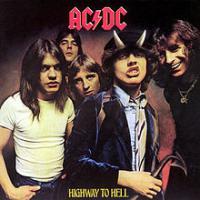

Highway to Chess Hell

CP said: “This game was played a few weeks ago, at a strong tournament in which I played up into the Open section. I was playing with the black pieces and lost the game after a five-hour struggle that went past 1 AM – to date the longest game I have ever played. I hope you find it interesting and I thank you for spending your time reading this.”

Mikeal Davis (2010) vs. Calvin Parnon (1824), 2011

1.c4 Nf6 2.g3 c6 3.Nf3 d5 4.Bg2

This is a very popular position on the international stage, with a myriad of famous grandmasters playing both sides. Where it will end up is still a mystery, since White can play d2-d4 and enter a Closed or Open Catalan, or White can avoid d2-d4 altogether and keep the game in English or Reti territories.

4…dxc4

CP said: “I was somewhat nervous heading in, as I know close to no theory at all for playing these types of positions.”

Very common, though 4…Bg4, 4…g6, and 4…e6 are also typical replies. Black’s most popular move is 4…Bf5 intending …e6, …Be7, …0-0, …h6, etc. when he would enjoy a sound, extremely solid position.

1.Nf3 Nf6 2.g3 d5 3.Bg2 c6 4.0-0 (4.b3 Bf5 5.c4 e6 6.0-0 Be7 7.Bb2 h6 8.d3 0-0 9.Nbd2 Bh7 10.a3 Nbd7 11.b4 a5 12.Qb3 axb4 13.axb4 Qb6 14.Bc3 Rfc8 15.Qb2 Bf8 16.h3 Qd8 17.Ra5 Rxa5 18.bxa5 b6 19.axb6 Qxb6 20.Ra1 Qxb2 21.Bxb2 Bb4 22.cxd5 cxd5 23.Rc1, 1/2, O. Panno (2585) – A. Karpov (2660), Madrid 1973) 4…Bf5 5.d3 e6 6.c4 dxc4 7.dxc4 Qxd1 8.Rxd1 Nbd7 9.Nc3 h6 10.h3 Bc2 11.Re1 Bh7 12.Be3 Bb4 13.Rec1 0-0 14.Na4 Be7 15.Nd2 Rfd8 16.Nb3 Be4 17.Na5 Bxg2 18.Kxg2 Rab8 19.a3 Rdc8 20.b4 b6 21.Nb3 c5 22.bxc5 bxc5 23.Rab1 Rc6 24.Bf4 Rbc8 25.Nc3 Ra6 26.Nb5 Ra4 27.Nd2 g5 28.Be3 a6 29.Nc3 Rxa3 30.Nde4 Rc7 31.Nd2 Ne8 32.Rc2 Nd6 33.g4 Bf6 34.Nce4 Nxe4 35.Nxe4 Be5 36.Rd2 Kg7 37.Rbd1 Nf6 38.Nd6 Rb3 39.Ra2 Rb6 40.Rad2 Rcc6, 0-1, V. Korchnoi (2650) – A. Karpov (2705), Tilburg 1986.

White often avoids black’s hoped for setup by answering 4…Bf5 with 5.cxd5 cxd5 6.Qb3 when 6…Qb6 is considered best. It might look like White is better after 7.Qxb6 axb6 (or that Black will be bored to death), but these positions are rich enough that the stronger player can get the best of his opponent from either side.

