USA—USSR

In 1945, right after WWII ended, a team of United States players competed against a team of Soviet players in a chess match via radio. While the U.S. team expected stiff competition, there was little doubt in the minds of most Americans that they would win. The unpleasant surprise was that not only did they not win, but they were massacred. Only then was the concealed power of Soviet Chess fully realized in the West.

A decade later, a U.S. team went to Moscow and received an even worse drubbing.

Inbetween these two events were two another USA-USSR events

sandwiching a USA-USSR non-event.

1946:

First came an invitation by the Soviets for an American team to play a live rematch in Moscow in 1946. The US accepted the invitation and the match was set for Sept. 9-12. The Americans planned to sent Maurice Wertheim, as team captain and Kenneth Harkness as team manager; Weaver Adams, Arthur Dake, Arnold Denker, Reuben Fine, Al Horowitz, Isaac Kashdan, Alexander Kevitz, Albert Pinkus, Sammy Reshevsky, Herman Steiner and Olaf Ulvestad completed the roster. Also on board were Miss Anna Goldsborough, PR director from the American Society for Russian Relief, Hilda Tunic, secretary, as well as some spouses: Mrs. Harkeness, Mrs. Denker, Mrs. Ulvestad, Mrs. Horowitz and Mrs. Dake.

The Soviet line-up consisted of Mikhail Botvonnik, Paul Keres, Vasily Smyslov, Isaac Boleslavsky, Alexander Kotov, Salo Flohr, Viacheslav Ragozin, Andor Lilienthal and David Bronstein with Grigory Levenfish as team manager . Later, Ulvestad wrote,"The Americans and Soviets had exchanged line-ups; i.e. each man on each team knew who his adversary was to be." So much time was spent studying and preparing for the opponents' styles and weaknesses. The plan was for two rounds to be played in Moscow and four rounds played in New York the following year.

Behind Samuel Reshevsky (in front), l-r, are Alexander Kevitz, Isaac Kashdan,

Weaver Adams and Mrs. Dake, with Arthur Dake ann Albert Pinkus in the back.

Travel, a more difficult thing in those days, was compounded further following the war and, as it turned out, all members of the American team didn't all arrive in time. Steiner and Denker, as well as five members of the Soviet team were stuck in Groningen, Holland where they were participating in the tournament (won by Botvinnik), due to weather. The plane carrying the rest of the team took off from La Guardia en route to Stockholm, first landing in Copenhagen. From Stockholm the Russian steamer, Beloostrov, went to Leningrad with a stop-over in Helsinki. After a day of sight-seeing in Leningrad, the parties flew to Moscow and checked into the Hotel Metropole. The match didn't start until Sept.12, the day it was supposed to have ended.

The formal opening of the match was at 5:45 pm in the Hall of Columns at the House of Trade Unions with 1500 spectators seated and a 1000 more standing in the foyer watching the demonstration boards. The event began with speeches by the Chairman of Sports, Nikolai Romanov, by Sergei Pushnov, the vice-chairman, by Elbridge Durbrow, Charge d'Affaires from the U.S. Embassy and by Maurice Wertheim. Max Euwe served as referee.

Fine (l) plays Kere (r) as Euwe observes

Smyslov - Denker

Lilienthal - Dake

Ulvestad - Bronstein

Mikhail Botvinnik

The US team lost the first round by 4 pts. (7-3), but made a come-back attempt in the second round, losing only by 1 pt. (5½ -4½), with several winning games lost due to time pressure. This helped ease the embarrassment from the 1945 Radio Match somewhat.

The 1947 Non-Event:

The 1946 match was originally envisioned as a two-part event with half the games played in Moscow and half played in New York City.

Nikolai Mikhailovich Zubarev On the beginning of March 1947 the US sponsors sent the Soviets their invitation to play the rest of the match during the last two weeks of August, allowing the Soviets to send a group of up to 20, including team members, managers, wives and officials. On March 25, after receiving no reply for nearly a month, the US called Nikolai Zubarev of the USSR Committee on Physical Culture and Sports, explaining that a confirmation was needed as quickly as possible in order to secure the playing hall (the Auditorium of the Henry Hudson Hotel which required a commitment by April 10). Zubarev was unable to make a commitment at that time, and on April 10, cabled the US to say he could not provide an answer before at least May. The US was forced to cancel the match with the hope, never realized, to reschedule things for the next year.

