Identical Twins: the KIA and the London System

Here is a game I played in a G/60 tournament on 9/24/11. This game is the third of a four round tournament. Both my opponent and I have one point and need to win to have a chance of doing something in the fourth round. I am playing white.

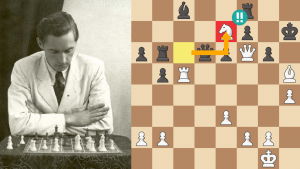

Maurice Maynard (1528) vs. Alexandra Botez (2014)

1.d4 g6 2.Nf3

Here or on the next move White should play e2-e4 and take the whole center. Reasons to do so: 1) The Colle and white’s 2.Nf3 followed by 3.Bf4 London System just doesn’t work against black’s move order; 2) If your opponent wants to hand you the world, take it! Learn a line against the Pirc and employ it whenever your opponent gives you the green light to do so.

2…Bg7 3.Bf4

I like the system you are trying to use, but it doesn’t have any bite against this move order. Instead, you should play 3.e4 and go into a Pirc/Robatsch, or 3.c4 and seek to enter a King’s Indian or Grunfeld. Personally I would play 3.e4 here.

3…d6 4.h3 Nd7

The London System (1.d4 followed by Nf3 and Bf4, though sometimes Nf3 is held back a bit and an earlier Bf4 occurs) often turns into the Black side of the King’s Indian Attack vs. the French, though with an extra tempo for White. This allows the dark-squared Bishop to get outside the pawn chain (to f4), which significantly adds to white’s chances. When playing a “reversed opening”, it’s critical that you fully master the ideas of the Black/tempo down version.

Let’s have a look at both the Black version of the KIA and the “reversed” White version. That way we can understand why many players as White (versus the French) use it, and why players as White enjoy the reversed version (White taking the “French” side with a tempo more).

THE KIA VERSUS THE FRENCH

THE “CHARMS” OF THE REVERSED KIA

COMMON TRAPS IN THE REVERSED KIA/LONDON SYSTEM

5.e3 e5

Mr. Maynard said: “This is the first time I have seen this move playing the London.”

The “London System” (also dubbed “The Boring Opening” about 25 years ago in some theoretical article) isn’t particularly effective if black’s Knight hasn’t landed on f6 yet. The reason is that Black can easily get …e7-e5 in and then place the kingside Knight on e7. That setup has scored extremely well for Black.

6.Bh2 exd4 7.exd4 Ne7

8.Bd3

In the game Kai Wesseln (2365) – D. Lau (2230), Oberliga Nord 1997, White tried the more active 8.Bc4, but Black was fine after 8…0-0 9.0-0 Nb6 10.Bb3 Bd7 11.c3 Nf5 12.Nbd2 Bc6.

8…0-0 9.0-0 Nb6

Eyeing the c4-square. The game M. Kozak (2285) – M. Vokac (2455), Czech Republic 1996 saw 9…Nf6 10.Nbd2 Bf5 11.Bxf5 Nxf5 with a good game for Black.

10.c3 h6

Mr. Maynard said: “I thought this move weakened the kingside.”

It’s not the end of the world. Black intends to play …Be6, grabbing hold of the light-squared. Her …h6 stops the e6-Bishop from being bothered by a White Knight via Ng5. Of course, White can eventually play c3-c4, grabbing hold of d5, but then d4 is weakened with the result that black’s g7-Bishop would gain significantly in strength.

Though that’s all a bit convoluted, I appreciate black’s thinking regarding light-square domination. However, 10…Bf5 is both obvious and equal.

11.Nbd2 Be6 12.Qc2 c5??

Perhaps Black is an aggressive player, or perhaps she’s playing aggressively due to the huge rating difference, but this move (which is very well-intentioned) seems to be a bit much. Instead, she could have retained a more or less equal game by 12…Re8 or 12…Qd7.

The main problem with 12…c5 is that it turns white’s h2-Bishop, which was hitting granite when black’s pawn stood on c7, into a fire-breathing dragon on the now-loosened diagonal.

13.dxc5 dxc5 14.Rfe1 Nbd5 15.Rad1

Mr. Maynard said: “Bringing my rooks to open files to get something going.”

White’s Rooks are gunning down the two central files, while black’s are still sitting at home. White’s Bishops are also doing a better job than their black counterparts – white’s h2-Bishop in particular is eating through the board on the h2-b8 diagonal.

White’s Knights also have some serious potential, with the f3-Knight being able to take up house on e5, and the d2-Knight being able to effect serious penetration via Nd2-c4/e4-d6.

15...Qc8 16.Ne5

An excellent move, though 16.Ne4 eyeing c5 and d6 might be even stronger.

16…a6 17.Ndf3

Mr. Maynard said: “Bringing my pieces to the center, she’s pushing pawns on the queenside.”

17...b5 18.Qe2

Mr. Maynard said: “Making room for my bishop on b1 or c2.”

18...Nc7

19.b3?

Mr. Maynard said: “I wanted to take on f7 or g6 with the knight but could not figure it out so b3.”

Your whole army was primed and ready for action, so you should have something. In fact, the undefended Knight on e7 and the potentially loose Bishop on e6 scream for tactics. To make matters worse, you saw the ideas against f7 and g6 but chickened out with the defensive 19.b3, which leaves c3 vulnerable and, more importantly, gives Black a free move.