1.c4 Nf6 2.g3 c6 3.Bg2 d5 4.Nf3 Bf5 5.cxd5 cxd5 6.Qb3 Qb6 7.Qxb6 axb6 8.Nc3 Nc6 9.Nb5 (9.d3 e6 10.Nb5 Kd7 [10…Bb4+ 11.Bd2 Ke7 12.Nfd4 Bxd2+ 13.Kxd2 Bg6 14.f4 h6 15.a3 Rhc8 16.Rac1 Bh7 17.Bh3 Nd7 18.Rc3 Nxd4 19.Nxd4 Rxc3 20.Kxc3 Rc8+ 21.Kd2 Bg8 22.Rc1 Rxc1 23.Kxc1 f6 24.Kd2 Bf7 25.Bg2 g6 26.Nb5 Nb8 27.e4 dxe4 28.Bxe4 Nc6 29.Kc3 e5 30.fxe5 fxe5 31.a4 Kd7 32.Na3 g5 33.Nc4 Bxc4 34.Kxc4 Kd6 35.Kb5 Kc7 36.Bxc6 bxc6+ 37.Ka6 g4 38.b3 c5 39.Kb5 Kb7 40.a5 bxa5 41.Kxc5, 1-0, L. Portisch – V. Smyslov, Wijk aan Zee 1972.] 11.Nfd4 Bg6 12.f4 Bc5 13.Be3 h5 14.h3 Rhc8 15.a3 Ne8 16.Kf2 Nd6 17.Rac1 Nxb5 18.Nxb5 Ra5 19.Bxc5 Rxb5 20.Be3 Rxb2 21.Rb1 Ra2 22.Rxb6 Bxd3 23.Rxb7+ Rc7 24.Rxc7+ Kxc7 25.Bf3 g6 26.g4 d4 27.Bc1 Bxe2 28.Bxe2 d3 29.gxh5 Rxe2+ 30.Kf3 Nd4+ 31.Kg4 Rg2+, 0-1, L. Pantsulaia (2510) – M. Kobalia (2614), Internet Blitz, 2005.) 9…Kd7 10.0-0 e6 11.d3 Be7 12.Be3 Bc5 13.Nbd4 Nxd4 14.Bxd4 Rhc8 15.a3 Bg4 16.Bc3 Bd6 17.h3 Bh5 18.g4 Bg6 19.Rac1 Ke8 20.Nh4 Rc6 21.Nf3 h6 22.Nh4 Rcc8 23.Rfe1 Kd7 24.e4 e5 25.Nf5 Bxf5 26.exf5 Ra4 27.Bd2 Rc6 28.Bf1 Ra8 29.Be3 Rac8 30.Rxc6 bxc6 31.d4 Re8 32.Rd1 b5 33.Kg2 exd4 34.Bxd4 Be5 35.f3 Bxd4 36.Rxd4 Re1 37.a4 Rb1 38.Rb4 bxa4 39.Bd3 c5 40.Rb6 Kc7 41.Rb5 Rc1 42.f4 Nd7 43.f6 Nxf6 44.g5 hxg5 45.fxg5 Nd7 46.h4 g6 47.Ra5 Ne5, 0-1, A. Mazara (2274) – J. Ehlvest (2591), Santo Domingo 2010.

White’s tried just about everything here too, with 5.0-0 being the most popular move, and 5.Qc2, 5.a4, and 5.Na3 also being given some attention by various bigwigs.

5…g6

So far, we’re still swimming in the theoretical sea, though black’s most popular choice is 5…Nbd7 with the position after 6.Qc2 Nb6 7.a4 a5 8.Na3 Be6 9.Ng5 Bg4 proving to be a very interesting battleground.

6.a4

This prevents …b7-b5, but many players ignore black’s …b5 idea and dare him to do it with 6.Na3 (which I feel is stronger than 6.a4). Then Black has to decide whether to let White recapture his c-pawn by Nxc4, or to hold onto it by 6…b5. Here’s a sample of what might occur:

6.Na3 b5 7.Ne5 Qc7 8.d4 a6 9.b3 cxb3 10.Qxb3 Be6 11.Qc2 Bg7 12.Bf4 Nh5 13.Nxg6 Nxf4 14.Nxf4 Bxd4 15.Rad1 Bf6 16.Nxe6 fxe6 17.Qb3 Kf7 18.Bh3 Qe5 19.Rd3 c5 20.Re3 c4 21.Nxc4 bxc4 22.Qb7 Qb5 23.Bxe6+ Kg7 24.Qe4 Nc6 25.Bd7 Rad8 26.Bxc6 Qc5 27.Qg4+ Kf8 28.Be4 h5 29.Qg6 h4 30.Rc1 hxg3 31.hxg3 Rd4 32.Kg2 Qh5 33.Qxh5 Rxh5 34.Bb7 Ra5 35.Rc2 Rd7 36.Bc8 Rc7 37.Be6 c3 38.f4 Rb5 39.Bb3 Rb4 40.Re6 a5 41.Ra6 Rc5 42.Ra8+ Kg7 43.Kf3 Rd4 44.e4 a4 45.Rxa4 Rd3+ 46.Kg4 Bd4 47.Ra8 Rd2 48.Rg8+ Kh7 49.Rxd2 cxd2 50.Rd8 e5 51.fxe5 Bxe5 52.Rxd2 Rc3 53.Kf5 Bxg3 54.Rd7+ Kh6 55.e5 Rf3+ 56.Kg4 Rc3 57.e6 Re3 58.Bc2, 1-0, E. Pigusov (2520) – A. Graf (2415), Pavlodar 1987.

6…Bg7

CP said: “At this point I thought that a fianchetto structure would make the most sense for me in the position, so that I could bring my bishop to e6 and also possibly put pressure along the h8-a1 diagonal.”