On the beginning of March 1947 the US sponsors sent the Soviets their invitation to play the rest of the match during the last two weeks of August, allowing the Soviets to send a group of up to 20, including team members, managers, wives and officials. On March 25, after receiving no reply for nearly a month, the US called Nikolai Zubarev of the USSR Committee on Physical Culture and Sports, explaining that a confirmation was needed as quickly as possible in order to secure the playing hall (the Auditorium of the Henry Hudson Hotel which required a commitment by April 10). Zubarev was unable to make a commitment at that time, and on April 10, cabled the US to say he could not provide an answer before at least May. The US was forced to cancel the match with the hope, never realized, to reschedule things for the next year.

1954:

The events of 1954 had it's shaky beginnings in 1953.

In May of 1953 the chess media announced that the Soviets would be sending a team to New York for match with an American team to take place on July 15 to 23 - accepting the standing invitation from 1946.

The 1946 invitation had been renewed by Al Bisno, team captain and manager, during the Olympiad held in Helsinki in August 1952:

In the face of continuing international tension on the political front, talk persists of a possible chess-team match between the Soviet Union and the United States. Alexander Bisno, who represented the United States Chess Federation at the recent international chess assembly at Stockholm, reports that the proposal for such a match overshadowed most other business on the agenda. The Soviet group was persuaded by Bisno to consider proposals Final approval of the match will depend upon assent of the Soviet Chess Federation and the U.S.C.F

—Louisville "Courier-Journal," Nov. 16, 1952

The team members had been selected, the Hotel Roosevelt reserved, wall boards purchased, rooms for the visitors secured and paid for, visas approved through a special action by the U.S. Attorney General when suddenly everything just went to pieces. The Russians made sudden stipulations. They wanted their team to stay at the Russian-owned Glen Cove Estate in Long Island (the former Killenworth Estate of George DuPont Pratt) but the visas, meticulously attained and very specific, were only for New York. The team was told they could visit Glen Cove but not stay there. The team, which at that time was in Paris, returned to Russia and the match was canceled. The U.S. was rightfully upset with the soviets refusal to compromise. At the time the arrangements for the match were being finalized, the U.S. asked the Soviets if they would prefer a hotel in the city or their Glen Cove estate. The Soviets failed to respond at all to that point and the U.S. made the hotel reservations. The U.S. felt the Soviets used the accommodations as an excuse to back out. (it should be noted that Joseph Stalin died in July or 1953, though he was out of power by then due to poor health and that the Korean War had reached an armistice that same month.).

"Sydney Herald," July 11, 1953

Killenworth Estate, the Soviet diplomatic retreat - 49 rooms, 36 acres.

In August the Soviets contacted the U.S. with an invitation to come to Russia in November or whenever convenient "in the interest of strengthening friendship." The invitation was sent from the chairman of the All-Union Chess Society to Samuel Reshevsky. Reshevsky forwarded it to Harold M. Phillips, the USCF president. He rejected the invitation but re-invited the Soviets to come to New York in 1954: "We want to repay the hospitality we received from the Russians in 1946, and, at this point, the idea of going to Russia does interest us too much."

The disappointed American team

Early in 1954 the Soviets once again accepted the invitation to come to New York, but it fell on skeptical ears:

But by May things looked pretty well established:

The Grand Ballroom of Hotel Roosevelt in New York City

Smyslov had just finished an exhausting World Championship match against Botvinnik which had extended from March 16 to May 13 and which ended in a 12-12 tie leaving Botvinnik the title but too tired to attend this international match. The U.S. Championship ( May 29- June 13) was wrapping up when the Soviets arrived in New York on June 11. The Soviet team visited the Marshall Chess Club where it was taking place. Arthur Bisguier won it undefeated with a score 10-5. Larry Evans who was the defending champion came in second with a score of 9-4.

The Grand Ballroom held about 1000 seats, but the match was standing-room-only. In adjoining rooms, the overflow crowd was treated to analysis and discussion by George Koltanowsky, Eliot Hearst and Nate Halper.

