Bobby Fischer Poem and William Lombardy

I have decided to start a series of blogs in the new year. As I thought about it, many ideas presented themselves. I may pursue them later, but as it is Christmas time, I thought I would start with a series of blogs honoring three people who have deeply and profoundly affected my attitude toward chess and life. The first blog, today’s blog, will set the background.

Toward the end of his life, William Lombardy visited the Mechanics Institute in San Francisco, California. I remember when he came in and sat next to me on the first day of the Imre Koenig event. This was a special two-day round-robin event where invited grandmasters competed against each other. If I remember correctly, there were only four players, Daniel Naroditsky and Sam Shankland.

I did not recognize the stranger who sat next to me, but John Donaldson, the MI chess director, did. He greeted him and brought out an old picture of a chess event with Lombardy sitting in the front row. Handing the picture to Lombardy, he asked Lombardy if he remembered. Lombardy smiled. Then John invited him to join us the following day for a special grandmaster luncheon.

After the luncheon, while I was cleaning up, Lombardy and I talked. I asked him what I could do to improve in chess. I told him I studied games by analyzing them, but It was a prolonged and time-consuming process. He suggested I spend 10 minutes daily going quickly through as many games as possible. “That won’t work,” I responded. So he tried a different track; he asked me if I stopped it every few minutes to analyze it when I listened to music. He had a point; I do not stop the music every few minutes while listening. Lombardy and I spent an hour or two that afternoon discussing many things. We had a wonderful time.

After that event, Lombardy often visited the MI, especially on Tuesday nights when the place was buzzing with people. Tuesday is the night of the historic Tuesday Night Marathon, which often draws more than 100 players.

As participants finish, they gather in the skittles room with walls covered with pictures of famous chess players. A tall picture of Tal smoking his cigar is on one side, a photograph of Spassky giving a simultaneous exhibition at the Mechanics Institute on the other side. Over the door to the office is a framed picture of Bobby Fischer on the cover of Time magazine. Additional pictures are scattered over the walls, such as Frank Sinatra and Walter Browne playing chess, giving the room the comfortable feeling of a home rather than a club. The room is filled with solid wooden chess tables, each with its history.

On Tuesday nights, the room is packed as the players of the Tuesday night marathon stream in. “What would you have done if I played this?’’ “Why did you play this move?” “What were you thinking here?” “You nearly got me there.” “Why didn’t you play this move?”

These questions, asked quietly at various tables as players analyze their games at each table, give the room a quiet buzz of fellowship and camaraderie. Lombardy and I were sitting at one of the tables across from each other. He had been talking to one of his friends, who just had left. So I sat across from him, handing him a poem I wrote about Bobby Fischer. I always wondered if my portrayal of Bobby Fischer was accurate, and here I had someone who knew him well. I was not going to let this opportunity slip by.

At first, he was reluctant to read it, but he agreed. As he started reading the poem, I heard him comment, “I like this….” “The wording here needs to be changed…” etc. When he had finished, I looked eagerly at him. “Did I capture Bobby Fischer?” He nodded; there was a pause, and then I heard him quietly say, “It could have been me.”

Bobby Fisher

Bobby was a person unique

he played chess when it wasn’t chic

he applied his mind to each square

with an intensity very rare

his world soon became a place well-defined

focus on line and row clear in his mind

logic and poetry he could see

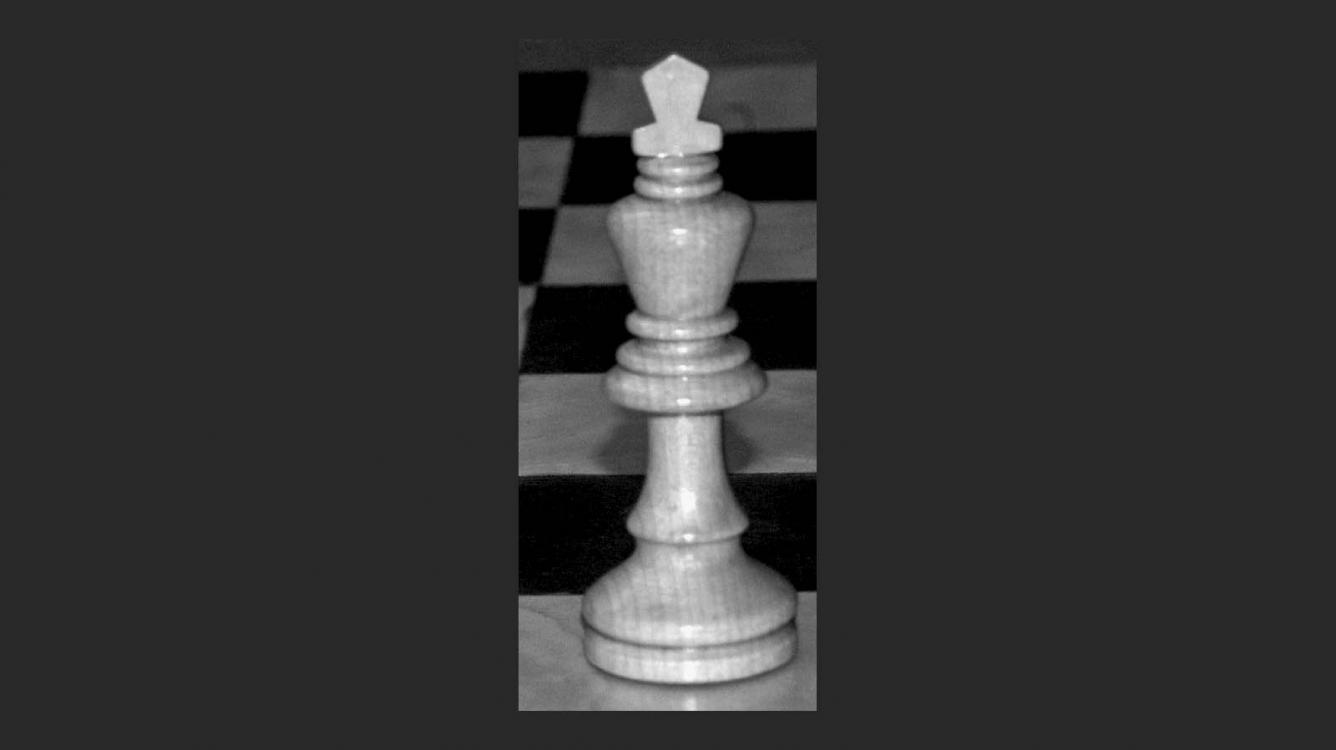

in wooden pieces of little value to you and me

To maximize the personality of each piece

each opportunity, he would seize

fiercely he defended the right to each square

for his pieces to be there

The pure world of black and white

Was his delight

The world of grey, he could not understand

How does one against a world of grey defend?

today black is black

Tomorrow black is white

how does one set such confusion aright?

How does one address with logic and art

A world whose internal consistency is torn apart.

-------------

You ask me if I, as a chess genius, do I myself see

if I say yes, you despise me

if I say no, that is ok

it’s what I am expected to say

so I should speak what is not true

to satisfy you

This is abhorrent to me

The logic of it I cannot see

I’ll return to a world where I am free

to speak about things

as they appear to me.

-----------

At the board, my thoughts are judged by checkmate, or I resign

be it his words or mine

A draw can be -- but on that, we both agree

the framework of decision-making is clear

There is no grey here

I prefer to put my energy

in a world of black and white

wrong and right

a world that seems to me

a little less confusing and wobbly

you see

when I played for world victory

you stole that world of chess from me

by questioning my integrity

you destroyed my inner harmony

@Renate-Irene