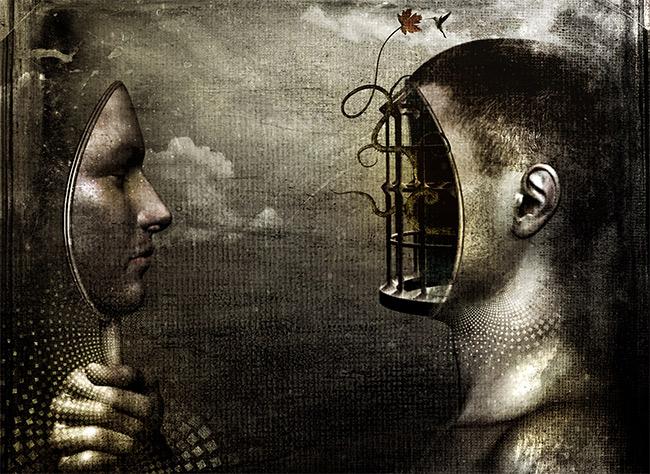

The Struggle With Yourself

Chess psychology is not just about selecting opening variations that will psych out your opponent, it's also about mastering yourself. Some players can just sit and calculate without emotion at the chessboard, but I'm not one of them. I feel ecstatic if I have a crushing position, and despondent if things are crashing down around my ears.

This may seem wholly bad, but it is a double-edged sword. When I'm winning, the opponent may pick up on my confidence and lose some of their own, though it means I'm also less likely to buckle down and crunch the variations to reel in the point. When I'm upset about losing, I might miss some obvious saving resource, but caring so much has also motivated me to fight on and even win from a lot of crummy-looking positions.

Take this game against my (friendly) nemesis Jack, a talented young player whose style is quickly maturing. He's an aficionado of the Accelerated Dragon so I didn't want to play into a mainline Sicilian. I prepared a Bb5 Sicilian/Grand Prix hybrid, a positional attacking variation in which Black doesn't get much counterplay - perfect for making a Dragon-rider uncomfortable:

After only 15 moves, the game is basically over. Jack's only chance is to draw me into some sort of unclear tactical melee, and with shrewd psychology, he succeeds:

Soon I was down a piece and could have justifiably resigned. Luckily, though, I ploughed on and found some hidden chances, even clawing my way back to a winning position at one point (QQ vs QR...don't ask) but managing to blow it and allow a draw. I can't say I'm upset with that result, as it seems like a fair end to such an insane roller-coaster of a game. If I hadn't let emotions control me when I achieved a winning position, I would probably have won the game easily. Then again, I wouldn't have fought on to claim the draw if I'd acted rationally and just resigned when things went pear-shaped.

What can we conclude about emotions at the chessboard? They're neither good nor bad. Sometimes they help, sometimes they hinder. What's most important is that you control them - or at least harness them - or at the very least, be aware of them.