U.S. Team Captain: Alexander Bisno

USSR Team Captain: Igor Bondarevsky

USSR Chess Chief: Dmitri Postnikov

Referee: Hans Kmoch

The American team comprised of Samuel Reshevsky, Albert Denker, Max Pavey Donald and Robert Byrne, Israel Horowitz, Arthus Bisguier and Larry Evans with Alexander Kevitz and Arthur Dake as alternates.

The Soviet Team comprised of Vassily Smyslov, David Bronstein, Paul Keres, Yuri Averbach, Efin Geller, Alexander Kotov, Tigran Petrosian, Mark Taimanov.

The results (from the American side) were:

Bd. 1 Reshevsky - Smyslov =4

Bd. 2 Denker - Bronstein -3

Dake - Bronstein -1

(Dake replace Denker who came down with a viral infection)

Bd. 3 Pavey - Keres +1-2

Kevitz - Keres -1

(Krevitz was substitued for Pavey by the decision of the team captain)

Bd. 4 D. Byrne - Averbach +3-1

Bd. 5 Horowitz - Geller =2-2

(Horowitz had a side-bet of $100 against $250 that he would have a plus score.

He lost the bet)

Bd. 6 R. Byrne - Kotov +3-1

Bd. 7 Bisguier - Petrosian =2-2

Bd. 8 Evans - Taimanov +2=1-1

It was a splendid afair for chess. The visiting team was treat like royalty and became darlings for the news media:

For one glorious week chess was front-page news in the United States! Newsreel, TV, newspaper, news-magazine cameramen and reporters covered the arrival of the Soviet team, the opening and closing rounds of the match. Editors of the metropolitan press recognized the news value of the presence of a Soviet chess team, opened their columns to wide coverage of the contest. Feature stories and round-round results, with game scores and big pictures appeared in the New York Times, the New York Herald-Tribune and other papers.

Another view of the playing hall

Eliot Hearst reported in depth for Chess Life.

So says Al Horowitz

During a reception after the match, Eliot Hearst made the following colorful observations:

Petrosian: ...the baby of the Russian team, at 24, and who, though a native of Armenia, is described as Russia's Capablanca.

Geller: . . .served as an aviator in the war and is now a Professor of Agriculture at the University of Odessa besides boasting the muscles of a strong amateur athlete.

Keres: . . .whom several women of the Marshall have commented on as resembling a movie star, does not look his 38 years, and in fact cold pass for under 30; he speaks English well. . .

Averbakh: . . .a tall, blond and quiet fellow stands nearby and comments modestly to a query that the only reason he won the recent USSR championship was because 'all the good players did not play.'

Syslov: a redhead, is somewhat heavier than we expected and his dignified but friendly air is apparent even amidst the confusion of the crowd.

Bronstein: ... is a short, slight fellow whose baldness is restricted to the center of his head - rather than to its peripheries where his black hair is by no means absent; despite the fact that we have heard he speaks good English, he exhibits no inclination to converse in that language with anyone.

Boleslavsky: ... looks more typically 'Russian' to us than any of the other team members; his heavy built may or may not be the characteristic that gives us that impression. We regret to hear that he is slowly going blind and has only a few years of possible tournament competition remaining.

Bronstein played skittles with Bisguier, drawing the first 4 and then winning 6 straight before drawing 3 more.

Afterwards the US team played a mixture of Argentine players and two Russians, Bronstein and Boleslavsky, winning all four rounds.

It was noted several times that the Soviet team comprised of 8 professionals, while the US team, with the exception of Reshevshy, was made up of all amateurs. The secular press also pressed this distinction.

The most exciting game of the match. Geller thought about 40 minutes considering the possibilities of 21. Q-R6, a Queen-sacrifice which comes close to winning - but probably loses. Finally the Russian decided just to win a pawn and the resulting position gave Horowitz good chances. In time-pressure Geller played for a win and allowed Horowitz to sacrifice the exchange which led to a win but Horowitz missed it in time pressure. The American missed several winning lines, including a gain of a Rook. At resumption after adjournment Horowitz still had a slight advantage but agreed to a draw without continuing.

"The best game of the round, Robert played well against the King's Indian Defense set up by Kotov and had a distinct advantage going into the middle game. Kotov tried P-QR6 at a crucial stage, a move which involved the sacrifice of a piece which Byrne should not had accepted. After a Knight sacrifice had been taken, Kotov continued neatly and regained the piece with a Pawn to boot in a combination based on a queening possibility. Bishops of opposite color left Byrne with some drawing opportunities but the Russian Grandmaster's careful handling of the ending eventually scored him the point after an adjournment had been taken."

