My Favorite Classic Games, Part 9

This series is all about the classic games that, as a young teen (15 years of age), affected me in a profound manner. In general, they were positional games since, for a kid that grew up on attacking chess and combinations (12 to 14 years of age), strategic considerations were left behind and, as a result, were alien.

Thus, when I was finished studying games by Anderssen, Morphy, Spielmann, Marshall, Alekhine and Tal, I decided to check out less extreme players and broaden my chess horizons.

The games I will share might or might not be masterpieces; the criterion for this series is that they taught me an extremely important lesson(s) that made me well rounded and much stronger. I’m hoping that these games will teach you the same lessons, thereby improving your positional understanding and helping you become a better player.

In part 6 of this series, we looked at the Carl Schlechter vs. Walter John masterpiece, which is one of the most amazing examples of massive spatial annexation I’ve ever seen. It’s a game I looked at many times as a child and, as the years inexorably rolled by, I continued to look at it with my students.

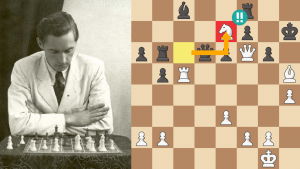

However, there’s another famous space game, played in 1929 by Capablanca that, though not quite as fine as the Schlechter game, also makes the eyes pop open in awe.

Here’s a comic example of total helplessness, created by massive space gains.

This position seems like a joke. Black’s rooks, light-squared bishop, and b8-knight can’t move without suffering serious material loss. The f6-knight can’t move due to Rxg5.

The only pieces that can move without dropping the house are the king, queen, and the f6-bishop, which back and forth between e7 and f6. To make matters worse, White threatens Nxg5 and there is nothing Black can do about it.

Why did Black resign? Play around with this final position and see if you can figure out why Black was delighted to give up and walk away from this nightmare situation.

Of course, space on one side is often negated by the opponent having space on the other wing. In that case, it’s space vs. space, and the winner is often the first to break through or the first to create other advantages for his or her side.

chess "space" via astronomy.fm

LESSONS I LEARNED FROM THESE GAMES:

- The side with more space should try and avoid too many exchanges.

- The idea of “cat and mouse” is to do in 10 what you can do in 1. Why? When the opponent is helpless, making various useless moves will tire him, and when you begin the correct plan, he will be too confused and exhausted to notice what’s happening.

- Just moving your pieces to center squares won’t get the job done against a strong player. You need to find a way to get active pieces or come up with some kind of strategic goal, and then move your pieces to the squares that will make those things a reality.

- To repeat, space on one side is often negated by the opponent having space on the other wing. In that case, it’s space vs. space, and the winner is often the first to break through or the first to create other advantages for his or her side.

RELATED STUDY MATERIAL

- Read IM Silman's previous article: My Favorite Classic Games, Part 8

- Watch IM David Pruess' video on how to exploit a space advantage.

- Take a lesson on space in the Chess Mentor.

- Solve some puzzles in the Tactics Trainer.

- Looking for articles with deeper analysis? Try our magazine: The Master's Bulletin.