The Greatest Chess Player of All time - Part I

By Jeff Sonas

With Garry Kasparov announcing his retirement last month, it seems like an appropriate time to look back on his career and compare it with the careers of other all-time greats, to try to place him in some kind of historical context. The obvious question at this point is: was Garry Kasparov the most dominant chess player of all time? And if not, who was?

Of course, there is no clear answer; it is a question that can be interpreted many different ways, and most of the answers are extremely subjective. First of all, I am not trying to produce any sort of definitive statement about whose actual chess skill was greatest, or strongest, or most artistic. I'm not looking at the moves they made; I am only looking at overall game outcomes (win, lose, or draw), and drawing conclusions from analysis of those outcomes. I have developed several different "metrics" for exploring this issue objectively, and I would like to share some of them with you. It’s an entertaining topic, and even if you think the question is ultimately meaningless, I hope that you will nevertheless enjoy the ride.

I have invented a new rating formula, and a new way to calculate performance ratings, and a new way to evaluate the "category" of historical tournaments. I have calculated monthly historical ratings going all the way back to 1843, and so I can tell you in great detail who was the highest-ranked at any time and for how long (according to my formulas and my underlying data). I hope that these inventions can help to shed additional light on some of the more intriguing "best-ever" questions that surround chess but have always required a somewhat subjective answer.

However, I do want to say one quick thing about rating formulas. In recent months, I have read quotes from many different people saying that we need a new rating system, that the FIDE formula is too conservative and slow, and that right now the top-rated players can simply remain inactive and retain their valuable high ratings at no cost to themselves. My rating formula was carefully chosen to be more accurate and dynamic than the FIDE rating formula, and to require players to stay quite active in order to maintain high ratings.

There are many ways to measure "greatness" or "dominance" in chess, even when you are just looking at things statistically. You can look at world championship results, or win/loss records, or performance ratings (if you have historical rating lists). Or you can look at peak ratings, or world rankings, or the gap between players’ ratings (if you have historical rating lists).

"If you have historical rating lists"... it sounds so simple. But it used to be that we couldn’t really use many of those metrics across a significantly long stretch of chess history. We all knew the lineage of world champions, and we had ratings for everyone going back a few decades. But if you wanted to look earlier, there were no real rating lists to speak of, other than Professor Elo’s book that only provided one peak rating per each player’s entire career. Then came Chessmetrics...

Who was ranked #1 for the longest consecutive span of years, or for the most combined years over their entire career? Not just since the 1970's, but going all the way back to the mid-nineteenth century? Who had the strongest single tournament performance, or the strongest single match performance? Who was the highest-rated player of all time? Who had the most success in super-tournaments, or the largest rating gap between #1 and #2 at one time? All of these are very valid questions when you’re trying to figure out who was most dominant, and it’s not like it was the same player winning each of these categories.

There are so many different approaches that I can’t do them all justice in merely one article, so I have turned this into a four-part series. In the remainder of Part I, we will look at Wilhelm Steinitz and Emanuel Lasker, the first two world champions. In Part II we will look at some more recent all-time greats, especially Bobby Fischer and Anatoly Karpov, and Part III will cover some of Garry Kasparov’s most impressive accomplishments. Finally in Part IV I will introduce a brand-new way of looking at this topic, as well as wrapping up with some final thoughts.

