MIT Study Finds Chess Players Perform Worse When Air Quality Is Low

With the start of the 2023 Airthings Masters just around the corner, chess fans may already be expecting a renewed focus on how air quality affects players.

After all, the first event of the new $2 million Champions Chess Tour season is sponsored by the leading maker of air quality monitoring devices.

But the results of a new study published on Thursday co-authored by an MIT researcher appear to shed more light on an intriguing idea that impacts chess players at all levels: indoor air pollution really does affect play.

The research, gathered from a study of German's top league, the Schach-Bundesliga, shows that chess players perform objectively worse and make more suboptimal moves, as measured by a computerized analysis of their games, when there is more fine particulate matter in the air.

More specifically, given a modest increase in fine particulate matter, the probability that chess players will make an error increases by 2.1 percentage points, and the magnitude of those errors increases by 10.8 percent.

In this setting, at least, cleaner air leads to clearer heads and sharper thinking.

But the importance of air quality is a factor already being considered in the chess world—and by some of the world's best players.

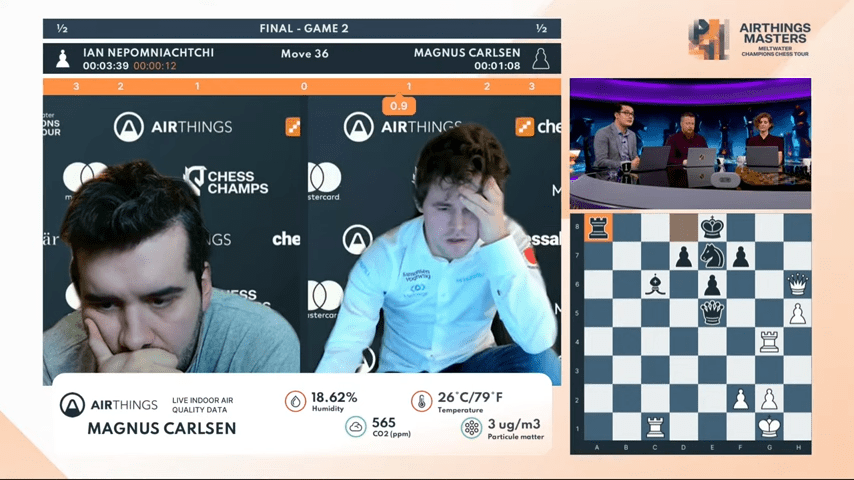

During the last Airthings Masters event in February last year, Champions Chess Tour viewers could see the air quality data on their screens in real-time relayed from players’ homes.

GM Magnus Carlsen ran out the winner—needless to say, he had near-perfect air quality. His fine particulate matter level (measured at 3ug/m3) was good, as was his concentration of carbon dioxide.

Later in the Champions Chess Tour season, the $210,000 Oslo Esports Cup was held at the Tour venue in Oslo. Along with computers, desks, chairs, and filming equipment, three Airthings View Plus devices were placed in key positions around the building, such as the playing area, studio, and lobby.

This allowed Airthings and the Tour to gain insights into seven different indoor air quality data points, including CO2, humidity, Particulate Matter (PM), and Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) at the event.

Poland's World Cup winner Jan-Krzysztof Duda eventually overtook fellow Airthings Ambassadors Carlsen and Liem Quang Le in the last round to clinch the $210,000 Oslo Esports Cup.

Tour Director Arne Horvei said at the time: "Keeping the air quality conditions stable in a studio full of lights, LED panels and smoke generators is of course a challenge. We can always feel the temperature but having the Airthings devices to help us monitor the CO2 and PM level in the Esports Arena really helps us be proactive in taking measures to make the playing conditions for the best chess players in the world optimal."

Comments from Juan Palacios, an economist in MIT’s Sustainable Urbanization Lab, and co-author of the newly published paper detailing the study’s findings, appear to back up what Airthings have said about air quality.

“We find that when individuals are exposed to higher levels of air pollution, they make more mistakes, and they make larger mistakes," he said.

The paper, "Indoor Air Quality and Strategic Decision-Making," appears online in the Management Science journal.

Air Quality Matters

In a press release issued on Wednesday, researchers explained how they studied the performance of 121 chess players in three seven-round tournaments in Germany in 2017, 2018, and 2019, comprising more than 30,000 chess moves. The scholars used three web-connected sensors inside the tournament venue to measure carbon dioxide, PM2.5 concentrations, and temperature, all of which can be affected by external conditions, even in an indoor setting.

Because each tournament lasted eight weeks, researchers said it was possible to examine how air-quality changes related to variations in player performance. In a replication exercise, the authors found the same impacts of air pollution on some of the strongest players in the history of chess using data from 20 years of games from the first division of the German chess league.

To evaluate the matter of player performance, meanwhile, the scholars used software programs that assess each move made in each chess match, identify optimal decisions, and flag significant errors.

During the tournaments, PM2.5 concentrations ranged from 14 to 70 micrograms per cubic meter of air, levels of exposure commonly found in cities in the U.S. and elsewhere. The researchers examined and ruled out alternate potential explanations for the dip in player performance, such as increased noise.

They also found that carbon dioxide and temperature changes did not correspond to performance changes. Using the standardized ratings chess players earn, the scholars also accounted for the quality of opponents each player faced.

The researchers also found that when air pollution was worse, chess players performed even more poorly when under time constraints. The tournament rules mandated that 40 moves had to be made within 110 minutes; for moves 31-40 in all the matches, an air pollution increase of 10 micrograms per cubic meter led to an increased probability of error of 3.2 percent, with the magnitude of those errors increasing by 17.3 percent.

“We find it interesting that those mistakes especially occur in the phase of the game where players are facing time pressure,” Palacios said. “When these players do not have the ability to compensate [for] lower cognitive performance with greater deliberation, [that] is where we are observing the largest impacts.

"You can live miles away and be affected. It’s not like you have to live next to a power plant,” Palacios added. "You can live miles away and be affected."

"There are more and more papers showing that there is a cost with air pollution, and there is a cost for more and more people," Palacios said. "And this is just one example showing that even for these very [excellent] chess players, who think they can beat everything—well, it seems that with air pollution, they have an enemy who harms them."

So when the Airthings Masters starts, and the commentators refer to Carlsen's air quality—remember he likes his environment warm and plays from Norway, which is renowned for clean air—there may be something in it.

If you are wondering how the air quality of the players is affecting their play, follow the move-by-move coverage of the Airthings Masters on Chess.com from February 6 through February 10.

Stay on top of indoor air quality with Wave Plus. Use code CHESSAIR for $100 off go.chess.com/airthings_us