Chess Players Who Battled Depression

My forest is dark, the trees are sad, and the butterflies have broken wings.

Around 2 months ago, we observed the 32nd World Mental Health Day on the 10th of October 2023. It was first celebrated in 1992 at the initiative of the World Federation for Mental Health, a global mental health organization with members and contacts in more than 150 countries. It is celebrated with the overall objective of raising awareness about mental health issues and on this day, each year, thousands of supporters come to celebrate this annual awareness program to bring attention to mental illness.

Depression, the feeling of loneliness and hopelessness, is a worldwide issue faced by millions of individuals around the globe. Over 800,000 people die due to suicide every year. Michael Phelps, the most decorated Olympian who is widely regarded as one of the most accomplished athletes of all time, has been open about his struggles and battles with this medical condition.

In this blog, I will be trying to raise awareness about mental issues and that they happen on a much broader scale than most of us assume through this game of 64 squares. Chess, like any other competitive field, can be mentally demanding, and individuals may face various personal challenges. And so was definitely the case with the people I am writing about today. Many players and masters have their names registered on the dark page of the chess book which contains the list of those who battled mental health issues. Sometimes these issues resulted in tragic outcomes.

The exact cause of depression and mental illness is not exactly known, but chess might serve as a trigger. Tournament chess puts an enormous amount of strain on the nervous system. Of course, chess in itself cannot be responsible for mental illness if the person is prone to developing one. But chess history has been full of players who suffered from severe cases of depression or other mental illnesses and decided to end their lives prematurely.

Let's have a deep dive into the tragic tale of talented chess players who won the chess battle but got defeated by life.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Lembit Oll