In a postscript called "Odds and Ends," Eliot Hearst wrote:

The Russians spent a good part of the days preceding the initiation of the first round of play listening to the Army-McCarthy hearings on TV in their suite of rooms at the Hotel Roosevelt. Outside of saying they 'enjoyed it,' no further comment was forthcoming

. . . . George Koltanowsky treated the Russian aggregation to a visit to Radio City Music Hall where 'Executive Suite' and the usual top-notch stage show were on the program. The Soviet masters applauded and cheered profusely as the Rockette chorus line performed, and otherwise took great pleasure in the rest of the stage show, even though the movie, based as it was on a battle for control of an industry, is said to have moved them little

. . . .David Bronstein was the 'hero' of a couple of the best stories to be related about the international gathering. Bronstein went to see 'How to Marry a Millionaire' on the first two off-days of the tourney and, after seeing it twice, came over to a group of us Americans and asked us if we knew of any other pictures starring Marilyn Monroe that were playing in New York ! ! Now we know what he liked best about America!

. . . Bronstein's desire for lemon juice served to confuse many of the stewards at the hotel. Once he ordered a glass during his game and was queried whether he meant 'lemonade' - with lemons, sugar and water. 'No!' said the Russian, 'I want pure lemon juice.' It took nine lemons to fill his glass and, after drinking it down, Bronstein swiftly developed a winning position! . . . A visitor to the tournament rooms insisted on seeing the U. S. team captain, claiming that he could supply the U. S. with a player who would surely smash his Soviet opponent to its. Further questioning revealed that this player, who shall remain nameless, was formerly a N. Y. club member of average strength who is now confined to an insane asylum! After thanking the visitor for his patriotism, U.S. team officials expressed regrets that the team could no longer be changed and that the unknown grandmaster would be ineligible to play. (But maybe we could have used a few crazy moves against the Russians!?)

. . . Don Byrne relates that he was very nervous before the start of the match games and to alleviate his nervousness he sat at home all day reading Nathaniel Hawthorne's best works rather than studying recent games. After the fine score he built up against Averbakh we might recommend Hawthorne as apt preparation for future members of the U. S. team, too!

. . . When Al Bisno asked his young son, Paul Morphy Bisno, whom he want to win, he got an answer he least expected: "My friend Kotov;" it seems the Russian grandmaster and the junior Bisno had become real pals during the course of the match!

. . . The banquet at the conclusion of the match revealed Taimanov and Smyslov as real masters in other fields. Taimanov, a concert pianist, played several selections from Chopin and got excellent 'notices' from even the most caustic of the musical cognscenti in the audience, while Smyslov's rich baritone voice (accompanied by Taimanov) got bravos from the audience also. It is said that Smslov would have been a professional opera singer if it didn't take so much time from his chessic endeavors!

. . . Mary Bain, dining with Postnikoff, Keres and Bronstein, won plaudits from this trio for her exhibition of the knight's tour blindfolded

. . . Forry Laucks of the Log Cabin C. C. arranged a banquet celebrating fellow member Don Byrne's final score against Averbakh; at the diner Byrne was boomed for a grandmaster rating!

. . . The Rusian players at all times revealed themselves to be gentlemen and we hope that this attitude toward their American opponents will continue in the reports of the match which they'll give on their return to Russia (although one doubts whether the Soviet players themselves will be the ones to discuss the match!)

Just before coming to New York, the Soviet Team was in South America to play a match with the Argentinian team. The Argentinian team score a half point less than the US team, but Smyslov didn't participate:

Chess Life reported in the July 20, 1954 issue that the same Soviet team (with the addition of Kira Zvorykina and Isaac Boleslavsky and with Elisaveta Bykova replacing Alexander Kotov) had just beaten the 10 board British team 18.5-1.5 (+16=3) in early July.

The British team comprised of Alexander, Golombek, Wade, Penrose, Broadbent, Milner-Barry, Barden, Fairhurst, Miss (Eileen) Tranmer and Miss (Patricia Anne) Sunnucks.

