Shōgi (将棋), occasionally known in the West as chess

Shōgi (将棋), occasionally known in the West as Japanese chess, is a two-player strategy board game belonging to the same family as chess and xiangqi, all descended from the Indian game chaturanga or some other type of relative. of close play.6The word shōgi is composed of the characters for general (shō 将) and board game (gi 棋), so it can be roughly translated as general's chess (or generals).

Shōgi was the first chess-type board game in history to allow captured pieces to be returned to the board by the player who captured them. It is speculated that this re-entry rule was invented around the 15th century and that it is probably linked to the practice among mercenaries of that century of changing sides when captured, a fate they considered preferable to being executed.

The game's oldest predecessor, chaturanga, originated in India in the 6th century, and the game probably arrived in Japan from China or Korea at some point after the Nara period. Shōgi in its current form was played as early as the 16th century, although a direct ancestor that did not include the re-entry rule is mentioned in a historical document Nichūreki of 1210, an edited copy of the Shōchūreki and Kaichūreki of the late Heian period (c . 1120).

History

According to Yoshinori Kimura, a professional player and who was for many years the director of the shōgi museum in Osaka, the distinctive features of shōgi with respect to other versions of chess in terms of rules, number, shape and name of the pieces and board, gave origin to the belief among some Japanese that it was an indigenously Japanese game.7 However, Kimura suggested that existing evidence suggests that shōgi is in fact a development of a game derived from an early version of Indian chaturanga and that it probably arrived to Japan from China, at which point the game began to evolve in different directions for several centuries in the two countries, concluding with shōgi in Japan and xiangqi in China.7

One of the clues to the presence of chess variants in Japan was the discovery of 16 wooden pieces similar to the current pieces, which were found in Nara Prefecture, in the Kōfuku-ji temple.7 The pieces have been dated around the year 1058 AD. C., and according to Kimura it is feasible that the game arrived about four centuries ago.7 According to Kimura, the intermediate point between the original form of the game and its current form occurred around the beginning of the 9th century, a point at which it is already known. They had established the movements of the pieces and some modern rules. This intermediate point is called Heian shōgi (as it existed during the Heian period [794-1185]).7 The Nichūreki dictionary of popular culture describes two types of shōgi: the dai shōgi and the shō shōgi, currently called Heian and Heian dai shogi. The current game is based on Heian shōgi. The researcher at the Nara Prefectural Institute of Archeology, Kōji Shimizu, mentioned that the Heian shōgi pieces are the same as the chaturanga game but with a special addition related to Buddhist symbolism (jade, gold, incense, silver, etc.). 8

According to Kimura, all the distinctive features of contemporary shōgi had already been established by the 13th century, two hundred years after xiangqi and two hundred years before Western chess.7 The game apparently gained popularity among the nobility in the centuries following, particularly in their versions with smaller boards and fewer pieces.

Shōgi players in Japan (1916–1918).

In the Edo period (1603-1868), variants of the game grew, and tenjiku, dai dai, maka dai dai, tai, and taikyoku shōgi emerged. Both the traditional game and Go were popular in the Tokugawa shogunate, who decided to grant a stipend (albeit a small one) to four exceptionally talented go and shōgi masters. According to Kimura, when the capital was moved to Edo (present-day Tokyo) these eight players acquired a status equivalent to that of gokenin (low-ranking vassals of the shogun), which began a hereditary system of grandmasters (iemoto) in the two games, teachers who earned their income primarily by teaching classes in the style of play of their particular school.7 Thanks to this system, go and shōgi schools proliferated with distinctive styles that led to modern styles. This iemoto system, however, collapsed with the fall of the shogunate in 1868 and the beginning of the Meiji Restoration, which meant that the iemotos lost their stipends and official status, combined with a decline in the popularity of games during these turbulent years.

