The Right Way to Study an Opening

Mr. Schell said: "Last weekend I played in the 40th Annual Queen of Hearts tournament in Montgomery, Alabama. I found the atmosphere overwhelmingly friendly and competitive. In the interests of full disclosure, I withdrew after the third round because I felt some of my schoolwork required more attention than I had given it. I heartily endorse the 41st annual Queen of Hearts tournament! I am including for your review my second round loss."

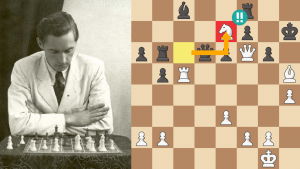

Inman (2145) - Schell (1848), C10, Alabama 2012 (TC: 90/30 sudden death, 5 second delay)

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 dxe4 4.Nxe4 Bd7

Schell said: “I have employed this system in the past with hopes to draw stronger opponents.”

Nowadays fans of the French Defense have all sorts of strange ways to drag opponents into strange vistas: 1.e4 e6 2.d5 d5 3.Nc3 h6 (I don’t understand this move, but quite a few strong players have given it a shot); 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nd2 h6 (I still don’t understand it); 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.e5 Ng8 (this I DO understand!); 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.e5 Bf8 (really strange, but it reaches the exact same position as 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.e5 Ng8!).

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 dxe4 is hardly strange. In fact, it’s a popular way to keep complications down while striving for a solid, very sound position. One cool thing about it is that black’s preparation time is cut in half since 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 dxe4 4.Nxe4 and 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nd2 dxe4 4.Nxe4 leads to the same position! No more agony trying to figure out how to deal with 3.Nd2!

What’s the point of 4…Bd7? Black intends to place his light-squared Bishop on the very active c6-square, followed by …Nbd7, …Ngf6, …Be7, and …0-0. Sounds simple! Here’s the first game I could find with this system:

J. Corzo – J.R. Capablanca [C10], Havana 1902

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 dxe4 4.Nxe4 Bd7 5.Nf3 Bc6 6.Bd3 Nd7 7.0-0 Ngf6 8.Bg5 Be7 9.Nxf6+ Bxf6 10.Be3 0-0 11.c3 b6 12.Qc2 Kh8 13.Nd2 Re8 14.Bxh7 g6 15.Bxg6 fxg6 16.Qxg6 Qe7 17.f4 Qh7 18.Qxh7+ Kxh7 19.Nf3 Rg8 20.Rae1 Rg6 21.Bd2 Bd5 22.b3 Rf8 23.Kh1 c5 24.dxc5 Nxc5 25.c4 Ba8 26.Bb4 Rfg8 27.Bxc5 Rxg2 28.Be3 Bh4 29.Rd1 Bf2 30.Rd7+ Kh6 31.Rd5 Bxe3 32.Ng5 R2xg5 33.fxg5+ Rxg5 34.Rf6+ Kh5 35.Rxe6 Bxd5+ 36.cxd5 Rg1 mate. The 14-year-old Capablanca made it look easy. Is this system really that good? Read on!

5.Nf3 Bc6 6.Bd3 Nd7 7.O-O Ngf6 8.Qe2

This move let’s Black swap off to a drawish position.

8.Nxf6+ has a bit more bite: 8…Qxf6 (8…Nxf6 9.c3 Bxf3 10.Qxf3 c6 is also common) 9.Be2 Bxf3 10.Bxf3 c6 – with the usual space and two Bishops for White, while Black has a solid position and will strive to trade off a pair of Bishops by …Bd6-f4 with a manageable Bishop vs. Knight battle.

White’s most challenging moves are 8.Ng3, 8.Ned2, and 8.Ng5.

