The Grandmaster Who Faked His Title

The year was 1998. Anatoly Karpov defeated Viswanathan Anand in a controversial FIDE World Championship match, Nick DeFirmian won his third US Championship, and out of nowhere, a Grandmaster from Romania by the name Alexandru Crisan emerged with an incredible FIDE rating of 2635.

A rating of 2635 may not seem like much by modern standards, but remember, rating inflation was not as extensive back in 1998. In fact, such a rating would put him at 33rd in the world! However, his career at the top was short-lived due to what would go down as one of the most unique cheating cases of all time. This is the story of Alexandru Crisan — the fake chess Grandmaster.

The Beginning

Alexandru Crisan was born to unidentified parents on the 31st of July, 1962 in the small Romanian town of Simleu Silvaniei, a town in the Salaj County that is known for the Bathory Castle, Zoltan Fermati and... Crisan.

Picture of Simleu Silvaniei ©Simleu Silvaniei's Official Website

Little is known about Crisan's early life but the first recorded game was played in 1984 in round three of an unknown Bucharest tournament against 18-year-old soon-to-be Grandmaster Efstratios Grivas. Crisan, at the time, had already amassed an astonishing rating of 2310, legitimately or not, I don't know, but here's that game:

Anyone who has played club tournaments will know how stressful it is to face a strong player who defends stubbornly, which, in addition to the sharp nature and the time trouble that was likely present in the endgame, made it difficult to accurately guess the exact level the game was played at. However, if I were to take an educated guess, I would say that Crisan was at the level of an advanced club player, like that one guy at your local club who shows up every weekend and wins a couple hundred dollars every time, yfm?

Crisan's first tournament of note came a few years later in 1989 when he participated in the Dutch Open. The Dutch Open was nothing like the local Bucharest tournaments in terms of participants' skill levels, consisting of two Grandmasters, several International Masters and a fast-improving 17-year-old named Loek van Wely.

Our hero, Alexandru Crisan, did not attain a particularly desirable score, only winning two and drawing two of his nine rounds to end the tournament on a score of 3/9.

At this point, Crisan seemed like he would never be able to have his name remembered in the chess world, especially since he was already 27 and not pulling off upsets like a prodigy, but something would happen nobody would have expected.

The Cheating Case

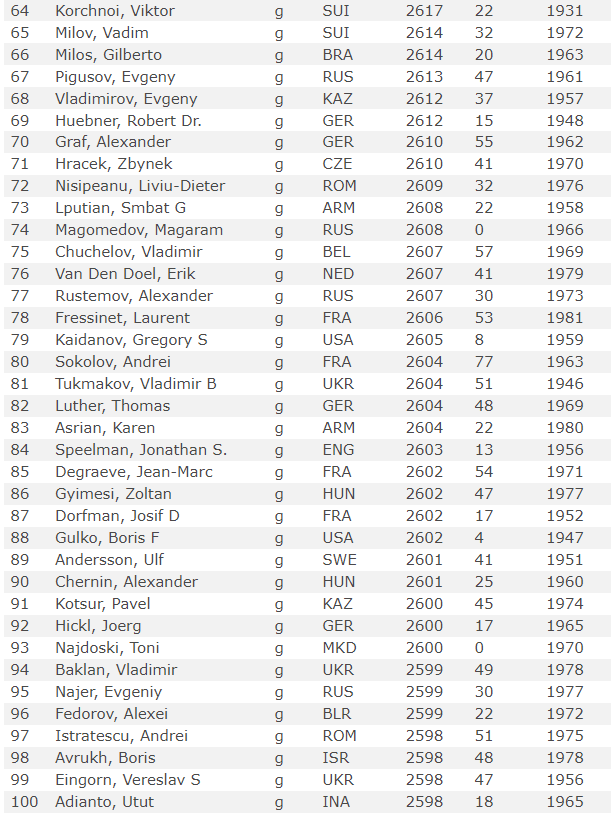

Throughout the 1990s, there was a very small amount of games played by Crisan. However, as indicated by his rating graph on ChessBase, he gained massive amounts of rating at a time, acquiring the title International Master in 1991 and Grandmaster two years later. By 1998, he had already reached a rating of 2635, which would have placed him at 33rd in the world if he wasn't inactive, ironically.

