How to Evaluate Chess Positions (Example)

Give1take2 asked:

My question in a nutshell is, “How do you evaluate a position?” How would you decide in a game between two moves that both look good? How do you find which one would be more beneficial to your position even though they look the same? My standard so far has been that after finishing a game and analyzing it with a program, I try to see where I could have chosen a better move (even in games I have won) by looking at the program's choice. Is there like a manual that professionals like yourself go through before choosing a move, because I’ve noticed after analysis that I’ve lost games to titled players even though I would be doing better initially by a score of +1.5 or sometimes even +2.

Dear Give1take2:

Correct evaluations can be very hard, or very easy, depending on each particular position. Some rely on pure calculation/tactics, and others call for a very advanced ability to see beyond the usual rules of positional chess. However, most of the time basic but solid evaluations can be constructed by making use of my system of chess imbalances.

The idea is that the vast majority of players don’t have anything to grasp onto while looking at a position. Most just start to calculate (the old, “I go there and he goes there …”), but they don’t have any idea what the position itself is calling for. Let’s face it, if you don’t know what the position’s needs are, how are you going to know which moves to calculate, or even if calculation is necessary?

Because every non-master student I’ve ever had was pretty much at a loss when it came to reading the board’s priorities, I devised a simple, easy to learn methodology for players in the 1400 to 2100 rating range. When I first did this (about 25 years ago), a lot of people laughed at me and thought it was garbage (critics always ridicule anything that’s new). However, the decades have been kind to me and this “imbalance system” is now used by many chess teachers (even grandmasters use it to teach!). In fact, the idea of imbalances has become a normal part of chess nomenclature! My latest book (How to Reassess Your Chess, 4th Edition – Chess Mastery Through Chess Imbalances) leaps into every aspect of imbalances (and chess psychology!) in unprecedented detail (it’s a 672 page, life-changing positional study course).

Here’s my list of imbalances: Superior minor piece, Pawn structure, Space, Material, Control of a key file, Control of a hole/weak square, Lead in development, Initiative (though in the book, I usually refer to it as “Pushing Your Own Agenda”), King safety, and Statics vs. Dynamics.

The book teaches you what each imbalance is, shows you its importance and its positives and negatives, and illustrates how to use a combination of all the imbalances to come up with a logical plan, or a logical series of moves, or simply one logical move. Often, no calculation is required to understand the soul of a position.

Let’s look at two examples:

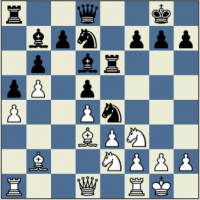

This seems like a complex position, and there are all sorts of moves that appear to be reasonable. On top of that, since Topalov is White one might expect some sort of aggression since he’s one of the most dynamic players in the world. However, calculation won’t get the job done because you don’t know what the position’s goals are. Note that I said, “the position’s goals”, not YOUR goals. That’s because you usually have to do the position’s bidding, and the only way you can do that is if you learn to read the “body language of the board”. How can you read the board? What’s in this position that the amateur can grasp onto? By listing all the imbalances for both sides BEFORE you look for a move, that hidden “ah ha” moment can be uncovered! This is how I “read” the position after 14…a5:

* White has an advantage in queenside space.

* Black has a potentially weak pawn on c7.

* If Black pushes the c7-pawn to c6 or c5, bxc6 will leave Black with a weak pawn on b6 and a hole on b5.

* Black’s d5-pawn is weak since it can’t be defended by another pawn.

* Black’s only source of counterplay is on the kingside – his d6-Bishop, e6-Rook, e4-Knight, and Queen are all eyeing that area.

* Black’s b7-Bishop, which is defending d5, is playing a purely defensive role.

* Black’s dark-squared Bishop is giving firm support to the c7-pawn while also playing a key role in any kingside attack that he might drum up.

* White’s b2-Bishop is inactive.

NOW you have something to grasp onto. Since c7 is on an open file, it’s white’s main target (the book goes deeply into a state of mind called “Target Consciousness”, but that’s another imbalance related topic for another time). Unfortunately, it’s solidly defended by that d6-Bishop (which is also aiming at white’s King!). Also, your own dark-squared Bishop on b2 is garbage. Hmm … his dark-squared Bishop is god, yours is garbage. Doesn’t that suggest a move? And, suddenly, you should know exactly what needs to be done (and all the other “reasonable” looking moves flutter away):

1.Ba3! forces the exchange of white’s worst piece for black’s critically important Bishop on d6. No calculation was needed here. Instead, a solid (but basic) understanding of the general position made the correct move obvious. Here’s the rest of the game:

1…Rc8 2.Bxd6 cxd6

Of course, 2…Rxd6 was possible, but then c7 would be a permanent source of concern. After 2…cxd6 that’s no longer the case. In addition, the e5-square is also covered (ending all Nf3-e5-c6 ideas). Of course, 2…cxd6 comes with its own baggage: the d5-pawn is weak and will need babysitting for the rest of the game.

3.Rc1 Ndf6 4.h3

Topalov (New In Chess 4, 2007) now said: “As you can see, all this is not about concrete lines, but about clear positional weaknesses. I knew that it didn’t matter how long it would take me, but in the end all the Rooks would be exchanged, further highlighting his structural problems.”

Topalov, one of the greatest attacking players in the world, is making it clear that his course in this game isn’t dependent on his personal tastes (i.e., attack), but rather on the dictates of the board (a quiet buildup in accordance with the imbalances).

4…Re7 5.Qb3 h6 6.Rxc8 Qxc8 7.Rc1 Rc7 8.Rxc7 Qxc7 9.Qc2

Topalov had this to say in regard to the position that would result after the exchange of Queens: “I can chase away the Knight on e4, transfer my Bishop to b3 and sooner or later I will exert pressure with two pieces on d5 and push my kingside pawns.”