8.Ng3 Be7 9.b3 Bxf3 10.Qxf3 c6 11.Bb2 Qa5 (11…0-0 12.c4 Re8 13.Rad1 Bf8 14.Rfe1 Qa5 15.Bb1 Rad8 16.h4 Ba3 17.Ba1 Bd6 18.Re3 Qc7 19.Ne4 Bf4 20.Re2 Nxe4 21.Rxe4 Bh6 22.d5 cxd5 23.cxd5 exd5 24.Rxe8+ Rxe8 25.Qxd5 Nf8 26.g3 Ne6 27.Be5 Qb6 28.Qc4 Rd8 29.Rxd8+ Qxd8 30.Be4 b6 31.Kg2 g6 32.Qd5 Qxd5 33.Bxd5 Bg7 34.Bb8 a5 35.f4 Bd4 36.Kf3 h5 37.Ke4 Bf2 38.f5 gxf5+ 39.Kxf5 Ng7+ 40.Kf6 Bd4+ 41.Ke7 Nf5+ 42.Ke8 Bf2 43.Bxf7+ Kg7 44.Bxh5 Bxg3 45.Bxg3 Nxg3 46.Kd7 Ne4 47.Kc6 a4 48.bxa4 Nc3 49.Bd1, 1-0, M. Pavlovic (2483) – G. Kosanovic (2375) [C10], Vrnjacka Banja 2010.) 12.a3 0-0 13.c4 Qc7 14.Rfe1 Rfe8 15.Re3 c5 16.d5 exd5 17.Nf5 Bd6 18.cxd5 Bxh2+ 19.Kh1 Rxe3 20.Qxe3 Be5 21.Qg5 g6 22.d6 Bxd6 23.Bxf6 Nxf6 24.Qxf6 Be5 25.Qe7 gxf5 26.Qg5+ Bg7 27.Re1 Qd8 28.Qxf5 Qh4+ 29.Kg1 Rd8 30.g3 Qh6 31.Re7 Qg6 32.Qxg6 hxg6 33.Bc4 b5 34.Bxb5 Rd1+ 35.Kg2 Rd6 36.Bc4 Rf6 37.Rxa7 Bh6 38.a4 Kf8 39.a5 Bd2 40.a6, 1-0, J. Peters (2475) – A. Saidy (2385) [C10], US Game/60 Ch. Buena Park 1995.

8.Ned2 Be7 9.b3 0-0 10.Bb2 Nd5 (10…b5 11.a3 Rb8 12.Re1 a5 with reasonable play for Black in D. Brandenburg (2480) – A. Rustemov (2532), Bundesliga 2009; 10…b6 11.c4 Bb7 12.Qe2 c5 13.Rad1 cxd4 14.Nxd4 Bc5 15.Bb1 Qe7 16.N2f3 Rfd8 17.h3 Rac8 18.Nb5 a6 19.Nc3 Ba3 20.Ba1 h6 21.Nd4 Bd6 was fine for Black in P. Negi (2636) – D. Debashis (2400), Mumbai 2010) 11.g3 b6 12.c4 N5f6 13.Qe2 Bb7 14.Rad1 c5 15.Rfe1 Re8 16.Ne4 Nxe4 17.Bxe4 Bxe4 18.Qxe4 Nf6 19.Qf4 Qd6 20.Ne5 Rad8 21.Qf3 cxd4 22.Nc6 Rc8 23.Nxa7 Ra8 24.Nc6 Rxa2 25.Bxd4 Qc7 26.Nxe7+ Qxe7 27.Bxb6 Qb4 28.Bd4 Ra3 29.Bxf6 gxf6 30.Qxf6 Qxb3 31.Rd7 Rf8 32.Qg5+ Kh8 33.Qf6+ Kg8 34.Re5, 1-0, R. Felgaer (2584) – G. Spata (2286), Buenos Aires 2010.