Caricature sketches made during the match:

F.B. Dolbin: self-portrait

1955:

The Soviets invited a U.S. team to play in Moscow in 1955. There was a lot of controversy putting together the sponsorship and the lineup. As an example:

"Chess Life," April 4, 1955

"Chess Life, " May 5, 1955 reproduced this data

Maybe it was due to the controversy, but "Chess Life" gave this event, held from June 29 to July 6, minimal coverage. However it was covered in the mainstream media including "Life" magazine as a hopeful example of Soviet-American relations.

"Chess Life," July 20, 1955

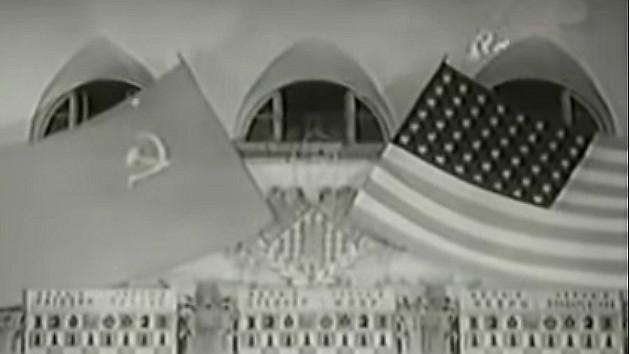

Chess playing hall bookended by Soviet and American flags

Dmitri Postnikov, the Soviet Sports Minister, threw a "Fourth of July" gala. as the tournament occurred during America's Independence Day. The party included this surprising cake (notice the chess king and queen):

First Secretary, Nikita Kruschev, Al Bisno (Alexander Kotov is behind Bisno)

Reshevsky playing Botvinnik in Round 1

This upset seems to have made Reshevsky a superstar in Russia.

Here he is signing autographs for his adoring Russian fans

"Sports Illustrated" of July 4, 1955 gave this slightly different viewpoint:

Chess is virtually the Russian national game. If nine Russians suddenly appeared in New York to take on the Yankees the situation would be roughly comparable to that of the Americans in Moscow. There is no element of chance in chess. The oldest game in the world that is still played in its original form, chess is strictly logical: the American team can hardly count on any outside circumstances providing breaks, blunders or flukes. But surprise, boldness, tenacity, the refusal to accept defeat are potent factors within a logical framework, and in that sense the appearance of the Americans in Moscow comes up to an exacting standard: it's good chess.

It is largely a matter of luck that some of the American team will be able to play. Back in 1950, when Arthur Bisguier, then 20, won the United States Open Chess Championship in Detroit, an automobile-load of homeward-bound players smashed up near Batavia, New York, and four players, including the first-place winner and two who tied for third in the tournament landed in Genesee Memorial Hospital. Since everybody in the car was a youthful chess prodigy, much of the present-day chess talent of the United States nearly vanished right there. Bisguier suffered broken ribs and a gashed forehead. Larry Evans, then 18, is now the second-ranking American player, and flying to Moscow. According to the book, the Americans have a heavy handicap against the Russians, but it would be much worse without these two. In the Russian-American match of 1954 (which the Russians won 20 to 12) Evans won two games, lost one and drew one—the highest score of any of the Americans, except Donald Byrne, who won three and lost one.

It is impossible to imagine a carload of Russian masters in a similar situation. Russia's chess masters are mature men, well-groomed, dignified, their appearance suggesting a group of prominent professors. In comparison the Americans suggest a group of revolutionaries—wild, unpredictable and unyielding in their resistance to Soviet chess authority. Donald Byrne is 25, a recent Yale graduate now studying for a doctorate at the University of Michigan. His older brother, Robert Byrne, is on his way to his third match with the Russians: he won his game from Russia's Grand Master, David Bronstein, in 1952's chess Olympics at Helsinki, which astonished the Russians so much they proclaimed him an international grand master. He lost one game and drew three in the Russian-American match last year.

Samuel Reshevsky, the strongest American player, who drew all four of his games with Smyslov last year, conforms more closely to the popular idea of a master—slight, bespectacled, balding, with an implacable will to win that made him a chess master before most of his teammates were born. Israel Horowitz, editor of The Chess Review, Herman Steiner and Isaac Kashdan are the sixth, seventh and eighth members of the American team—veteran chess players, as are the alternates, Max Pavey and Alexander Kevitz.