Since you mentioned both f7 and g6, let’s look at what happens if you drop a bomb on either square:

19...Ned5 20.Rc1?

Mr. Maynard said: “Defending c3 and places rook opposite queen.”

On move 19 you had the chance to throw for a couple game winning touchdowns, but instead, with 19.b3, you tried to run and ended up losing 5 yards. Now you’re justifying this Rook move, which turns an active Rook on the open d-file into a passive babysitter for the pawn on c3. In other words, you’re still better, but you just lost another five yards. Instead of this rather sad move, 20.Qd2 retained an enormous amount of pressure against the enemy position (20…Rd8 21.Nc6 Bxc3?

20...Re8 21.c4 bxc4 22.Nxc4?

Mr. Maynard said: “Threatening to play Nd6.”

This is a very natural move, but 22.bxc4!, depriving black’s pieces of the important d5-square, is much stronger:

22...Bxh3

Mr. Maynard said: “Shock and panic. Have I blown another game?”

Shock and panic indeed! You should have anticipated this possibility when you moved your Knight off the e-file with 22.Nxc4 (after all, his e8-Rook is staring right at your Queen). If you had time, you should quietly ponder the situation and not move until you get a firm grip on the realities of the position. However, when someone is low on time and has to face this kind of surprise, hysteria is a frequent visitor to players of all levels.

Probably 22…Bf5 was a tad better than 22...Bxh3, but 22…Bxh3 has more shock value.

23.Qd2?

Another in a series of meek moves (19.b3, 22.Nxc4, and now 23.Qd2). Correct was 23.Nfe5! (threatening both 24.gxf3 and 24.Nd6) 23…Bxe5 24.Nxe5 Bf5 25.Rxc5 Bxd3 26.Qxd3 Qf5 27.Qxf5 gxf5 28.Rd1 Rac8 29.g4! (ending back rank problems with gain of time) 29…Ne7 30.Nd7 and black’s lost.

Note the difference between your move and the recommended one: 23.Qd2 is a purely defensive move, while 23.Nfe5 blocks the threat of …Rxe2 by bringing the f3-Knight into the battle. 23.Qd2 is passive, 23.Nfe5 is dynamic and continues to push white’s agenda.

23…Rxe1+ 24.Rxe1

24…Qg4?

Tempting, but wrong. The simple 24…Be6 puts Black right back in the game.

25.Bf1 Bc3 26.Qxh6

Mr. Maynard said: “Getting my queen close to her king and eyeing the bishop on h3.”

26...Bxe1 27.Nxe1 Re8 28.Nf3

28.Nd3!? also looks very strong.

28…Bxg2 29.Bxg2 Ne6 30.Nce5 Qh5 31.Qxh5

31…gxh5

Mr. Maynard said: “At this point we both had about 80 seconds left. I thought about offering a draw but did not think she would accept.”

Two things about the draw offer: 1) You are winning, so Black would have been wise to accept the draw. On the other hand, you're winning, so why offer a draw? 2) There’s such a thing as a psychological draw offer. This means that you might fully expect the offer to be refused, but you also know that your opponent will take extra time thinking about it. Thus the offer is actually a ploy to entice the opponent to dither away some extra thinking time.

32.Nd7?

32.Nxf7! gives White a winning position.

32…f5??

The solid 32…Kg7, though much better for White, allows Black to keep on fighting.

33.Nf6+??

33.Nfe5 was very strong since Bxd5 is threatened, and if Black moves the d5-Knight to safety, then 34.Nf6+ ends things. Thus, after 33.Nfe5 Nec7 34.Nxc5 white’s two Bishops for a Rook should lead to an easy win.

33…Nxf6 Low on time and not paying attention I blunder my knight. I play on for a few more moves but there is not enough time to even think of a defense and I resign.

~ Lessons From This Game ~

* Playing the same opening moves against anything your opponent throws at you rarely works. Though you might be in love with a safe but not particularly critical system (things like the Colle or Reversed Stonewall or lines like 1.d4 followed by Bf4), black choices like 1…g6 or 1...b6 often demand a change of plan from White. Fortunately, that change of heart usually means White building a big center via d4 and e4 and going for the gusto.

* When I switched from 1.e4 to 1.d4, I did it because I got sick of mainline Sicilians and nasty French Defenses. However, I didn’t switch due to 1.e4 g6 or 1.e4 d6. Thus, when my opponents answered my 1.d4 with either …g6 or …d6, I would (as a matter of principle) play 2.e4 and take the whole center (which Black so kindly allowed me to do). Players that use 1.d4 followed by Nf3 sideline systems should do the same – toss out 2.e4 if Black allows you to do it!

* The London System (1.d4 followed by Nf3 and Bf4, though sometimes Nf3 is held back a bit and an earlier Bf4 occurs) often turns into the Black side of the King’s Indian Attack vs. the French, though with an extra tempo for White. This allows the dark-squared Bishop to get outside the pawn chain (to f4), which significantly adds to white’s chances. When playing a “reversed opening”, it’s critical that you fully master the ideas of the Black/tempo down version.

* There’s such a thing as a psychological draw offer. This means that you might fully expect the offer to be refused, but you also know that you’re opponent will take extra time thinking about it. Thus the offer is actually a ploy to entice the opponent to dither away some extra thinking time.