8.Neg5 Be7 (Best is probably 8…Bd6 9.Re1 h6 10.Nh3 Bxf3 11.Qxf3 c6 with the usual sound but slightly passive position; 8…Bxf3 [8...h6? 9.Nxe6! fxe6 10.Bg6+ is the kind of attack White was dreaming of] 9.Qxf3 c6 10.Re1 Be7 11.c3 Nf8 12.Qh3 Qc7 13.g3 Bd6 14.c4 Qd7 15.Be3 h6 16.Rad1 N8h7 17.Nxh7 Nxh7 18.d5 cxd5 19.cxd5 e5 20.Bf5 Qe7 21.f4 e4 22.Bxe4 Nf6 23.Bb1 0-0 24.g4 Rfe8 25.g5 Bc5 26.Kh1 Bxe3 27.gxf6 Qc5 28.Qg3 g5 29.Qh3 Bd4 30.Qxh6, 1-0, F. Hellers (2565) – Ulf Andersson (2625), Eksjo 1993) 9.Nxf7 Kxf7 10.Ng5+ Kg8 11.Nxe6 Qc8 12.Re1 (12.Qe2 Bd6 13.Bc4 Nb6 14.Bb3 Ba4 15.c4 Bxb3 16.axb3 Qd7 17.c5 Re8 18.Re1 Nbd5 19.Rxa7? [19.cxd6 cxd6 20.f4 g6 21.f5 gxf5 22.Bg5 Kf7 23.Bxf6 Kxf6 24.Qf3 Rxe6 25.Qxd5 Rxe1+ 26.Rxe1 Rf8] 19...Bf4 20.c6 bxc6 21.Qd1 Rxe6 22.Bxf4 Nxf4 23.Ra8+ Ne8 24.g3 Nd5 25.Kg2, 0-1, I. Nataf (2370) – K. Arkell (2505) [C10], Hastings 1995) 12…Bd6 13.Bc4 b5 14.Bb3 Bd5 15.Bxd5 Nxd5 16.Nxg7 N7f6 17.Ne6 Qd7 18.f4 h6 19.a4 Re8 20.f5 a6 21.axb5 axb5 22.c3 Kf7 23.Qf3 Ne7 24.Rf1 Qc6 25.Qh3 Reg8 26.Bf4 Rg4 27.Be5 Rhg8 28.g3 h5 29.Rae1 Ned5 30.Rf3 h4 31.Kf2 Qb6 32.Kf1 Qa6 33.Qg2 b4+ 34.Qe2 Qxe2+ 35.Rxe2 hxg3 36.hxg3 bxc3 37.bxc3 Ne4 38.c4 Ndf6 39.Nxc7 Bxe5 40.dxe5 Rxg3 41.e6+ Ke7 42.Rxe4 Rxf3+ 43.Ke2 Rxf5, 0-1, A. Minhazuddin (2289) – N. Murshed (2413) [C10], Dhaka 2010.

8…Be7

Schell said: “8...Bxe4 9.Bxe4 Nxe4 10.Qxe4 c6 would have been more consistent with my drawing hope. It would have resulted in a position where White is slightly better as in the actual game but Black would have one less piece to worry about placing.”

Your suggestion of 8…Bxe4 seems best to me! In fact, the position after 8…Bxe4 9.Bxe4 Nxe4 10.Qxe4 c6 is pretty much viewed as a drawing line.