- Curt Von Bardeleben

- Norman Von Lennep

- Pertti Poutiainen

- Georgy Ilivitsky

- Harry Nelson Pillsbury

- Alvis Vitolins and Karen Grigoryan

- Shankar Roy

- Dmitry Svetushkin

- FINAL THOUGHTS AND STATEMENTS

- CONCLUSION

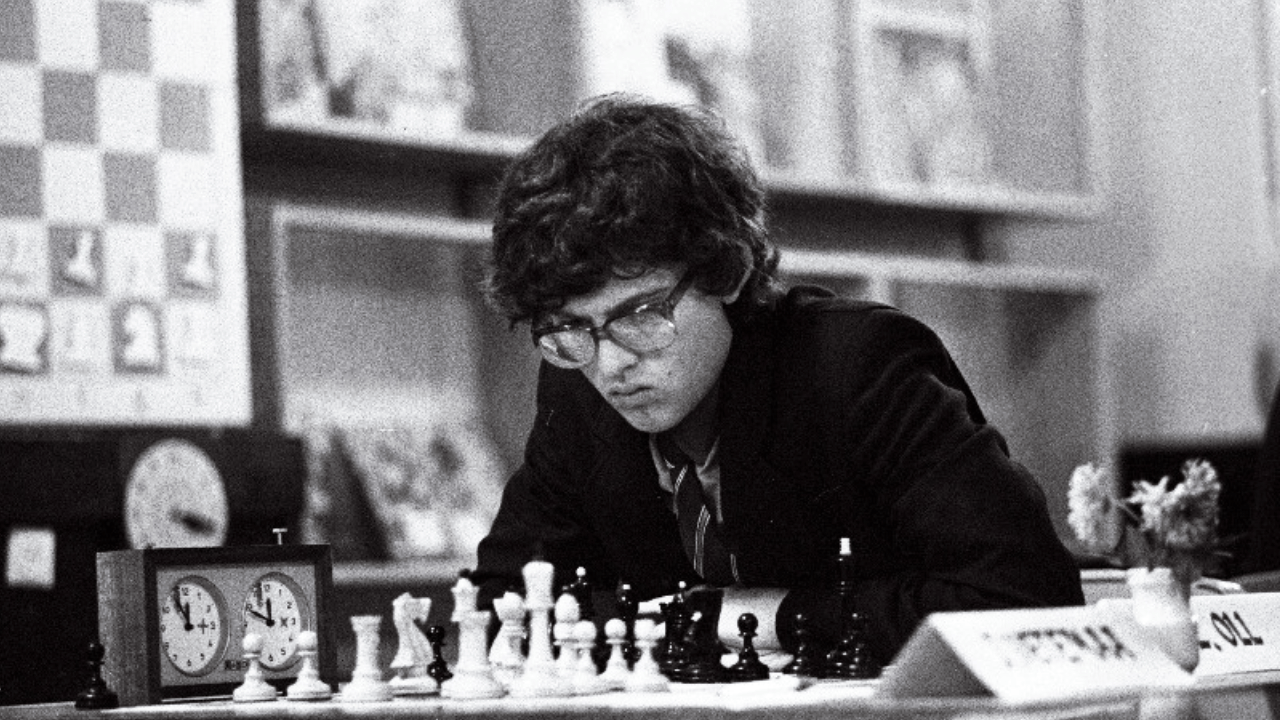

Lembit Oll (1966-1999) was an Estonian grandmaster, and unfortunately the highest-rated player on this list. Born in the city of Kohtla-Jarve, Oll started playing chess at an early age and was already successful as a junior. He showed tremendous skills and talent and at the mere age of 16, Oll was his country's chess champion. Two years later, by the time he was 18, he was the Soviet Union's Junior Chess Champion.

He was awarded the title of international master (IM) by FIDE in 1983 and the wait finally came to an end when he received his long-awaited grandmaster title in the year 1990. He didn't look back and became one of the major representatives of Estonia in Chess Olympiads and European Team Chess Championships in the first half of the 1990s. The leading Estonian GM at the time, he reached his peak rating of 2650 in July 1998 and attained 25th position on the FIDE rankings.

Things were looking good and it seemed like Oll, who was still in his early thirties, would go on to register his name as one of the finest Estonian chess players in history.

But things took a quick and tragic turn, as he fell into severe mental health issues after divorcing his wife in 1996 and losing the custody of his two sons. Although he was prescribed anti-depressants and received medication, the depth of the hole he discovered was too much for him. And the tragedy took place, as the tournament in Nova Gorica in 1999 where he shared second place turned out to be the last tournament of his life.

On 17 May 1999, he jumped out of the window on the fifth floor of his apartment in Tallinn and couldn't survive. He was just 33. He was buried in a cemetery that was not too far away from that of Paul Keres, the most famous Estonian chess player.

Curt Von Bardeleben (1861-1924) was born in Berlin and started playing chess when he was ten years old, quickly becoming one of the strongest players in Weimar. He studied law but never practiced, finding the lure of the chessboard too strong to resist. He was undoubtedly an extremely talented chess player, capable of first-class results, but his temperament was unsuited to the hurly-burly of tough competitive play, and its inevitable setbacks. He recorded some fine results during the 1880s and 1890s, but his best result occurred during the first half of the Hastings 1895.

This "1-0" at the end of the game requires some explanation. Bardeleben now saw the spectacular finish that awaited him and elected to "resign" by simply leaving the tournament hall and not coming back. Obviously, this is rather poor sportsmanship. After this devastating loss, he wanted to withdraw from the tournament. Ironically, this game is now virtually the only thing he is remembered for - perhaps the idea of gaining immortality as a loser is what upset him so much.

This game was a turning point for Bardeleben, who had a tremendous score of 7.5/9 up to that point, it marked the start of a collapse. He only managed 4/12 in the second half. Post 1895, he did win a few local tournaments, but the chess world never saw the old Bardeleben again.

Bardeleben was a charming old chap, but he lacked the will to win.

- Alexander Alekhine

After leaving the competitive chess window, he started working as a journalist and magazine editor. His life and death have been cited as the main inspiration for the main character in the novel The Defense ( or The Luzhin Defense) by Vladimir Nabokov. In 1924, at the age of 62, he committed suicide by jumping out a window, just like Nabokov's main character, Luzhin.

Try not to be too upset by a loss, setbacks are inevitable, and it is most useful to view each as a learning experience.

All of us know about Jorden Van Foreest, one of the most celebrated Dutch chess grandmasters of the 21st century. But how many of you know about the tragic story of one of his family members from the late 19th century?

Norman Von Lennep (1872-1897) was a talented Dutch chess player who was born into a wealthy family in the capital city of Amsterdam. He was a chess enthusiast from an early age but did not quite get the time to pursue the game as a child due to family pressure. He came from an upper-class family and was expected to study, earn a title, get a nice job, and get married. But instead, he chose to become a chess professional.

