Study: Chess Grandmasters Live Longer

Chess grandmasters tend to live longer than the general population. This is the conclusion of a study co-written by GM David Smerdon.

At 96, Yuri Averbakh (Russia) is the world's oldest living grandmaster. That title used to be held by Hungarian GM Andor Lilienthal (Hungary), who died in 2010 three days after turning 99. Obviously there are examples as well of grandmasters dying (too) young, such as Leonid Stein (Russia) and Vugar Gashimov (Azerbaijan).

Grandmasters seem to be like everyone else when it comes to life expectancy, right? Well, no, says a recently published study. They tend to live longer.

The peer-reviewed research article "Longevity of outstanding sporting achievers: Mind versus muscle," written by An Tran-Duy, GM David Smerdon and Philip Clarke, was published on May 3 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE. It examines the overall as well as regional survival of grandmasters in comparison the general population, and also puts them next to that of (athletic) Olympic medalists.

The researchers used data on 1,208 grandmasters and 15,157 Olympic medalists from 28 countries. The main results were (shortened from the original text):

- The survival rates of GMs at 30 and 60 years since GM title achievement were 87 percent and 15 percent, respectively.

- The life expectancy of GMs at the age of 30 years (which is near the average age when they attained a GM title) was 53.6 years, which is significantly greater than the overall weighted mean life expectancy of 45.9 years for the general population.

- Compared to Eastern Europe, GMs in North America and Western Europe had a longer lifespan.

- Both GMs and Olympic medalists had a significant survival advantage over the general population.

In short, grandmasters live up to 14 extra years compared to the general population; in regions such as Eastern Europe, where the overall life expectancy is lower, the difference is bigger than elsewhere, and the higher life expectancy of grandmasters is similar to that of top athletes.

"[This table] presents overall and regional life expectancy of a male GM who obtained the Grandmaster title in 2010 at an age in the range of 25–100 years, and life expectancy of the general male population matched by age and region. The overall life expectancy of GMs at the age of 30 years (which is near the average age when they attained a GM title) was 53.6 ([95% CI]: 47.7–58.5) years, which is significantly greater than the overall weighted mean life expectancy of 45.9 years for the general population. In all three regions, mean life expectancy of the GMs was longer than that of the matched general population, with gaps between them ranging from 1 to 14 years depending on age."