Alexandru Crisan's FIDE Rating Graph ©ChessBase

Grandmaster Michal Krasenkow wrote about this issue in the New In Chess Magazine:

....On the other hand, some of the names present in the list just bewilder. First of all, we see a new top player with an amazing 2635 rating Alexandru Crisan. One can hardly find any games of this guy in databases since 1989 (has rating of 1.1.1990 was 2235). I have taken the trouble to look at his recent results (thanks to the Internet rating database). These are near-100% scores in some Romanian tournaments one has never heard about.

Remarkably, Crisan did so without:

- Playing any games of note in the past 10 years against the top 10 players in his country

- Participating in the top group of the National Championship

- Representing his federation in any Chess Olympiad

- Having many games in the accessible database or otherwise published

- Any result coming from any official or well-established tournament in Romania or other places in the world

Initially, the matter was brought to FIDE by the Romanian Chess Federation. They pointed out that they had detected irregularities concerning some tournament rating reports. Additionally, the arbiters who were said to be in charge denied ever signing these reports, including the Troeful Sfinx, the tournament that supposedly brought Crisan to 2635, but there were no public records of this tournament ever occurring.

How shocking...

FIDE agreed to retract the 105 rating Crisan has gained in the Troeful Sfinx but did not interfere with anything else. At the time, the Romanian Chess Federation was even favouring sanctions against him.

Crisan responded by taking over the Romanian Chess Federation, appointing himself President of the federation and subsequently restoring his rating of 2635. He also suspended players Elisabeta Polihroniade and Andrei Istratescu and began billion lei defamation lawsuits against them (around $216 million USD today).

Backed up by the evidence provided by GM Krasenkow in the NIC magazine, FIDE decided to intervene in this matter. It was decided that Crisan was to verify his rating by playing in three tournaments selected by FIDE. The first of which was the 14th Milan Vidmar Memorial Tournament held in the coastal Slovenian city of Portoroz in 2001.

Results of the tournament ©The Chess Viking YouTube Channel

Crisan's result in the tournament was disastrous, only scoring 0.5 out of 9. Somehow he managed to draw a game against Adrian Mikhailchisin, who seemed to be in a somewhat of drawing mood, drawing all of his games. In most of his games, Crisan just got slaughtered, but there were some interesting ones.

It would be quite difficult to find a player incapable of playing 57...Rxe3 and 58...Ke5. Since white's king could not get in front of the pawn, it would be impossible to lose from there as black. Crisan must have been kicking himself for how that game panned out.

After his dreadful performance in the 2001 Vidmar Memorial tournament, the FIDE qualifications body decided to strip Crisan of his GM title, but before implementation, a quick phone call from a politician friend of Crisan to FIDE President Kirsan Ilyumzhinov saw the title restored and the rating adjusted to just below 2600, conveniently just outside the top 100.

Crisan's readjusted 2588 was just outside the top 100 in the July 2001 FIDE rankings ©ratings.fide.com

Crisan never played the rest of the three verification tournaments but one month after the Vidmar Memorial, he showed up in Klodovo. Surprisingly, in that tournament, he won! However, the way he did it was by making short draws on demand against most players and only winning games against some veterans from the former Yugoslavian Republic whom where able to throw their games, namely Dusan Rajkovic and Branimir Maksimovic, who had fallen on hard times since the Yugoslavian meltdown in the early 1990s.

Most of Crisan's draws lasted less than 20 moves. ©365chess.com

It was possible that those draws were legitimate as not many people have heard about Crisan yet so they might have thought that he was an actual 2588 rated player, or there might have been some bribery involved. In any case, those games weren't particularly interesting so I will only go through the ones against Rajkovic and Maksimovic.

Something I have noticed is that these games were going into very deep theory, so either Crisan spent a few weeks revising his lines on Chessable prior to the tournament, or there was some prearrangement involved. Maksimovic must have been chuckling to himself on move 23 when Crisan, not being the 2588 level player he claimed to be, was not able to discern the difference between the position in the 1985 Pinter - Olafsson game and the one on the board and tried to continue with the original plan of 23.Nxf7??. At risk of losing the game, Maksimovic had to find a creative way to throw, which he did with 24...Rc2??. There was another game against former Yugoslavian champion Dusan Rajkovic which was interesting.

All the draws plus the four wins he got from Maksimovic and Rajkovic made Crisan end the tournament on 7/10, tied first with Hungarian GM Robert Ruck, although when you look at their respective Wikipedia pages, the Klodovo win is on Ruck's page but not on Crisan's page.