Okay, there’s no getting around it—this is clearly a plan! But did he use any strange “system” (or deep calculation) to create it? No, this too is based on the imbalances: he will chase away black’s advanced Knight by f2-f3 (Knights need advanced squares to be effective—thus he intends to turn a good enemy piece into a passive one), he’ll aim his pieces against the weakness on d5, and then he’ll gain space on the kingside by advancing his pawns there (which would give him yet another positive imbalance to work with).

9…Qe7 10.Qc1

White’s Queen already controls the c-file, but now it also defends e3. This shows white’s intention to chase black’s one active piece away with an eventual f2-f3 (when the e3-pawn will be happy to have some support).

10…g6 11.Nh2 Kg7 12.h4

This gains kingside space, deprives the e4-Knight of the g5-square, and threatens to win by f3.

12…Ne8 13.f3 N4f6 14.Nf1 h5 15.Nf4 Nd7 16.Qe1 Nf8 17.Qg3 Kh6 18.Nxh5!?

18.Kf2 followed by Nf1-d2-b1-c3 would have continued the grind and maintained the pressure. However, Topalov decides to up the ante in his opponent’s time pressure. Can Black find all the right defensive moves with his clock rapidly ticking down to nothing?

The rest of the game, which has nothing to do with our theme (tactics suddenly take over), is given with minimum comments:

18…gxh5 (18…Kxh5?? 19.Qf4 wins outright) 19.Qg8 f5 (The only move) 20.Ng3 Ng7 21.Bxf5 Ng6 22.Bxg6 Kxg6 23.Nxh5! Qxe3+ 24.Kh2 Qe7?? (Black cracks in time trouble and plays the losing move. Correct was 24…Qxd4 when a draw would be the most likely outcome) 25.Nf4+ Kf6 26.g4 Qf7 27.Qd8+ Qe7 28.Qg8 Qf7 29.Qd8+ Qe7 30.Qxe7+ (30.Qxb6 was even stronger) 30...Kxe7 31.Kg3 Ne6 32.Nxe6 Kxe6 33.f4 Bc8 34.f5+ Kf7 35.h5 Bd7 36.h6 Kg8 37.Kf4 Be8 38.Kg5 Kf7 39.h7 Kg7 40.h8=Q+ Kxh8 41.Kf6 Bxb5 42.Ke7 Bd3 43.f6 Bg6 44.f7 Bxf7 45.Kxf7, 1-0.

Mr. Give1take2, you asked how you would decide between two moves that look good, but in the game we just looked at, there were all sorts of moves that looked good. Thus the answer is to break the position down by imbalances and, more often than you might imagine, the right move will suddenly be obvious.

This same imbalance mentality can also help you find a move that’s anything but obvious. Our next example shows this to perfection.

Black has two things going for him: better pawn structure and that nice Bishop on b7. Everything else that’s sweet about the position belongs to White:

* His Rooks dominate the only open file and also eye both c7 and f7.

* White’s Queen is in the black King’s face.

* Except for black’s threat of …Bc8 (which would force White to play Re7 – not the end of the world, but not what White wants), he’s pretty much helpless.

* Black’s kingside dark-squares are like Swiss cheese.

* So White’s advantages are based on Dynamics (more active pieces, pressure against black’s King, threatening Queen), while black’s game is based on Statics (pawn structure). I have a huge chapter in my book titled, Statics vs. Dynamics. In general, statics promise a long term plus, while dynamics call for more immediate, forceful measures.

What all this tells us is that White has every right to look for a knockout punch, and that punch will almost certainly take place on the kingside. Two moves that suggest themselves are 1.Ng5, which simply threatens to end the game with Rxf7. Unfortunately, 1…Qxg2+ is a good reply. Another logical try is 1.Rf4 (again threatening Rxf7), but 1…Qxd7 would make White want to poke his own eyes out with a stick.

If we continue to ponder the situation, we will remember that black’s kingside dark-squares are very weak. Ah, if only we had a dark-squared Bishop on d2! Then 1.Bh6 would just mate the guy. However, we don’t have a dark-squared Bishop. And so we’re left asking, can anything else make use of that dark-square highway to black’s King? And, once you latch onto that idea, it might strike you that there is indeed a piece that can do that!

1.Kf4!!

The King thinks it’s a Bishop, and heads for h6 as quickly as it can. Incredibly, there’s absolutely nothing Black can do about this.

1…Bc8

I’m going after your Bishop!

2.Kg5

I’m going after your King!

1-0. It’s mate after 2…Bxd7 3.Kh6, while 2…Kh7 3.Qxg6+ (3.Rxf7+ also does the trick) 3…Kh8 4.Qh6+ Kg8 5.Kf6 leads to another dark-squared mate.

Hopefully this will give you a taste of what you can accomplish if you study my imbalance system. It takes some work to fully master it, but once you do you’ll find that you’ve become a far stronger player. On top of that, when you look at master games, you’ll suddenly see all sorts of subtle things that you never previously noticed, thereby making chess as a whole a far more engaging pursuit.

Finally, a word about computers. Computers show you moves that they, the machine, would play. At times those moves are human, and at other times they are alien. However, you’re not a computer, and the moves you need to find are human. Using a computer to tell you what you should have done is an iffy idea because, though it might show you the right move, it doesn’t explain the ideas about WHY the move is right. Thus, other than giving you tactical insight, it’s not going to improve your understanding of chess at all.

Of course, one should mix a solid understanding of the imbalances with tactical training, endgame acumen, and opening study (though imbalances are an integral part of opening study too!).