A Brief History of Chess

Origin

Chess was borne out of the Indian game chaturanga before the 600s AD. Once it reached Western Europe, it evolved by the 1500s into what we now know as chess. One of the first masters of the game as we play it today was a Spanish priest named Ruy Lopez, from Segura, who did not invent the opening named after him, but analyzed it in a book he published in 1561. Chess theory was so primitive back then that Lopez advocated the strategy of playing with the Sun in one's opponent's eyes. Fun fact: Until about 1610, if your opponent placed your uncastled king in check, you lost the right to castle for the rest of the game, whether or not you had moved your king or corresponding rook.

Theory Through Morphy

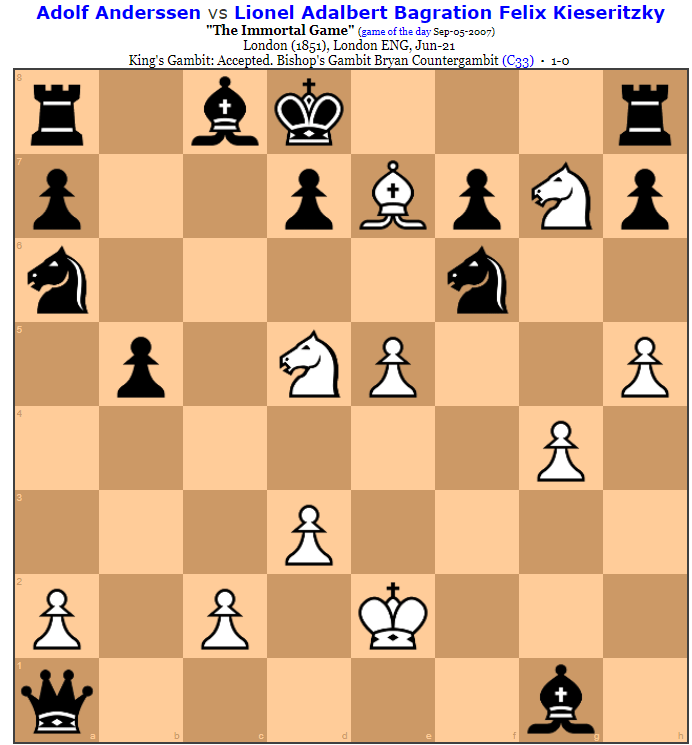

The Final Position of the Immortal Game

The Final Position of the Immortal Game

Until Wilhelm Steinitz became the first official World Champion, the game was played in an extremely aggressive tactical manner, unsimilar to today's strategies. This was because the game was thought of as the darling of the Romantics and if you weren't sacrificing your pieces right and left trying to checkmate your opponent in a violent manner, you weren't impressing the ladies. During the 1800s, the King's Gambit, rarely seen in top level play today, was all the rage, and Adolf Anderssen won some truly brilliant victories on either side of it.

Then Morphy showed up on the European chess scene, where the game was much more popular than in North America, and he soundly trounced every major player in the world except Howard Staunton, who was more or less past his prime and didn't accept Morphy's challenge. Morphy steamrolled Anderssen, Louis Paulsen, Daniel Harrwitz, and a host of other masters. Bobby Fischer, in the 1960s, ranked Morphy as the greatest player in history, an opinion not shared by many then or today. Fun fact: Fischer omitted Dr. Emanuel Lasker, World Champion for a record 27 years, from his list, probably because Lasker was Jewish and Fischer was quite the anti-Semite. His top ten list is not highly regarded today.

Staunton invented the form of the chess pieces as we know them best. Before he did, the pieces took all sorts of shapes, like men riding horses, and they were difficult to distinguish from one another on the board.

Steinitz and the Advent of Positional Chess

Steinitz never played Morphy, who had retired from the game by the time Steinitz rose to European prominence. Steinitz's theories about the game are still widely felt today, especially his disdain for aggressive, tactical play. he preferred to accept the popularly offered gambit pawn and then close the position down and grind out a win in a more methodical, quiet manner. We call this "positional" chess, as opposed to "tactical." Steinitz initially had no equal in this kind of play and, in 1886, won the first official world championship in a match against Johannes Zukertort. He held the championship until 1894, when Emanuel Lasker showed up and soundly defeated him, ten wins to five losses. Their rematch, 3 years later, was even more lopsided: Lasker won ten and lost only two. Fun fact: there was no global governing body in these days, controlling chess and deciding who got to play the world champion next. The champion himself decided based subjectively on who he thought was most deserving of a match. FIDE did not exist until 1924.

Positional chess as Steinitz and Lasker displayed now became more and more popular and the world's best players began experimenting with new openings, opening strategies, and not so often gambiting away pawns for attacking chances.

Hypermodernism

The prevailing theory until about the 1920s was to occupy the center of the board during the opening, usually with pawns. The most common openings were the Ruy Lopez, the Giuoco Piano, the Queen's Gambit (which really doesn't play out like a true gambit), the French Defense, the Four Knights' Game. These are relatively quiet openings from which both sides slowly try to accumulate small advantages in space and key squares, diagonals and files.

Jose Raul Capablanca defeated Lasker 27 years after the latter defeated Steinitz, and Capablanca's play was and remains the absolute epitome of simple, clear-cut positional mastery. He tended to avoid complex tactical situations, and instead would seize a seemingly small advantage out of the opening or middle game, then quickly convert it to a win in the endgame. His endgame skill was the greatest in the world up to that time. Even today, the best computers find very few errors in the way Capablanca played.