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 dxe4 4.Nxe4 Bd7 5.Nf3 Bc6 6.Bd3 Nd7 7.0-0 Ngf6 8.Qe2 Bxe4 9.Bxe4 Nxe4 10.Qxe4 c6 11.c4 Be7 12.b3 0-0 13.Bb2 a5 (13…Qa5 14.a4 (14.Qe3 Ba3 15.Bc3 Bb4 16.Bb2 Ba3 17.Bc3 Bb4 18.Bb2, 1/2-1/2 was the thrilling end of J. Polgar (2550) – A. Karpov [C10], Madrid 1992) 14…Rfd8 15.Rfd1 Bf6 16.Qc2 Nf8 17.Bc3 Qh5 18.b4 Ng6 19.Qe4 Nh4 20.Nxh4 Qxh4 21.f4 Rd7 22.g3 Qh5 23.Rd2 Rad8 24.a5 Qg6 25.Qxg6 hxg6 26.Kg2 g5 27.Kf3 gxf4 28.gxf4 g6 29.Ke4 Kg7 30.Rd3 Rh8 31.Ra2 a6 32.Rb2 Rh5 33.Be1 Kf8 34.Bg3 Ke7 35.Rbd2 Bg7 36.Be1 Rh8 37.Bg3 f5+ 38.Kf3 Bf6 39.Rd1 Rhd8 40.Bf2 Kf7 41.Ke2 Rh8 42.Bg3 Rhd8 43.Bf2 Rh8 44.Bg3 Rb8 45.Bf2 Rh8, 1/2-1/2, V. Vorotnikov (2465) – P. Lyrberg (2405) [C10], Heart of Finland op 1994) 14.Bc3 a4 15.Nd2 Nf6 16.Qf3 Qb6 17.b4 Qa6 18.a3 b5 19.Rac1 Rfd8 20.Rc2 Ne8 21.Ne4 Nd6 22.Nc5 Qc8 23.d5 Nxc4 24.dxe6 fxe6 25.Qg3 Bf8 26.Re1 e5 27.Bxe5 Qf5 28.Rce2 Qg6 29.Qc3 Rd5 30.Bd4 Bxc5 31.Bxc5 Rd3 32.Qc1 Rad8 33.Be7 R8d7 34.Qf4 h6 35.h4 Rd1 36.Qf8+ Kh7 37.Kh2 Rxe1 38.Rxe1 Nxa3 39.Re3 Rd3 40.Re5 Nc4 41.Rf5 Rd5 42.Rf6 gxf6 43.Bxf6 Qg8 44.Qe7+ Kg6 45.g4 h5 46.Bg5 Rxg5 47.Qxg5+ Kf7 48.Qf5+ Ke7 49.g5 Qe6 50.Qh7+ Kd6 51.g6 Qf5 52.Qh6 Qxf2+ 53.Kh3 Qf3+ 54.Kh2 Qf2+ 55.Kh3 Qf5+ 56.Kh2 Qf6 57.Qxh5 Ne5 58.Qd1+ Kc7 59.h5 Qh4+ 60.Kg2 Qg4+ 61.Qxg4 Nxg4 62.Kg3 Nh6 63.Kf4 a3 64.Kg5 Ng8 65.h6 Nxh6, 0-1, G. Buchicchio (2315) – M. Stojanovic (2504) [C10], Verona 2005

9.Ng3 Bxf3

Heading into that slightly inferior, somewhat passive, but fully playable position. The real alternative is 9…0-0 but then 10.Ne5! appears to favor White:

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nd2 dxe4 4.Nxe4 Bd7 5.Nf3 Bc6 6.Bd3 Nd7 7.0-0 Ngf6 8.Ng3 Be7 9.Qe2 0-0 10.Ne5 Nxe5 11.dxe5 Qd5 (11…Nd7 12.Rd1 Qc8 13.Nh5 gives White good attacking chances) 12.f4 Nd7 13.c3 Nc5 14.Bc4 Qd7 15.f5 Kh8 16.f6 gxf6 17.exf6 Bd6 18.Bh6 Rg8 19.Bg7+ Rxg7 20.fxg7+ Kg8 21.Nh5 Be7 22.Rad1 Qe8 23.a3 b5 24.Ba2 a5 25.Rf4 Rd8 26.Rdf1 Bg5 27.Rxf7, 1-0, M. Kobalia (2602) – A. Rustemov (2598) [C10], Russia 2002.

10.Qxf3 c6 11.b3 O-O 12.Bb2 Re8

Schell said: “Overprotecting the dark square bishop and freeing the f8-square for either a knight, in defense of h7, or bishop, in defense of g7.”

All that sounds very impressive (and all that stuff is useful), but what is your plan? What gains do you hope to make? How are you going to create weaknesses in the enemy camp? What’s your agenda, and how do you intend to pursue it? The problem is that White has many ways to improve his position (gain more space, try to create a position where the two Bishops rule, etc), but what does Black have? Since you have the black pieces, it’s your job to ask these questions and then solve them. Otherwise you’re not doing anything but waiting around to die.

Looking at the position after 12…Re8 in my database, White won the overwhelming majority of games. Yes, your move defends various things, but it’s a somewhat passive move in a passive position. Of course it’s not fatal or even bad! But if you continue to play in the same vein, it will be.