The final results of the Klodovo tournament ©365chess.com

The last games played by Crisan were in the Danube Summer tournament in Tekija that same month. Like the Klodovo tournament, this one was also played in a double round-robin format but with only two other players, Dragoljub Jacimovic and Miroslav Markovic, who were both Grandmasters from the former Yugoslavian Republic.

In this tournament, Crisan scored 3.5/4, winning both of his games against Jacimovic and winning one and drawing one against Markovic while all the games played between the other two were drawn. This tournament had games that terminated a lot more suddenly than the ones in Klodovo, often ending when Crisan has an endgame advantage but the other player still has some chances.

To me, the resignation by Jacimovic seemed quite random. Sure he was down two pawns on the queenside, but he could have tried to create counterplay with ideas like bringing the king to g1 via e2 and f1, which you would expect a Grandmaster to at least attempt, but he didn't and just resigned. The other game against Jacimovic was also very fishy, to say the least.

For a Grandmaster, it should not have been hard to find a better continuation than 35.Qg3. Even a move like 35.h3 would have survived since black can't play Bxf1 without being checkmated by 36.Rd8+ Kh7 37.Qf5+ g6 38.Qxf7#. A move like Rc1 would have also been fine for white since Bxf1 fails, so black would have to resort to repeat moves from shuffling rooks back and forth. Taking this game, together all the other games into account, it is hard to say that the tournament was a legitimate one.

The final results of the Danube Summer tournament ©365chess.com

Aftermath and Legacy

Elisabeta Polihroniade confessed that she expected to be bankrupted by Crisan's lawsuits and political influence, but in 2002, she started turning the tables legally when Crisan came under the spotlight. In spite of that, it was not until 2010 that Crisan was sentenced to four years in prison for non-chess related corruption.

Despite FIDE trying to cover up their internal corruption by removing any records of the Klodovo and Danube Summer tournaments from Crisan's profile and making it seem like the rating was changed to 2132 after the Vidmar Memorial, it was not until August, 2015 when he was finally stripped of his undeserved GM title and his rating adjusted down.

FIDE tried to cover up their internal corruption ©ratings.fide.com

Crisan was not the only person who arranged titles for himself by playing in non-existent tournaments. GM Ian Rogers alleged that FIDE Vice-President and Russian chess federation President Andrei Makarov had arranged an IM title for himself.

In 2005 FIDE refused to ratify norms from the Alushta tournaments in Ukraine, claiming that the games did not meet ethical expectations despite the fact that a number of players involved protested. A different Ukrainian tournament in 2005 was found to be completely fake.

After the removal of Crisan's Grandmaster title in August, 2015, two other players, Gaioz Nigalidze and Igors Rausis, had their GM titles stripped — both for bathroom cheating.

Latvian-Czech Grandmaster Igors Rausis had his title stripped after being caught cheating in 2019

When Crisan's case was under investigation by FIDE, GM Zurab Azmaiparashvili, who at the time was one of the top players in the world, said after reviewing his games:

For me if I am asked how Mr. Crisan reached his rating of 2600, it is clear to me that it was done in an illegal way.

However, Azmaiparashvili himself was alleged to have also rigged the results of the 1995 Strumica Tournament to boost his rating. The tournament, in which he played 18 rounds against significantly weaker opponents, is generally regarded as an illegitimate event. In 2003, Evgeny Sveshnikov wrote:

The main problem is people surrounding Ilyumzhinov. The question begs itself: how many games one needs to buy and sell in order to become his assistant in FIDE or even FIDE Vice-President? Perhaps this sounds too harsh, but we see in his team such people as Crisan and Azmaiparashvili, who bought whole tournaments! This is an open secret and they don not deny it themselves. How is it possible that these people are in the leadership of FIDE?

Nowadays, prearranged results are still simply the reality of chess, according to Gregory Serper. Although Azmaiparashvili is still the President of the European Chess Union, there has been some improvement as neither current FIDE President Arkady Dvorkovich nor Deputy President Viswanathan Anand have a "Controversy" section on their respective Wikipedia pages.

So should the story of Alexandru Crisan's story be remembered as a cautionary tale for others to not repeat his actions, or were his actions undeserving of recognition? Tell me in the comments, I would like to know what you think ![]()

And of course as always, thanks for reading.