At the age of 20, he became a secretary of the Dutch Chess Federation and an editor of its magazine. He drew matches against players like Rudolf Loman and won a match against his family member Arnold Van Foreest (who is the great-great-grandfather of Jorden Van Foreest). He took 5th place at the Rotterdam 1894 tournament.

In August 1895, Lennep went to England and served as a journalist during the 1895 Hastings tournament and reported on the tournament for his magazine. Later on, it was announced that he had decided to stay in England.

However, not everything had been going well in this personal life. From his letters, it appeared that his father had disowned him and decided to exile him for his choices. It was only gonna end if he was to cease his involvement in chess and find a steady job.

Being abandoned by the family and living in a foreign country among strangers, nobody to care about, and no friends, apparently took its toll on his mental state. In 1897, he took a ship sailing from the English town of Harwich to the Hook of Holland. During the voyage, he shockingly ended his life at the mere age of 25 by jumping into the North Sea.

Pertti Poutiainen (1952-1978) was a strong international master and one of the top Finnish chess players. He was a two-time Finnish chess champion, winning gold medals twice at the Finnish Chess Championships in 1974 and 1976. In 1974, he represented Finland at the 21st Chess Olympiad, and in 1975, he participated in the FIDE Zonal tournament for the World Chess Championship. Pertti was awarded the title of international master by FIDE in 1976 and played for Finland multiple times in the Nordic Chess Cups.

Poutiainen was a talented player from Finland. He was their chess hope.

- Boris Gulko

However, it seemed like he was quite upset with his play and results. And the unexpected happened. Serious dysfunction and pursuit of game perfection led to the tragedy of this Finnish champion and he crumbled under the expectations and hopes. The stress of chess tournament life became too great for him and he took his life on June 11, 1978, at the young age of 26.

Virtually forgotten today, Georgy Ilivitsky (1921-1989) was born in Astana, the capital city of Kazakhstan, and was one of the strongest Soviet chess masters after the Second World War. Fascinated by the game of chess in his youth, he first came to prominence in the Trade Union Team Championship in 1946 where he showed great determination against Isaac Boleslavsky. At the time, his rating was estimated to be around 2100. Although he showed little regard for opening theory, he was an excellent positional and defensive player.

His major successes came after WW2. Working as an engineer at the Urul Engineering Works, he tied for first place in the Russian Federation Championship and won in 1949. He was awarded the IM title by FIDE in 1955, the year when he tied for 3rd place in the Soviet Championship along with Botvinnik, Petrosian, and Spassky, finishing ahead of players like Keres and Taimanov.

This tremendous performance qualified him for the 1955 Interzonal Tournament, where he missed the ticket to the Candidates Tournament by half a point.

However, he was unable to sustain himself at the very top of Soviet chess and was unable to make further progress. And the way the Soviet chess system was designed, life was tough for players who did not make it to the very top and did not get the opportunities to play outside the USSR. So was the case with Ilivitsky. This feeling of failure and abandonment haunted him for the rest of his life.

On November 28, 1989, he decided life had become unbearable and committed suicide by jumping out of the window.

This is an example of how merciless the Soviet system was. The top GMs enjoyed great privileges at the cost of everyone who couldn't make it to their level. Soviet chess was based on the idea of "Winner-takes-it-All".

Even though it did not have the worst consequence, the story of this American chess superstar is no less sad and tragic.

Harry Nelson Pillsbury (1872-1906) was a leading American chess player in the 1890s. Born in Somerville, Massachusetts, he started his career in the competitive chess window in the year 1888, and four years later, he beat Wilhelm Steinitz, the World Champion of the time by 2-1 in an odds match.

Pillsbury shot to fame when he won his first major tournament. No one had ever done this before and only Capablanca later achieved a success of similar magnitude on his international debut. Although considered merely an outside bet for Hastings International in 1895, Pillsbury produced some magnificent chess, scoring fifteen wins, three draws, and only three losses. He finished ahead of top-class players like Steinitz, Chigorin, Tarrasch, and the World Champion of the time, Lasker.