Now take a look at the following game (Black played 12…Qc7 instead of 12…Re8), and you can see how Black is doing everything possible to generate his own play:

A. Simutowe (2457) – V. Burmakin (2611) [C10], Cappelle La Grande 2008

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 dxe4 4.Nxe4 Bd7 5.Nf3 Bc6 6.Bd3 Nd7 7.Qe2 Ngf6 8.Ng3 Be7 9.0-0 Bxf3 10.Qxf3 c6 11.b3 0-0 12.Bb2 Qc7 13.c4 Rfd8 14.Rad1 Nf8 15.Ne2 Qa5 16.a3 Qh5 17.Qg3 Bd6 18.f4 Ng6 19.h3 b5 20.Qe1 bxc4 21.bxc4 Rab8 22.Bc1 Ne7 23.Rf3 Bc7 24.Bd2 Nf5 25.Qf2 Qh4 26.Qf1 Ne8 27.Bc3 Qe7 28.Bb4 Bd6 29.c5 Bc7 30.Qf2 Qh4 31.Qf1 Qe7 32.Qf2 Qh4 33.Qf1 Qf6 34.Bc3 Qe7 35.Bc2 Nf6 36.Qf2 Nd5 37.Ba1 Qh4 38.Ba4 Qxf2+ 39.Kxf2 Nfe7 40.g3 Ba5 41.Rb3 Rxb3 42.Bxb3 h5 43.Bc2 Nc7 44.Rb1 Ncd5 45.Rb7 Ra8 46.Bb2 Kf8 47.g4 hxg4 48.hxg4 Ke8 49.Be4 Bc7 50.Bc1 Kd7 51.Bd2 g6 52.g5 Kc8 53.Rb1 Kd7 54.Rb7 Rh8 55.Rxa7 Rh2+ 56.Bg2 Kc8 57.Ra8+ Bb8 58.Kg3 Rh8 59.Ra4 Rh5 60.Kf2 Rh4 61.Bxd5 Nxd5 62.Kg3 Rh5 63.Kg2 Kb7 64.Rc4 Rh4 65.Kg3 Rh5 66.Kg2 Rh4 67.Kg3 Rh5 68.Kg2 Rh4 69.Rc1, 1/2-1/2.

There’s nothing wrong with your 4…Bd7 line in the French. But if you want to play it, you need to look over tons of games like the one above so you can get a feel for the right setups, plans, and dynamics. It’s not a matter of memorization. It’s a matter of understanding the positions and being able to make use of that understanding no matter what White might try.

This is how ALL openings need to be studied. It’s easy, it’s fun, and it leads to great results. Finally, I need to add one last critical point: losing this game can be considered a blessing. It’s how you’ll master your opening. By using every loss as a lesson, you are able to gain experience and eventually master the systems you play.

13.Rfe1 Qc7

Schell said: “I had no clue what to do here.”

Allow me to go a little further in the “how to study openings” department. The following game features this position, with the exception that white’s a whole move up (he didn’t play Qe2 and thus didn’t move his Queen twice). Though it’s not the exact same position, there’s still lots of gold to be mined, and you should study anything that’s even in the same zip code as your system:

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 dxe4 4.Nxe4 Bd7 5.Nf3 Bc6 6.Bd3 Nd7 7.0-0 Ngf6 8.Ng3 Bxf3 9.Qxf3 c6 10.b3 Be7 11.Bb2 0-0 12.c4 Re8 13.Rfe1 Qc7 14.Rad1 Rad8 15.a3 Nf8 16.h4 Rd7 17.h5 h6 18.Bb1 Red8 19.Ne4 Nxe4 20.Rxe4 Nh7 21.Rg4 f5 22.Rg6 Bf6 23.Re1 Bxd4 24.Bxd4 Rxd4 25.Rgxe6 Ng5 26.Qxf5 Nxe6 27.Qh7+ Kf8 28.Bg6 Qf4 29.Qh8+ Ke7 30.Qxg7+ Kd6 31.Qxb7 Rd2 32.c5+ Kxc5 33.Qxa7+ Kd6 34.Bf7 Nc7 35.b4 Qd4, 0-1, I. Salgado (2366) – A. Hoffman,Alejandro (2461) [C10], Malaga 2006.