Hypermodernism showed up in the games and theories primarily of Aron Nimzovich, but also Richard Reti, Efim Bogolyubov, and Ernst Grunfeld. They advocated the idea of controlling the center with the minor pieces instead of merely occupying it with pawns. In this period, new openings were developed to purse this idea, like the Indian Defenses, the Grunfeld, the Benoni. Perhaps the most hypermodern of all is Alekhine's Defense, in which Black responds to 1. e4 with ...Nf6!?, inviting white to push the same pawn again and attack the knight. Alexander Alekhine's theory was that black could entice white to overextend his pawn center, whereby it would become weak in the rear.

Today Alekhine is remembered not so much as a hypermodern player, but as a well-rounded champion like Capablanca, whom he defeated in 1927 for the World Championship. Fun fact: Capablanca is on record as saying, "At no time were there ever more than about 15 world-class masters, and 10 or 12 would have been nearer the truth." He was referring to the period of the late teens into the 1920s. Today things are much different.

The first five official grandmasters were nominated by Tsar Nicholas II at the 1914 St. Petersburg tournament: Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine, Siegbert Tarrasch, and Frank Marshall. There was no rating system in place until 1948 when Anton Hoesslinger came up with the Ingo System. Kenneth Harkness came up with a different system in 1956. Arpad Elo's system, now the most common, was first implemented by the USCF in 1960.

Soviet/Russian Hegemony

Chess became enduringly popular in Russia from about the time of Mikhail Chigorin, in the late 1800s, the first outstanding Russian Master, and chess remains as popular in Russia today as baseball is in America. By the 1920s, many of the world's top players hailed from the Soviet Union: Alekhine, Nimzovich, Bogolyubov, Mikhail Botvinnik, and many others.

Russian mastery of the game among the world's elite continues to this day in players like Ian Nepomniachtchi, Alexader Grischuk, and Sergey Karjakin.

Bobby Fischer, of the United States, was the only American player able to break down the Soviet chess wall during the Cold War, and once he reached his peak strength in about 1970, there was no one on Earth who could stop him. In 1971, on the road to the World Championship, he routed Mark Taimanov first, in a Candidates' Match of first to 6 wins. Fischer won the first 6 games without a loss or draw. Then a few months later, he did the same thing again to Bent Larsen, 6 wins, no losses or draws.

The World Champion was Boris Spassky, and the two met in a match in 1972 that captivated the entire world, even people who knew nothing about chess. Everyone on both sides wanted to see the political ramifications if Spassky won or if Fischer won. Fischer was extremely difficult to work with, losing the first game by a very strange, elementary blunder in a drawn endgame, then refusing to play the second game and forfeiting it over conditions in the playing hall.

Spassky began the match, thus, with 2 wins, a huge advantage. The match was the best of 24 games, and Fischer soundly won 12.5 to 8.5. His win with the black pieces in Game 13 is a victory for the ages.

Unfortunately for chess history, Fischer refused to defend his title three years later against Anatoly Karpov, imposing impossible demands that FIDE could not grant. Karpov was declared winner by forfeiture and the world will always wonder whether he could have defeated Fischer in a match. Karpov's successor, Garry Kasparov, has said that it would have been a very close match.

Karpov did not want to be thought of as undeserving of the title, and proceeded to win 9 very strong tournaments in a row. This record was broken by Kasparov, who still holds it with 14.

Kasparov, Computers, and Carlsen

Computers were not very strong compared to the world's best grandmasters, until about 1996. Kasparov, who defeated Karpov for the championship in 1985, would hold the belt for 15 years, the second longest reign after Lasker's 27. But chess theory had advanced greatly since Lasker's day and there were many more much stronger opponents in Kasparov's time. He consistently remained head and shoulders over all of them until dethroned by Vladimir Kramnik in 2000. Kasparov was not past his prime, just strangely out of form. He remained the highest rated player in the world until 2005, becoming the first person ever to breach 2800 Elo.

His defeat of Karpov in Game 16 of their 1985 Championship Match is, in this blogger's opinion, the greatest masterpiece in the history of the game. Kasparov's playing style remains possibly the most universal in history up to now: he could play sharp tactical chess but was primarily ultra-positional. He could do it all.

Game 16, Karpov vs. Kasparov. The black knight dominates White's entire center.

Game 16, Karpov vs. Kasparov. The black knight dominates White's entire center.

By the time of Karpov, chess theory had finally taken on all the complexities it still has today, meaning if Karpov in his prime, knowing what he knew of the game in 1980, were to be pitted against Magnus Carlsen today, it would probably not be a lopsided match.

Kasparov was the first major player to champion the inclusion of computers into preparation and study of the game, and he defeated the strongest computers of the late 1980s and early 1990s in several highly publicized matches. He was finally defeated by the supercomputer Deep Blue in 1997, the first time a computer had defeated a world champion. He has always mantained that human collusion was involved in helping the computer select the correct move at crucial moments. Deep Blue was dismantled afterward.

Today the strongest computers compete in their own world championships, and the current Computer World Champion is Komodo. If Komodo were to be equipped with an Intel quad core i7, 1.8 GHz, 16MB Hash, it would soundly defeat Magnus Carlsen in a match. In 2005, computers were finally seen as much more powerful than any human could ever become with the defeat of Michael Adams, 7th in the world at the time with a rating of 2737, by the supercomputer Hydra. Hydra won 5 of 6 games and drew one.

Humans, meanwhile, are also becoming stronger and stronger with the help of computers for analysis, research, and opening theory. We often hear of "novelties" in strong tournaments and matches. These are new moves in openings, and they are how the general theory of chess advances. Carlsen, current world champion at the time of this blog, is not resting on his laurels. He has won the last 4 tournaments in which he participated, and has not yet lost a game in 2019. So far this year, he has played 31 games under classical time controls and has won 17 of them against the world's best players, drawing the rest.

He holds the record for highest rating in history at 2882 in 2014, and currently holds an official rating of 2861 and a live rating of 2875.