The result at Hastings 1895 carried Pillsbury to the top of the chess world. He continued his exceptional form in the first half of the Saint Petersburg tournament, a round-robin tournament with Lasker, Steinitz, and Chigorin. After nine rounds Pillsbury was a clear leader with 6.5 points. However, his play mysteriously collapsed in the second half, when he could muster only 1.5 points, leaving him in third place. He won the US Chess Championship in 1897, a title which he held till 1906.

Pillsbury possessed unparalleled technique when it came to unleashing the explosive powers of his pieces.

- Max Euwe

Pillsbury caught syphilis at St Petersburg, which plagued him for the rest of his career. Poor mental and physical health led to his ultimate demise, preventing what could have been a legendary career. After he was hospitalized in 1905, contemporary newspapers described him as "temporarily insane". He attempted suicide from the fourth floor of the hospital where he was being treated for mental disorders. He died in the year 1906, at the age of 34.

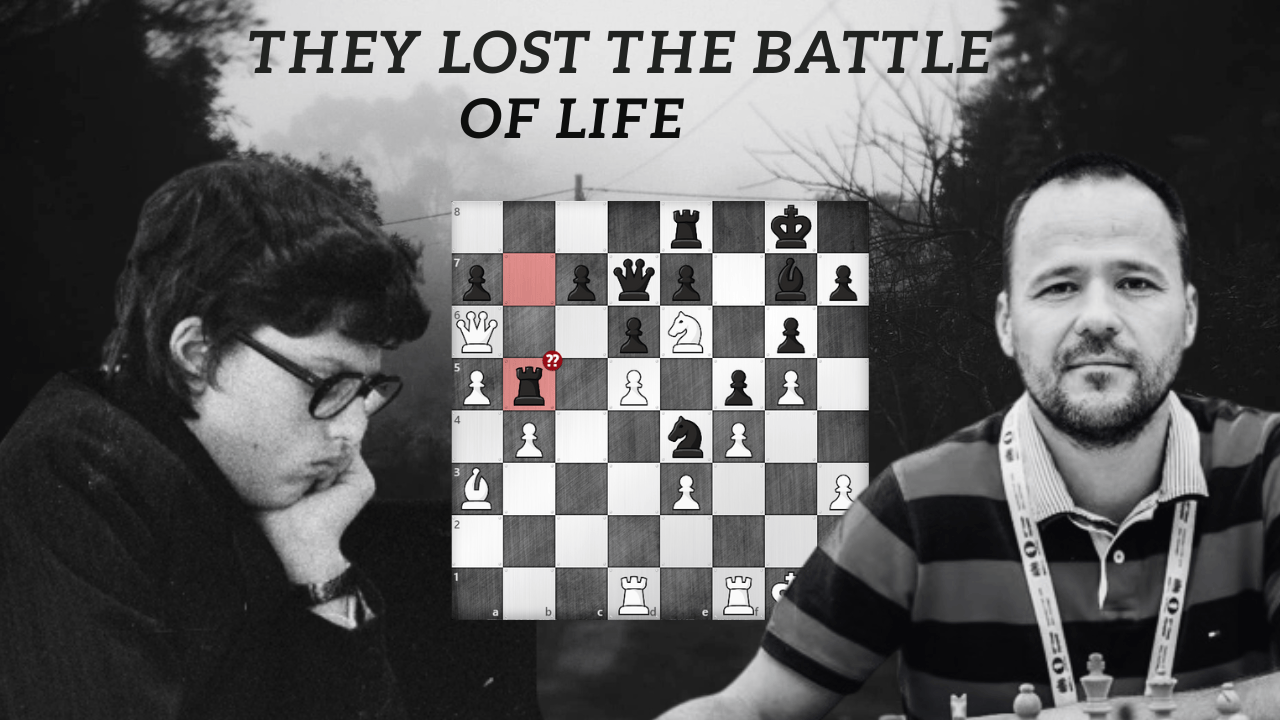

Alvis Vitolins and Karen Grigoryan

Birds of a feather flock together.

- Somebody wise

This is the tragic tale of two really close friends who decided to end their lives prematurely.