The lesson from this game was basic but very important: Black can tie his opponent down if he manages to build serious pressure against white’s d4-pawn.

Now I’ll go completely crazy in my quest to explain opening study. We’re going to start with 1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.Nf3 Nf6 4.e3 Bf5 5.Nc3. I hear everyone screaming, “Silman’s an idiot, he’s forgotten that we’re studying the French, not the Slav!”

Fair enough, but let’s play a few more moves: 5…e6 6.Bd3 Bxd3 7.Qxd3 Nbd7 8.0-0 Be7 9.e4 dxe4 10.Nxe4 Nxe4 11.Qxe4 and we pretty much have the same position that we explored in the note to black’s 8th move (the recommendation of 8…Bxe4), except this time black’s a move ahead!

Though it’s almost the same position (of course, the extra tempo helps Black), the ideas ARE interchangeable, and studying the Slav position, even though you are playing the …Bd7-c6 line in the French, is a good idea!

Here’s an example of black’s play in that almost identical Slav position:

1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.Nf3 Nf6 4.e3 Bf5 5.Nc3 e6 6.Bd3 Bxd3 7.Qxd3 Nbd7 8.0-0 Be7 9.e4 dxe4 10.Nxe4 Nxe4 11.Qxe4 0-0 12.b3 a5 13.Bb2 a4 14.Qc2 b5 15.Rad1 axb3 16.axb3 bxc4 17.bxc4 Qa5 18.Ra1 Qc7 19.Ne5 Nxe5 20.dxe5 Bc5 21.Rxa8, 1/2-1/2, M. Gagunashvili (2574) – I. Rausis (2512) [D12], Dhaka 2009

For the vast majority of players who don’t want to put that kind of intensity into opening study, don’t panic! The main message is simple, painless, and important: learn the basic plans, ideas, pawn structures, and tactics of your openings (it’s far easier than you might think!) and you’ll discover that your opening play (and the middlegame play that follows) reaches a whole new level with minimum work and minimum memorization.

14.Rad1 a5

Schell said: “Trying to weaken White’s structure with 15...a4 and then exchange some pieces.”

Starting in the position after 14.Rad1, let’s look at one suggestion, and one game. In both instances, you’ll see Black fighting hard to change the nature of the position so that it gives him something to crow about:

In the end, it doesn’t matter if either 14…Qa5 15.a3 Bxa3 or 14…b5 equalize. What does matter is the attitude behind each one! In both cases, black’s building something and striving to make a positive change in the position.

15.a3 Qb6?

Schell said: “My reasoning for this move was bad – I had hoped to prevent 16.c4, which is possible anyway. 16.c4 Qxb3 17.Bxh7+ and the queen is removed from play. My opponent had something more ambitious in mind.”

The problem with your reasoning isn’t that you missed the tactical refutation of 16.c4 Qxb3 (17.Bxh7+), but in your desire to defend. You’re still not building anything. Instead, you’re merely reacting to your opponent’s ideas.

16.Nf1 Rad8 17.Ne3 c5?

This is a serious mistake. You were already worse, but now you rip open the position for white’s Bishops. Never forget the minor piece battle. If you have Knights and he has Bishops, you usually don’t want to open things up!

18.dxc5?

18.d5! exd5 19.Nxd5 Nxd5 20.Qxd5 Nf6 21.Qc4 (21.Qf5!?) 21…Qc6 22.a4 is very nice for White since his Bishop pair rule the board and assure White a serious plus in the middlegame and the endgame.

18…Bxc5

Schell said: “18...Nxc5 is more accurate. I was afraid of 19.Nc4 Qc7 20.Be5 picking up tempos, but black is hanging around.”

Once again your move was based on a reaction to what your opponent might do to you. If you liked the look of 18…Nxc5, but weren’t enthused about 19.Nc4 Qc7 20.Be5, you should have looked for a different Queen retreat. In other words, don’t give up on a line at the first sign of trouble. Thus, after 19.Nc4 you could play 19…Qa7! and though you’re worse, you’re still very much in the game.

19.Nc4

19.Qg3!?