7.Na3 a5?!

CP said: “I didn’t think that the strange position arising from 7...Be6 8.Ng5 Bd5 9.e4 h6 10.exd5 hxg5 was a reasonable option, so I decided to give the pawn back with the idea of planting a knight on b4.”

All this has been seen, including 7…Be6, which is (along with 7…Qd5) Black’s most critical try. Since the sequence you gave starting with 8.Ng5 hasn’t scored very well for White, best is probably 8.Qc2 Qd5 and now 9.h4 is the only try for advantage, though 9…Qe4! throws a spanner into the works. After 10.d3 cxd3 11.exd3 Qb4 it remains to be seen whether White has enough compensation for the sacrificed pawn.

8.Nxc4

White has an edge here – the Knight on c4 is very well placed, the b6-square is weakened and needs Black to keep an eye on it, and White has two center pawns to black’s one (of course, Black can make use of the hole on b4, and his overall position is very solid). If Black wants to play this line, he really should embrace 7…Be6.

8…Na6 9.d4

White’s still a little better after this (the position now resembles a sort of Grunfeld Defense), but 9.d3 (defending the Knight and covering the e4-square) is more accurate: 9…0-0 10.Bd2 Nb4 11.Bxb4 axb4 12.Qb3 c5 13.d4 cxd4 14.Rfd1 Qd5 15.Qxb4 Ra6 16.Nb6 Qe6 17.Nxc8 Rxc8 18.Nxd4 Qb6 19.Qxb6 Rxb6 20.Nb5 h5 21.Rac1 Rb8 22.b3 Ne8 23.Rd7 e6 24.e3 Be5 25.Rc5 Bd6 26.Nxd6 Rxd6 27.Rxd6 Nxd6 28.Rc7 Kf8 29.Rd7, 1-0, F. Molina (2246) – I. Efimov (2491), Cortina d’Ampezzo 2004.

9…Be6

CP said: “Now I was starting to feel somewhat confident, as my pieces are well positioned and aimed at white’s holes on the queenside and I don’t have any clear positional problems.”

10.Nce5?

The Knight was very happy on c4 (hits a5 and b6) so obeying Black and moving it is a major concession.

The right way to handle this position is 10.Qb3! (yes, the Queen is stepping on the e6-Bishop’s diagonal, but Black isn’t able to make use of that fact). Now 11.Qxb7 is an obvious threat (when …Bxc4 Qxc6+ wouldn’t make Black happy), but white’s real idea is to follow with Ng5: 10.Qb3 0-0 11.Ng5 Bxc4 12.Qxc4 when his two Bishops guarantee him a plus.

10…h6?

There’s no reason to play a passive move like this. Instead, 10…Bd5 centralizes the Bishop and promises Black a fine game. Take note: you wasted a tempo to stop a perceived threat, but instead you could have used that tempo to place your Bishop on a dominant square. One move is purely defensive and also weakens your kingside structure a bit, while the other makes new gains.

11.Re1

I’m not a fan of this move either. White intends e2-e4, but this will leave both d4 and e4 in need of defense and Black, in classic Grunfeld style, will do his best to pressure them.

11…0-0 12.e4 Nb4 13.Bd2 Qb6

CP said: “My pressure on white’s position is clear and I think I stand better. However, I don’t see where my opponent made a mistake as all of his moves seem normal. Perhaps 6.a4 wasn’t accurate?”

Hopefully my earlier comments have answered these questions for you.

I don’t know if you’re better here (seems evenly balanced to me), but I very much like your confidence and “the cup’s half full” mentality.

14.Bc3 Rfd8 15.h3 Ne8?!

CP said: “White is almost forced to play h3 to prevent …Ng4, and now instead of playing the logical continuation …Nd7 after which white is in trouble, I choose an overly complicated plan and waste time.”

White’s in trouble after 15…Nd7? I admit that Black has the initiative and is putting serious pressure on white’s center, but that’s how these “you get a big pawn center and I’ll attack it” games go. After 15…Nd7 16.Nd3 Bc4 17.Nxb4 axb4 18.Bd2 e5 19.Qc1 Be6 20.dxe5 Kh7 (20…Nxe5 21.Nxe5 Bxe5 22.Bxh6 Qd4 23.Re2, =) 21.Be3 Qc7 22.Re2 Nxe5 23.Nxe5 Qxe5 24.f4 and the same “you get a big pawn center and I’ll attack it” philosophy is still in effect, with more or less equal chances.