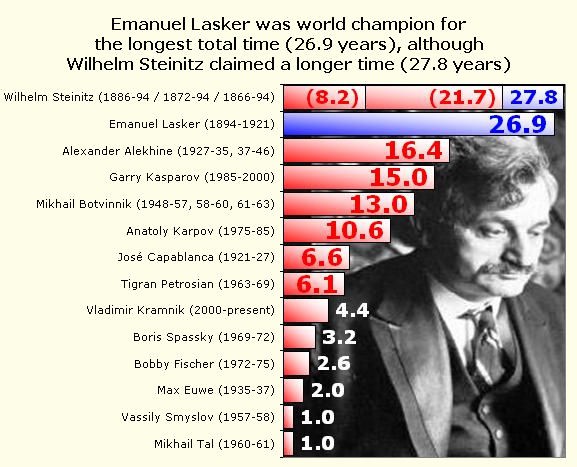

Before we get into the Chessmetrics numbers, however, I would like to start with the most traditional approach to assessing historical dominance: looking at the duration of each world champion’s reign. This is a somewhat controversial topic, for a number of reasons. First of all, World War I and World War II are considered to have artificially extended the reigns of Emanuel Lasker and Alexander Alekhine, or at least to have postponed the rightful challenges of José Capablanca and Mikhail Botvinnik (among others). Second, there is considerable disagreement regarding exactly when Wilhelm Steinitz originally became the first World Champion. Various claims have been made for his term as champion having started with his match against Adolf Anderssen in 1866, or his first match against Johannes Zukertort in 1872. There is no question, however, that once Steinitz won his second match against Zukertort in 1886, that he was definitely world champion. So depending on whom you ask, Steinitz was either champion for 8.2, 21.7, or 27.8 years, until losing the title to Emanuel Lasker in 1894. Historians appear to have mostly settled upon 8.2 as the "official" duration of Steinitz’s reign, but of course there will always be disagreement about that. In any event, if you try to graph the total amount of years that each player spent as champion, this is what you get:

Until now, this is mostly where the analysis had to stop, or at least it had to slow way down. However, now that we have reasonable (though not perfect!) historical rating lists, on a monthly basis, we can start to describe other measures of dominance. Certainly one method that comes to mind, when we talk about "dominance", is to measure how far the rating-point-gap was between the #1 and #2 players, and to see, for each player, what their maximum gap achieved was, when they were ranked #1.

Garry Kasparov recently stated that "the greatest gap between the number one and the rest was Bobby Fischer in 1972". This would be very revealing, if true, because you would think that the largest rating gap would have occurred long ago, when there were relatively few players within striking distance of the strongest player. Now, you have to be careful in trusting these mid-nineteenth-century ratings too much, because on some dates there is only a small handful of players with enough games to qualify for the rating lists, and one or two aberrant performances can totally upset the list. If you have an approach that is sensitive enough to thrust Paul Morphy into the #1 spot after a tiny number of rated games in the late 1850's, it will probably thrust others as well into an unfamiliar limelight, names like Serafino Dubois, Lionel Kieseritzky, and Berthold Suhle. Subjectively we can just dismiss them as outliers, or even flaws in the rating approach, but they come along for the ride on any real attempt at an objective approach.

So, what do the numbers say about "the greatest gap between the number one and the rest"? Was Garry Kasparov right? Well, sort of...

Wilhelm Steinitz, the first official world champion, dominated the 1870's. He had the longest winning streak in the history of master play, winning 25 straight games over a nine-year period between 1873 and 1882 (although he didn't play at all between 1876 and 1882). Already #1 in the world going into the Vienna tournament in 1873, Steinitz won his final 14 games, and then both games in the playoff against Joseph H. Blackburne. Thirty straight months of inactivity caused Steinitz's Chessmetrics rating to drop 70 points but he was still #1 when he faced Blackburne, the #2 player in the world, in a match in February/March of 1876. Incredibly, Steinitz maintained his winning streak, by winning all seven games of the match. This was an incredible feat, and a performance rating more than 50 points higher than anything ever seen in chess to that point. On the next monthly Chessmetrics ratings list, on April 1st of 1876, Blackburne had dropped down to #4 in the world, and Steinitz was rated 199 points higher than the new #2 player, Henry Bird. This is easily the largest gap between #1 and #2 achieved by any top-rated player over the past century and a half:

As a historical aside, a match between the #1 and #2 players in the world is actually quite rare, sort of the Halley's Comet of chess. It has only happened fourteen times in history, more than half of them including Anatoly Karpov! Before historical ratings, it would have been easy to think that matches between #1 and #2 regularly happened every three years, because that's in fact how we defined #1 and #2, as being the winner and loser of the latest world championship match. However, the rating lists reveal that the chess world once had to wait 41 years between any matches involving the top two players from the rating lists, stretching from Steinitz-Zukertort II in 1886, all the way until Alekhine-Capablanca in 1927. And after that match, it was even worse, with a 47-year dry spell until the Karpov-Korchnoi Candidates' Final in 1974. Note that the Lasker-Capablanca match in 1921 didn't count because Lasker, the world champion, had fallen off the rating list due to inactivity. Of course Steinitz himself was also quite inactive in the mid-to-late 1870's, playing only the Blackburne match between 1873 and 1882 (at which point Steinitz continued his winning streak at another Vienna tournament in 1882, with a first round defeat of... Blackburne!). So if you discount the 1870's as just being too aberrant, then you can see from the above chart that Bobby Fischer did indeed have the largest rating gap of modern times. So I guess the winner of this category is half-Steinitz and half-Fischer.