19…Qc7 20.Ne5 Nf8

Schell said: “20...Bxa3 ideas fail to an eventual pin on the h2-b8 diagonal from White's queen.”

Mr. Schell is referring to 20…Bxa3 21.Bxa3 Nxe5 22.Qg3 Nfg4 23.h3.

However, instead of the passive 20…Nf8, I would have preferred 20…Nxe5 21.Bxe5 Qe7 22.Bxf6 Qxf6 23.Bxh7+ Kxh7 24.Qh5+ Kg8 25.Qxc5 Rc8 26.Qxa5 Rxc2 and though white’s a pawn up, the active c2-Rook will make it very difficult for White to cash in on his small material plus.

21.h4

21.Bb5!?

21…Qe7?

Schell said: “Black is quite tied up; lashing out as I did in the game was grossly ineffective.”

You probably had to try 21…Ng6 22.h5 Nh4 (22…Nxe5 23.Bxe5 Qe7 24.h6 is winning for White) 23.Qf4 Nf5 24.Bxf5 exf5 25.Rxd8 Qxd8 26.Qxf5 (26.h6? Ng4) 26…Qd5 when we get an interesting position: black’s a pawn down, but white’s powerful light-squared Bishop is gone, white’s Knight is pinned along the e-file, and black’s pieces are suddenly active. Since 27.h6 Qd2 28.Rf1 Qxh6 29.Nxf7 Bxf2+ 30.Qxf2 Kxf7 isn’t as bad for Black as a first glance might make you believe, White should try something less forcing on his 27th move: 27.a4 h6 and one problem White has is that the h5-pawn will be loose if the Queen ever takes its eyes off of it.

22.Nc4 Nd5?

This looks aggressive, but it doesn’t have any real point. In fact, its absence from f6 weakens black’s kingside defense. Instead, 22…Rd5!? is possible, while 22…Ng6 23.h5 Nh4 24.Qh3 Nf5 25.Bxf5 exf5 26.Rxe7 Rxd1+ 27.Kh2 Bxe7 might be worth a try since 28.Qxf5? is met by 28…Rd5. However, 28.Bxf6 Bxf6 29.Qxf5 is clearly better for White, but perhaps this is the best line of a bad lot.

23.Qg3

Even stronger is 23.h5 h6 24.Be4 when it’s hard to find a good move for Black since most lines have Black dropping pawns on a5 or b7.

23…g6

Opening up the a1-h8 diagonal looks pretty scary!

24.Be4

Black’s now lost. The rest of the game didn’t last long: 24…b5 25.Nxa5 Bd6 26.Qf3 Qxh4 27.g3 Qe7 28.Bxd5 Bxa3 29.Nc6 Qc5 30.Bxa3 Qxa3 31.Nxd8, 1-0.

Schell said: “The soft clink of knight takes rook followed by the removal of the piece from the board was enough for me to finally bow my king to his. I think this game is an excellent example of how to convert a ‘slightly better’ position into a win through almost no effort at all!”

The reason White didn’t seem to make much of an effort is because Black never challenged his opponent with a plan of his own. Better to die while attempting to build something than to sit around and do nothing, knowing that death is rushing to meet you.

~ Lessons From This Game ~

* If you don’t try and push a plan/agenda of your own, you will find that you lose most of your games without a fight.

* What is your plan? What gains do you hope to make? How are you going to create weaknesses in the enemy camp? What’s your agenda, and how do you intend to pursue it? In every game you play, it’s your job to ask these questions and then solve them.

* If you want to be really good at an opening, you need to look over tons of games so you can get a feel for the right setups, plans, and dynamics. It’s not a matter of memorization. It’s a matter of understanding the positions and being able to make use of that understanding no matter what the opponent might try.

* For the vast majority of players who don’t want to put too much time into opening study, don’t panic! The main message is simple, painless, and important: slowly but surely learn the basic plans, ideas, pawn structures, and tactics of your openings (it’s far easier than you might think!) and you’ll discover that your opening play (and the middlegame play that follows) reaches a whole new level with minimum work and minimum memorization.

* Never forget the minor piece battle. If you have Knights and he has Bishops, you usually don’t want to open things up!