15…Qb6 (15…Bb4 16.Nd6+ Kb8 17.Bf4) 16.Be3 Nc5 17.Bf5 Rd7 (17…Nfd7 18.b4! continues to fan the flames) 18.Nxf8! Rxf8 19.a4 cxb5 (on 19…a5 White has both 20.Qd4 and 20.c3! intending b2-b4) 20.b4 Qc7 21.Bxc5 has to be crushing.

15.Nb5 Qb6 16.Be3 c5

16…Qa5 17.Nbc7.

17.Nxf8! Rxf8

17…Nxf8 18.Bf5+ Ne6 19.Qxd5 Nf6 (19…Qxb5 20.Bxe6+ Kb8 21.Bd7 wins) 20.Qc4 when Black’s in terrible shape since 20…a6 21.Nd4 is quite unpleasant.

18.b4! Ngf6

Also possible are:

1) 18…Nh6 19.bxc5 Nxc5 20.Qh5 (eyeing the possibility of Qh3+) 20…a6 21.Rb1! and the attack is too strong

2) 18…a6 19.bxc5 Nxc5 20.Qg4+ Qe6 21.Qxg7 is winning for White.

19.a4 Qe6 20.Bf5! Qe5 21.Bxc5 and White is all over his opponent.

Some (more advanced) players will find the tactics in this analysis interesting, players of any strength might find it entertaining, while others might be horrified by all of this. I think you’d agree that the short explanation (White is sacrificing a pawn so he can open lines of attack against the enemy King) is preferable and more illuminating. And it’s that short explanation that all of you should strive to be able to answer for yourselves. Again: first verbalize, then analyze!

The other question (regarding the position after 1.e4 d5 2.exd5 Qxd5 3.Nc3 Qa5 4.d4 c6 5.Bd2 Qc7 6.Nf3 Bg4 7.h3 Bh5 8.g4 Bg6 9.h4 h5 10.Ne5 Bh7 11.Qf3 e6 12.g5 Bf5) has the exact same philosophical base: White has a large lead in development and wants to put some serious heat on Black as quickly as possible (if White plays quietly, Black will have a chance to get more pieces out and to move his King away from the center). My recommendation of 13.g6 makes sense if you see it as a way of opening new lines of attack. Of course, it also gives away a pawn, and that (combined with no analytical follow-up) threw some readers. But my (silent) message was more or less the same as the previous one: white’s ahead in development, he wants to attack, and 13.g6 begins the “ripping open” process. However, there was another very strong move:

13.Bd3

Obvious and strong.

13…Bxd3

13…Nd7 14.Bxf5 Nxe5 (or 14…exf5 15.Nxf7 Kxf7 16.Qxf5+ Ke8 17.Bf4 Qb6 18.0–0–0 with a crushing attack, as should be obvious after 18…Kd8 19.Rhe1 when white’s pieces are primed to explode, while most of black’s are still sitting at home) 15.dxe5 exf5 (15…Qxe5+?? 16.Be4 wins) 16.Qxf5 with an extra pawn for White.

14.cxd3

Threatening both 15.g6 and 15.Bf4.

14…g6

No better is 14…Bd6 15.Nc4 Nd7 16.Ne4 Be7 17.Bf4 and Black will be squashed.

15.Bf4 Qb6

15…Bd6 16.Ne4 is just one more nightmare scenario for Black.

16.Nc4 Qd8 17.Ne4 and the position speaks for itself.

So why did I recommend 13.g6 when the far simpler 13.Bd3 is so good? Well, I only wanted to give one move so I chose the more melodramatic and instructive 13.g6 which illustrates the “open lines at all costs” idea far better than 13.Bd3 does.

Here’s what can happen after the recommended pawn sacrifice:

13.g6 fxg6

Also bad is 13…Bxg6 14.Nxg6 fxg6 15.Ne4 with an enormous plus since 15…Qf7 16.Qxf7+ Kxf7 17.Ng5+ Ke8 (17…Kf6 18.Rh3 threatening both Rf3+ and Re3 is game over) 18.Nxe6 Bd6 19.0–0–0 and white’s winning due to his two raging Bishops, black’s vulnerable King, white’s lead in development, etc.

14.Bd3 Ne7 15.Bf4 Qd8 16.Bxf5 gxf5 17.Qg3 and black’s busted due to his holes on g5 and g6, his lack of development, and threats along the h2-b8 diagonal. For example: 17…Qxd4 18.Rd1 Qb4 19.Nd3 and White wins the b8-Knight and the game.

Ultimately one wants to be able to break down any position into its logical components and also to calculate quickly and deeply. However, where calculation is a hard thing to master (and it doesn’t really tell you much about a position from a human perspective … imagine someone asking you what’s going on and you answering, “White is 0.28 better because of 28.Bh4 a6 29.Rfe1 b5 30.c3 Bb7 31.Ne5” … Pardon?), reading the board and giving yourself a solid understanding of what’s going on (by the verbalization of both side’s imbalances) is very much in every player’s range (with some training, of course), and very much to every player’s benefit.

Althanatos asked:

If you are about to promote a pawn, but want to make a Rook instead of a Queen (the Queen would lead to a stalemate), and if you reach to the side for a Rook but grab a Queen instead, do you have to promote to a Queen or can you put it down and promote to a Rook?

Dear Althanatos:

Finally an easy one! However, it’s also one that I’m sure many won’t know the answer to.

Quoting from the Official Rules:

10H. Piece touched off the board. “There is no penalty for touching a piece that is off the board. A player who advances a pawn to the last rank and then touches a piece off the board is not obligated to promote the pawn to the piece touched until that piece has been released on the promotion square.”

Mr. Althanatos, this reminds me of a habit I had during my salad years as a player. After a few trades had occurred, I would invariably reach over, take a captured pawn, and flip it over and over between my thumb and forefinger (it would calm me, while the rhythmic motion of the pawn would hypnotize my opponent). At no time did anyone tell me I had to move the pawn!

An interesting aside (or a random trip down memory lane): While visiting a very successful screenwriter (the screenwriter, one of my closest friends, tragically died young), I was contentedly chatting away and flipping a pen (the flipping thing became a habit that I carried away from the board!) when an actor friend of his stopped by. The actor was doing research for a big gangster role and, upon seeing my pen flipping, said, “That’s perfect! It’s perfect!” He then asked permission if he could use that same affectation for his character. I gave him a crash course on pen flipping (showing him how the flipped pen could instantly be shoved through some poor victim’s throat) and off he went to practice and master it.

The moral of that story ... Okay, there’s wasn’t any moral (other than pawn flipping can eventually lead one to develop a whole new martial art). As I said, it was a trip down memory lane. At my age, when you think of something from the past you just run with it!