Rather than just focusing on one peak date, if you look across players' entire careers, there is a significant amount of statistical evidence to support the claim that Emanuel Lasker was, in fact, the most dominant player of all time. In this latest Chessmetrics effort, I did work a lot on improving my formula, but I also did a lot of manual work collecting 19th century results, trying to focus on collecting all known complete events rather than just a hodge-podge of available games.

One of the things that surprised me most, when I actually calculated the 19th-century ratings, was how early Lasker showed up as the top-rated player in the world. I had always thought that it would have been around the time he took the official title from Steinitz in 1894, but in fact Lasker entrenched himself at the top of the list at the tender age of 21, in the summer of 1890, and did not give up the #1 spot until well after the turn of the century. And although Lasker did lose the world championship to Capablanca in 1921, Lasker's victory a few years later at the 1924 New York tournament was enough to move him back to the top-rated spot for two more years after that. So even though he was world champion for 27 years, his time at the top of the rating list actually stretches an additional four or five years in either direction. On the other hand, he was not a particularly active champion, and so there are several points where inactivity or a rare poor showing would drag his Chessmetrics rating down to the point that someone else surpassed him. Nevertheless, over the course of his career, Lasker spent 292 different months on the top of the rating list, a total of 24.3 years, more than anyone else in history. Garry Kasparov might have caught Lasker if he had stayed around a few more years, but he ended up second all-time, with a total of 21.9 years. The following chart makes for an interesting companion piece to the first graph about world champion durations:

Tigran Petrosian, with the eighth-longest reign of all time among world champions, isn't even in the top fifteen when you rank players according to the number of months spent as the #1-rated player. And of course you can see that both Bobby Fischer and Garry Kasparov had shorter spans as world champion than the rating lists would have suggested. Fischer was the top-rated player in the world for much of Petrosian's reign and all of Boris Spassky's. Despite being world champion until 1969, Petrosian never retook the top spot on the Chessmetrics rating lists after Fischer moved into the #1 spot with a perfect score at the U.S. Championships right at the end of 1963. And of course we all know that Kasparov continued to have the top rating in the world even after losing the world championship to Vladimir Kramnik in 2000. Some people will certainly say that the actual world championship title is all that matters, but I think it must be preferable to have both perspectives.

You might have noticed that in none of this analysis did I actually tell you what the players' actual historical rating numbers were. It's a tricky point. I think most people would agree that historical ratings are very meaningful in identifying the relative strength, at one particular time, for contemporaries of each other. It's the effort of trying to compare ratings across eras that is less popular. Even if that important point has always led you to discount the usefulness of historical ratings, I hope you will agree with me that there are approaches you can take, such as the last two graphs indicate, which do let you make comparisons of relative dominance across the years, without having to compare actual ratings or calibrate two rating lists against each other.

However, if you do concede the point that it is possible to assign meaningful numbers that allow direct comparison of ratings across eras (even if the numbers represent the relative degree to which individuals dominated their own time, rather than making any claims about whose chess was objectively stronger), it opens a whole lot of analytical doors. You can talk about who was the highest-rated player of all time, and about performance ratings, which can be applied to lots of different situations.

I even have my own follow-up to the recently-announced Chess Oscars (for which the top players of each year are identified, based upon subjective balloting). I'm sure you won't be surprised if I tell you that I have developed my own technique for retroactively determining who deserved the "gold medal" each year, with a method that is somewhat more objective. I even have another new graph to illustrate that particular measure of dominance. Now, more objective is not necessarily better, but it hopefully does allow for a wider perspective than you would otherwise have. However, you'll have to be patient and wait a while for all of those things I just talked about, because this article is getting quite long.