16.Qe2

Since you intend to start a battle against c4 (as stated in your next note), why doesn’t White just play 16.b3 and end that “battle” before it begins? I guess White didn’t like the d8-Rook staring down his Queen on the d-file, but I don’t see how Black can take advantage of that particular game of chicken.

16…Nd6

CP said: “There is a battle being fought over the c4-square, but white has adequate resources to defend it.”

17.Red1 Bb3 18.Rdc1 Qa6

CP said: “At this point I wasn’t sure how I could increase the pressure on my opponent’s position, as despite my pieces being much better placed than his there are no tactics available that I could see and I don’t have a good way to bring my last rook into the action. I thought that maybe I could attempt to trade off white’s queen as it defends some key squares, but this didn’t bring much because white can defend everything with his tempo moves Bf1 and Nd2.”

I don’t think your pieces are “much better placed than his”, though they are well placed. But it’s always nice to see a guy that loves his position and is doing everything he can to push his agenda in his opponent’s face. I should add that 18…Qa6 seems very logical, and I can’t see anything better.

19.Qxa6 Rxa6 20.Nd2 Be6 21.Bf1?

A tempting move, but I don’t care for it. First off, the c4-square isn’t a problem anymore, all the more so if White plays the correct 21.b3! (stops …Na2 nonsense and clamps down on c4). Second, black’s Rook isn’t particularly happy on a6, so why should White force it to move to a better square? And finally, white’s light-squared Bishop was doing a good job defending e4 and also (at some point) preparing a possible d4-d5 push.

21…Raa8 22.f4 Kh7

CP said: “Due to my pressure on the queenside, white’s pieces are in passive and defensive positions so I thought that I would be able to break white’s center with …f5.”

Note how Black is trying to make something happen with every move. The …f7-f5 advance will ultimately give his pieces access to the d5-square. Good or bad, right or wrong, his mindset is fantastic!

23.Kg2?

White’s been completely outclassed in this game. Black’s moves are more logical and more pointed than anything White has done. 23.Kg2 shows that White just doesn’t know what to do – he’s become confused and is bobbing up and down in the ocean of black’s ideas.

White needed to fight back with 23.g4 f5 (23…Na2!?) 24.exf5 gxf5 25.Bxb4 axb4 26.Bd3 Kg8 27.Ndf3 and now 27…Ra5 (going after the a4-pawn) 28.Kf2 Rda8 29.Re1 leads to a dynamically balanced position (29…Rxa4? 30.Rxa4 Rxa4 31.Nxc6!). Instead of 27…Ra5, better (and far more interesting) is 27…fxg4 28.hxg4 Rf8 29.Ng6 Bxg4 30.Nfe5 Rfe8 31.Nxg4 (31.d5!?) 31…Bxd4+ 32.Kh1! Bxb2?? (32…h5! 33.N4e5 Bxb2 34.Rg1 Bxa1 35.Nh4+ Kf8 36.Nhg6+ with a draw by perpetual check) 33.Rg1 Bxa1?? (Black had to play 33…Kg7) and now White wins by force:

23…f6?

CP said: “I thought that as the knight is white’s most active piece in its position on e5, it would help my position to kick it away from its post before breaking with f5. In reality, the knight stands far better on c4 where it menaces a5 and I should have played f5 directly.”

A logical, honest appraisal. White’s Knight does indeed stand very well on c4, so forcing it to go there wasn’t a very good decision. But this just shows how compelling the old, “I’m attacking your piece with a pawn” dictate can be. When attacking something, you somehow feel safe and in control for that brief moment, until he moves away from your one move threat and reality hits you on the head. Clearly, attacking an enemy piece is only worthwhile if it leads to some certain gain, or chases his piece to a worse square. The act of attacking/threatening has no virtues by itself.

Black should have gone ahead with his plan to conquer d5 by 23…f5 (much stronger than the tactical 23…Nxe4) when 24.exf5 Nxf5 is clearly better for Black (who owns the d5-square and is threatening d4).

24.Nec4 f5

This doesn’t have the same punch as it did a move ago. Instead, 24…Nxe4 is interesting: 25.Nxe4 Bd5 26.Re1! Nc2 27.Nb6 Nxa1 28.Nxd5 Nc2 29.Re2 cxd5 30.Nc5 Nb4 31.Rxe7 b6 32.Ne6 Rg8 offers roughly equal chances.

25.Nxd6?

Not so hot. I would prefer 25.e5, entombing the g7-Bishop (at least for a while) when white’s space advantage (and the dead g7-Bishop) trumps black’s control over d5 (I prefer White).

25…exd6

CP said: “I think this is a fatal error on my part. Now white establishes a protected passer in the center.”