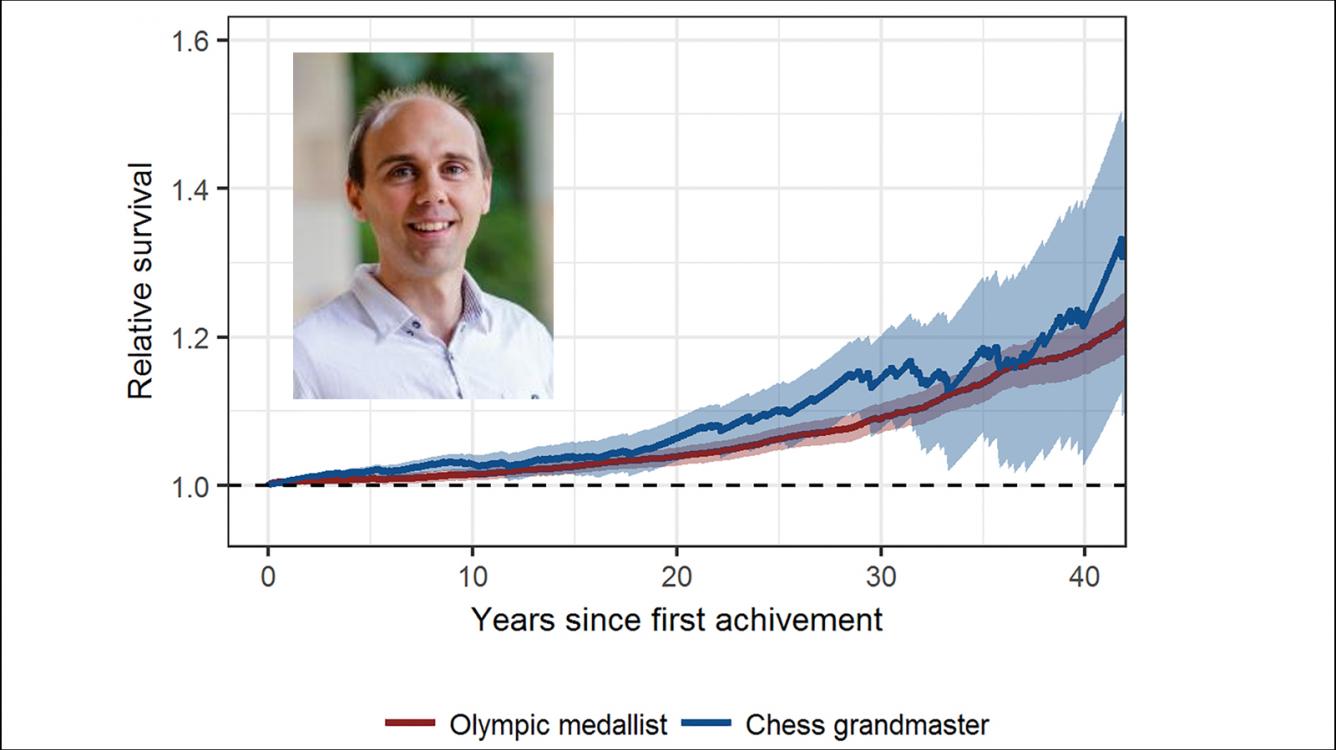

"[This figure] shows the survival of GMs and OMs from 28 countries relative to the general population from the same countries. Both GMs and OMs had a significant survival advantage over the general population. There was no statistically significant difference in the relative survival of GMs vs Olympic medalists."

The results are surprising, at least at first glance. Playing chess involves many hours of sitting, while one of the important aspects of living healthy is to move around regularly. Besides, aren't grandmasters known for their drinking habits?

Well, they used to, perhaps. The days of smoking at the board, and joining other grandmasters at the bar for a drink or two after the game, are long gone.

"Grandmasters live much healthier these days," co-author Smerdon told Chess.com. Maybe even healthier than average, he suggested as a possible explanation of the results. "We’re learning that taking care of your body helps the mind more." A Polish study confirms that chess players are in fact fitter than average.

Smerdon is a grandmaster himself, but a retired one. Last year, after spending many years playing (and starting his scientific career) in Europe, he returned to his home country Australia where he's now an Assistant Professor at the University of Queensland. His chess expertise obviously helped for this particular research.

"I'm only a small co-author here," he said. "When Philip Clarke and An Tran-Duy approached me for chess consulting, it turned out I could help them a bit more apart from collecting data."

Clarke, a big name in health economics, had found in earlier research that elite athletes engaged in physical sports have a significant lower rate of mortality compared with the general population. Then, he asked himself, what about mind sports?

A study from 1969 had suggested that professional chess players had shorter lifespans than amateur players with careers outside of chess. But the conclusion of this research, which involved just 32 players born before the 20th century, cannot be upheld anymore.

Besides reaching the conclusion that elite chess players live longer, it was also discovered that the life expectancy boost is rather similar to that of Olympic medalists. Whether you're spending your 10,000 hours on chess or on e.g. cycling, you're expected to live similarly longer.

"Follow-up research might focus on the reasons why," said Smerdon. "But that requires even more data such as the income of the family before and after someone becomes a GM, the general health plan, IQs, et cetera. It will be hard to get it off the ground."

Smerdon does plan to pursue more chess research in the future. "I want to focus on the positive side effects chess could have in poor communities, with kids who are not going to school, get ill or get into crime. I want to see if chess can boost their education attendance and other positive effects. Earlier studies have mostly focused on kids who are living comfortable lives."

We'll surely hear more from Smerdon, if only because his life expectancy should be decent. More decent than average.

Tran-Duy A, Smerdon DC, Clarke PM (2018) Longevity of outstanding sporting achievers: Mind versus muscle. PLoS ONE 13(5): e0196938.