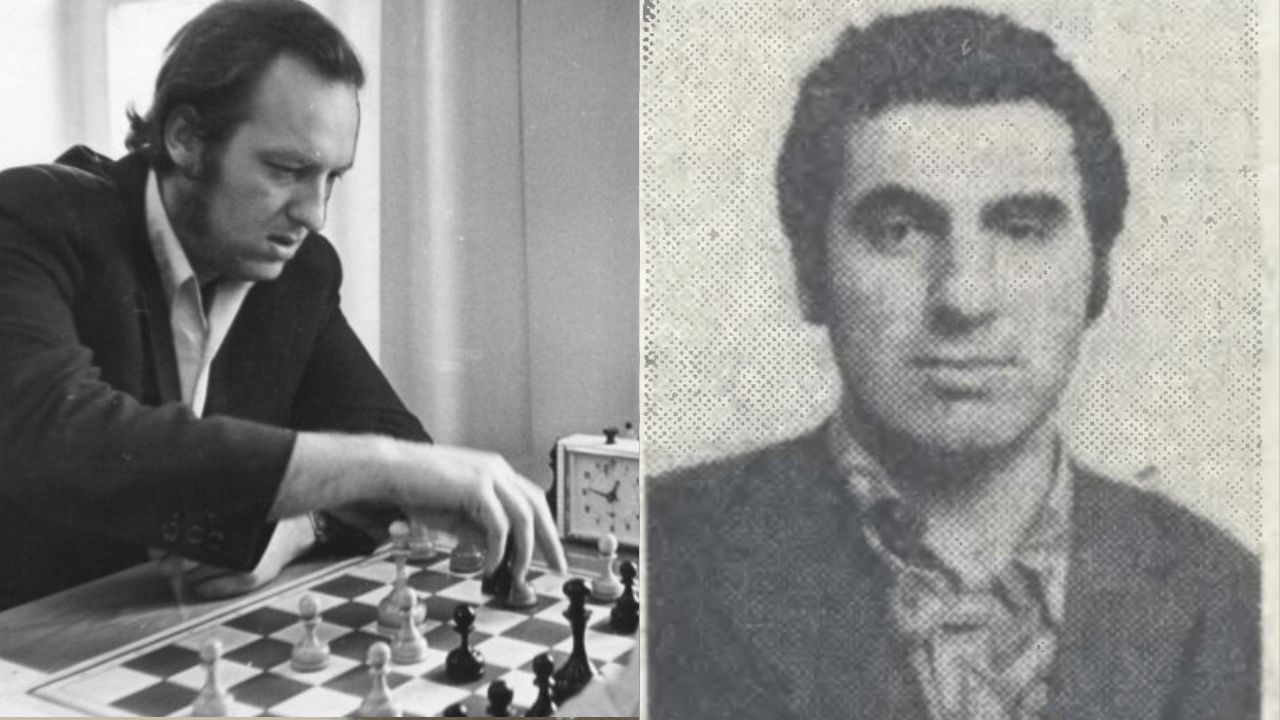

Alvis Vitolins (1946-1997) was a Latvian chess master who won the Latvian Championship in 1973, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1982, 1983, and 1985. He was an extremely promising player in his youth and was also Mikhail Tal's training partner. He was awarded the international master title in 1980 and was an opening theoretician, with many lines bearing his name in the Sicilian Defense.

However, he failed to realize his own potential.

Vitolins suffered from severe mental dearrangement. Effectively from the very start, he was not so much battling against his opponent as against himself.

- Gennadi Sosonko

The decade of the 1990s was extremely tragic for him. His parents died within the space of one week, and the psychiatrist who had been treating him also died. Even though he was prescribed anti-depressants, he couldn't bear the pain and felt that he was no longer needed by anyone. On 16th Feb 1997, he threw himself onto the ice from a railway bridge spanning the Gauja River.

Karen Grigoryan (1947-1989) was an Armenian chess master. Born in Moscow, he was one of the best Armenian players of his time and is a 3 time Armenian Chess Champion. He was awarded the title of international master in 1982, but not before winning the Moscow City Chess Championship twice in 1975 and 1979. He participated in the USSR Chess Championship several times with his best performance being at the one in 1973, where he finished at 7th-8th place.

But his success at the chessboard didn't last long. He had been battling depression all his life, and this struggle came to an end when he took his life by jumping from the highest bridge in Yerevan on 30th October 1989.

Incidentally, Vitolins and Grigoryan were close friends and could often be seen together at tournament halls. They both were excellent blitz players but also suffered from psychiatric disorders.

The friendship between Grigorian and Vitolins was not a friendship in the generally accepted sense of the world. Shut off from the other world, they simply understood each other, or, more correctly, trusted each other.