Around the year 1899, the history of the games and movement began to be published in newspapers.

s of the game. This fact would contribute enormously to the development of the current system of professional gaming, as writing columns about shōgi began to be a well-paid job, giving players the possibility of earning a living.7 These were therefore the first professional players. The newspaper columns also resulted in an increase in the popularity of shōgi among the public and an increase in the quality of the game, as masters were able to charge higher rates for their articles.7 This also led to several players leaving. joined in alliances to get their games published. In 1924, the Tokyo Shōgi Association was founded, the original version of the current Japanese Shōgi Association.9

In 1937 professional player Yoshio Kimura became the first winner of the "Meijin" title using the Meijin-sen system. At the end of World War II, the US-led occupation government attempted to eliminate all factors they considered "feudal" in Japanese society. Shōgi was one of those considered to be eliminated, along with the bushido philosophy. The occupation government mentioned that the reason for eliminating the board game was that it promoted the idea of abuse towards prisoners. Kozo Masuda, one of the professional players of the time, insisted that the game did not encourage abuse, and instead said that Western chess allows the opponent's pieces to be killed without the possibility of giving them the opportunity to return them to the game.8 With this idea by Kozo Masuda the game was not banned during the American occupation.10

Description

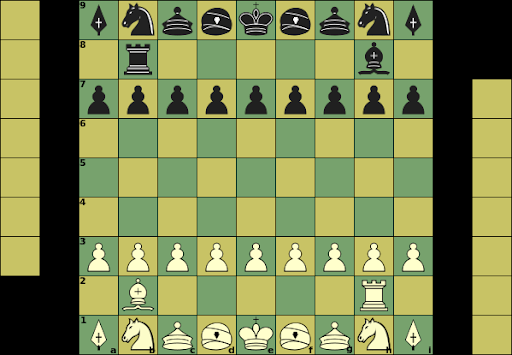

Shōgi is played on a board with 9 rows by 9 columns, with squares of the same color. Each player has 20 pieces equal to those of the other participant. The pieces are flat tablets slightly sharper at the front and have their name inscribed in Japanese ideograms. The two players' pieces are identical and only differ in the direction in which they point on the board. This allows the captured pieces to be used by the capturer in subsequent turns, one of the most notable features of the game compared to chess and xiangqi. Although there are Westernized Shōgi boards, with symbols on the pieces similar to those with which Western chess players are more familiar, these are not very popular, and the tendency is to usually play with a board and pieces with Japanese ideograms.

As in chess, xiangqi, janggi or makruk, the objective of the game is to capture the opponent's king, and as in those, checkmate occurs when the king is in a position from which he cannot avoid being captured. Having evolved from chaturanga, some of its pieces retain similarities with those of chess, but having evolved independently, shōgi includes some pieces that do not exist in chess, while lacking an equivalent to the queen. Likewise, some of its pieces' movements are more restricted than those of their Western chess counterparts (e.g., pieces that cannot move back). Since most of the resources on the game available outside of Japan have been translated into English, the nomenclature used in that language is almost universally used outside of the eastern country.

Parts

Shōgi shares pieces such as pawns, rook and bishop with chess, although each player only has one of each of the last two. It also has horses, although its movements are much more limited than those of chess. It also includes three pieces that do not exist in chess: the spear (lancer) and two types of generals (gold and silver generals) whose movements are similar to those of the king, although more restricted. There is no equivalent to the lady in shōgi.

The 20 pieces/tokens per side are as follows:

1 King (玉/王) (Placed in the center of the first [horizontal] row closest to the player.)

2 Golden Generals (金) (On both sides of the king).

2 Silver Generals (銀) (Next to the gold generals).

2 Horses (桂) (Next to the silver generals).

2 Lancers or Lancers (香) (Next to the knights, at the ends).

1 Bishop (角) (In the second row, on the left knight).

1 Rook (飛) (In the second row, on the right horse).

9 Pawns (步) (all in the squares of the third row, closest to the opponent).

In this way, the board diagram looks like this: (Above is the Ōshō—king of white—, and below is Gyokushou—king