The History of Computer Chess - Part 1 - The 'Mechanical' Turk

Welcome to the first installment of my new series on the history of computer chess. I'll be looking at pivotal moments or figures in the history of chess and computers across ten posts; ten videos with analysis of important or interesting games, and ten accompanying blog posts that will delve into the history and context more closely.

In 1997, the world was poised in anticipation to see how a supercomputer would once again fare against the world famous chess champion in a second six game match. Deep Blue, a computer owned and developed by IBM, was to go head to head against Gary Kasparov, the long-reigning world chess champion and arguably the strongest player in the history of chess to date. Deep Blue’s shock win over the world champion was unanticipated, and taken to become known as a symbolically significant event in the history of man versus machine. If a computer can beat the best chess player, a game we hold with such revere and consider mastery of such to put one firmly in the upper echelons of intelligence, then should we take this as a sign of artificial intelligence catching up to that of the human?

Later academic thought in computer science and philosophy downplayed the win, owing to human error in form of nerves and frustration on Kasparov’s part, and the nature in which Deep Blue operated; it was, after all, merely a computer processing billions of continuations per second, playing aggressively with brute force. Yet in 2016, DeepMind’s artificial intelligence program AlphaGo convincingly beat the World Go Champion Lee Se-dol in a six game match, a feat not considered possible for at least another decade or so, if at all, due to the complexity and staggeringly large possibilities of continuations of Go in comparison to chess (the number of legal positions on a standard board in calculated to be in excess of the number of atoms in the observable universe).

Worldwide media and academic attention followed, as it seems that this is truly the benchmark event humanity has been waiting for; has a form of artificial intelligence surpassed that of the human, and more importantly, should we be afraid?

Deep Blue was not the first artificial intelligence to take on the great game on chess. The first figure I want to explore is a controversial one, 'The Mechanical Turk'. Not a computer as such, this automaton had a little help from human hands and minds alike, but made a big impact in Europe where its popularity enabled a series of owners and operators to tour for nearly a century.

The Turk was built in the 18th century at what is considered the beginning of the 'Age of Enlightenment', which began our early relationship with robots and artificial intelligence. Machines made in our image were developed in the period of change from natural to mechanistic philosophy, a time of rapid change in which our conception of self and society became increasingly more mechanised as technology developed. Throughout, we find a shift in our anxiety and perception of machines and self; from the curiosity and entertainment we garnered from the intricate and delicate automata of the 18th Century, to the dependence of the faceless and efficient machines of the Industrial Revolution, to our continued reliance on the supercomputers that now live in our own homes and, occasionally, beat us on the chessboard!