Black gives this move a question mark, but I think it’s the best move in the position! The alternative, 25…Rxd6, leads to the same kind of position as given in the previous note – white’s better after 25…Rxd6 26.e5 Rdd8 27.Nc4.

Regarding white’s protected passed pawn, amateurs fear them, but experienced players know that they are way overhyped. In fact, in How to Reassess Your Chess, 4th Edition, I show that protected passed pawns are sometimes a bad thing! The main point, though, is to remove the fear of protected passed pawns so you can judge them cleanly, depending on the particular position.

26.e5 dxe5 27.dxe5 Nd3

This effectively gives up a tempo since the Knight has to hop right back to c5. It’s a shame, because for most of the game Black made sure all his moves had a clear purpose (other than some mindless threat), but moves like 23…f6 (a really bad move) and 27…Nd3 (not great, but not the end of the world) undermined most of his earlier fine play and, more importantly, set the tone for self-doubt and, ultimately, psychological collapse (you can usually recover from sub-par moves, but you can’t recover from mental collapse).

Instead of attacking windmills, Black should have optimized his pieces by 27…Bf8 (it was dead on g7, but it’s active here) 28.Nf3 Bb3 when I slightly prefer black’s position (the passed e-pawn isn’t going anywhere). For example, 29.Bc4 (29.Nd4 Bd5+ 30.Kh2 Bc5) 29…Bxc4 30.Bxb4 Bxb4 31.Rxc4 Rd3.

28.Rd1 Nc5

CP said: “I no longer have enough pieces to put adequate pressure on white’s position and my endgame is losing due to my weak pawn on a5 and white’s protected passer on e5.”

What a difference a couple moves make! We saw Black crowing about his chances a short time ago (which I loved), but now his depression has colored everything in a dark, “I’m doomed” tint. When you get into this kind of funk, you are more than likely to make moves that fulfill your doomsday viewpoint.

29.Nc4??

White goes berserk! A tightening move like 29.Be2 would have been more productive, though black’s still fine after 29…Bf8.

29…Nb3??

CP said: “A bad response to a bad move, after which white can just convert the position. I missed the simple 29...Rxd1 30.Rxd1 Nxa4 after which black can possibly hold a draw.”

This is where Black actually tosses the game. But what really blows my mind is his comment that after the obvious 29…Rxd1 30.Rxd1 Nxa4 – “after which Black can possibly hold a draw.”

Wow! He’s so freaked out about the passed e-pawn (which is doing nothing and going nowhere) that even after White throws away material, he still thinks black’s in trouble. As I said, once you embrace doom, it’s hard to crawl out of the pit. The fact is, after 31.Ra1 Bd5+ 32.Kf2 b5 33.Nd6 Nxc3 34.bxc3 Bf8 the only player begging for a draw (with no guarantee that he’ll get it) is White.

Of course, the guy that was playing Black earlier in the game would have instantly seen 29…Rxd1 30.Rxd1 Nxa4. But the “new” guy that’s playing Black now missed it because he was no longer looking at the board in a positive manner – he (subconsciously) “knew” he was doomed and he was hell bent on proving it!

30.Rab1 Bd5+ 31.Kh2 Be4 32.Rxd8 Rxd8 33.Re1 Nd4

CP said: “At this point, my opponent was in severe time pressure and I was trying to somehow force a blunder as he only had a few minutes remaining for seven moves.”

A sentence I’ve heard a million times (I’ve even said it myself) – oh so common, but oh so wrong, wrong, wrong. The best way to induce a blunder is to Play the Best Moves! Once again, Black needed to get his dead dark-squared Bishop into the game by 33…Bf8 (though he’s still lost).

34.Bg2 Bxg2 35.Kxg2 b5 36.axb5 cxb5 37.Nd6 Nc2 38.Re2 b4 39.e6!

Black was so sure this passed pawn would end up killing him that I would have bet money that he would eventually find a way to make it happen. And, sure enough…

39…bxc3 40.e7, 1-0.

Chess can be so cruel. Black had all the ideas, and for much of the game just seemed like a far superior player than his higher rated opponent. Then, for whatever reason, he lost faith in his position and took a direct highway to chess hell. Once again, we see just how important psychology is in a game of chess.

Lessons From This Game

* A positive attitude is worth a couple hundred rating points.

* As Black demonstrated for much of this game, even a non-master can push advanced agendas and make use of logical plans.

* Once you embrace doom, it’s hard to crawl out of the pit.

* In chess, the player that makes the best moves and comes up with the best plans often doesn’t win. As the old saying goes: “The winner is the player who makes the next to last mistake.”