As they say, birds of a feather flock together....

One of the most recent, but no less tragic is the story of one of the brightest chess talents of West Bengal chess, IM Shankar Roy (1976-2012). He started playing chess when he was eight years old under the guidance of his father. One day, he beat his father comprehensively in this game of 64 squares. From that day onwards, he started concentrating on chess.

He improved quickly and became a professional chess player. An employee of the Eastern Railway, Roy represented India in several international tournaments in countries like Germany, Singapore, Romania, and Brazil. An extremely talented player, he won the senior state championship four years in a row from 1995.

Roy had been suffering from depression for several years, though he slipped into severe depression after the death of his father. He made a suicide attempt and was found hanging from the ceiling of a ground-floor room where he used to practice the game. A suicide note found on the table said he was going "in search of god". His father was like a god to him.

And the final name on the list, we have the tragedy of arguably one of the greatest Moldovan chess players ever, Dmitry Svetushkin. Svetushkin (1980-2020) learned how to play chess at an early age, and quickly began professional chess training under the guidance of Vjacheslav Chebanenko, a very well-known theoretician and trainer. He was awarded the international master title in 1997 and the grandmaster title in 2002, at the age of 20. Two years prior, he won the Moldovan national championship in 2000.

Svetushkin took part in team championships in various countries and was known for his solid and impeccable positional style and endgame technique. Between 2000 and 2018, he represented his country at ten chess olympiads and became an official FIDE trainer in 2014, following the footsteps of his idol Chebanenko. In the 41st Chess Olympiad in 2014, he put up a performance rating of 2809, the fourth best on board two.

Apart from chess, he shared diverse interests in Russian Literature, Jewish metaphysics, and Ironman triathlons.

Svetushkin did a lot to help and train young talents in Moldova. With a peak rating of 2621, he was a familiar figure in chess, but he was much more than that. His friends described him as a very humble, friendly, well-read and versatile person. But was all actually well with him? This question comes to mind because, on the 4th of September, 2020, Svetushkin committed suicide by jumping out of a window from the 6th floor of a building. He was just 40 years old.

There was no suicide note, nothing to explain this sudden departure from life. I spoke to him just the day before on Skype, from Israel – he looked refreshed, joked, laughed, discussed the works of Dovlatov, who he’d become interested in, and was planning to study chess with me in a couple of days. “Make sure to call me when you play in the league at the weekend, ok?” he asked me. I couldn’t keep the promise. Dima committed suicide while I was still playing, and I still can’t shake the thought that if I’d finished playing an hour earlier and phoned immediately then perhaps the tragedy wouldn’t have happened. Perhaps someone just had to be there at the right time at the onset of depression and that would have held him back?

- Israeli Grandmaster Ilia Smirin

Ilia Smirin further went on to say that Svetushkin was personally unsettled according to him. Smirin said that he lacked those qualities without which, professional chess is tough. He lacked those killer instincts. He was hopelessly kind and indulgent, too generous.

Maybe we were unaware of something important about the grandmaster. He was a figure of kindness, but that's what hindered him in his chess life. The unexpected had happened, the passing away of this chess player had shuddered the chess world.

Is life too random a thing?

- GM Murtas Kazhgaleyev on Svetushkin's death.

Mental health issues are very abundant today, and recently they have been on the rise. And these were the tragic stories of those players who couldn't win this battle of life and lost. Chess, our game, has been the game of those creative geniuses who left an unerasable mark on the chessboard, but sometimes the situation just worsens and worsens.

Giving a pause to this post, I would like to say that some people really need help. Show those people that you care about them, especially those who need someone to care about them the most. Even the smallest of tries from us, the chess players can change someone's life. Create supportive communities, promote mental health in chess education, and participate in campaigns. Because you never know, you might save someone's life.

Thanks for reading, I hope I was successful at least a bit in what I had intended before starting to write the post. I am open to all sorts of feedback, whether positive or negative, so do share them if you have some.

Here are the sources used for writing the blog: Wikipedia, Chessentials' article, Chess24's article, and Tartajubow's blog.

Once again, thanks for reading, and until next time, I am outta here.

Chess doesn't drive people mad. In fact, it keeps mad people sane.

- Bill Hartston