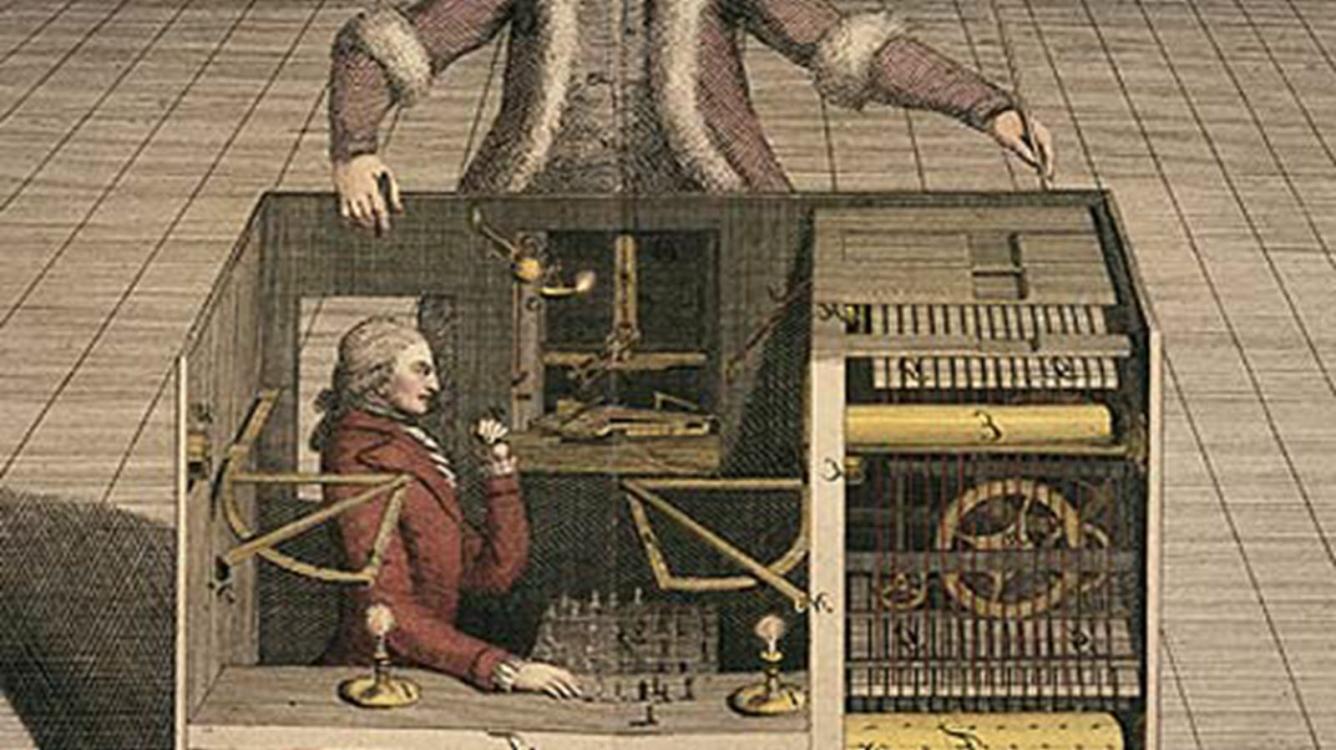

Built in 1770 by Hungarian creator Wolfgang van Kempelen, the Mechanical Turk, a chess playing automaton, appeared to herald the arrival of artificial intelligence itself. Comprised of a large ornate cabinet with sliding doors to reveal the inner cogs and wheels of the clockwork machinery that controlled the automaton player, across the top a chessboard in which in front sat The Turk, a life-size wooden automaton taking on the image of a European’s idea of a Turkish sorcerer, bearded and adorned with fur.

On The Turk’s 70 year tour of Europe and America, audiences and chess players themselves were thrilled and filled with fear as the machine proved itself capable of beating chess master after master, and some well known European leaders and academics alike. It was later revealed that The Turk was a hoax; a hidden partition of the cabinet obscured a series of for-hire chess player with the ability to manoeuvre the levers of the automaton, and play the game to a human ability.

The Turk was significant in that its design and purpose evolved from representation to simulation of the human form and human activities. Automaton, which are both alive and yet have always been dead, made in our image and form must mimic the activities we consider most human to complete their imitation. Huyssen commentates, “It is no coincidence that in the Enlightenment age literally hundreds of mechanics attempted to construct human automata who could walk and dance, draw and sing, play the flute or the piano, and whose performance became a major attraction in the courts and cities of 18th-Century Europe” (Huyssen, 1982, p.224-225). As humans we hold activities such as chess and structured music composition (before the advent of electronic programming) to be activities unique to humanity, as both the inventors and sole species to take partake in such.

Though the earlier man-made mechanical objects of the Renaissance and Medieval period were similarly designed in the shape or form of man, they were seen as products of magic, supposedly the creations of “…philosophers, priests and magi: men who can manipulate celestial forces, use the hidden properties of natural objects, and call on demons to create and control artificial copies of natural forms” (Truitt, 2015, p.40).

The automatons of the 18th Century were also quaint and ornate in appearance, and performed similar tasks or activities; to dance and sing, smoke a pipe, to handwrite notes of apparent sentience; however with the exception of the hoax of The Turk, the automatons were designed and consumed not to conjure feelings of awe in the divine, but to relish in the power of humans to master nature, to celebrate our developing technical skills and further our new direction in rationality above all else, though it is difficult to ascertain whether these design goals translated or reverberated through to the mass public audience that the touring automata attracted!

From objects of curiosity and entertainment, to tools and machines, to supercomputers that digitalise our daily lives, change the way we work and challenge the limits of our intelligence, artificial machines have developed significantly since the automata of the Enlightenment. They have challenged our concept of what it is to be human; biologically, socially, and philosophically. Advances in medicine mean that we may no longer blink an eyelid at Descartes’ concept of the Cartesian body as a machine; yet as our dependence on machines as tools continues, the idea that we are becoming increasingly automated both socially and functionally resonates to this day. The Mechanical Turk may have been a clever hoax, but it should be viewed as much more than an antique curiosity. It is an object of an era that shows that the line between man and machine has been blurred not merely for decades but centuries.

We will look at the next stage of computer development in a blog post soon. Please do also note that this blog post will also have an accompanying video on my YouTube channel very soon - www.youtube.com/c/gingergm

Charlie the Chess Cat - https://www.facebook.com/CharlieChessCat/ - helped me with the writing of this article.

References:

Huyssen, A. (1982) Vamp and The Machine. New German Critique. [Online]. Volume 24/25. Available at http://astro.temple.edu/~dmg33/Maker_files/huyssen.pdf [Accessed online 1st May 2019].

Truitt, E.R. (2015). Medieval Robots: Mechanism, Magic, Nature and Art. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.