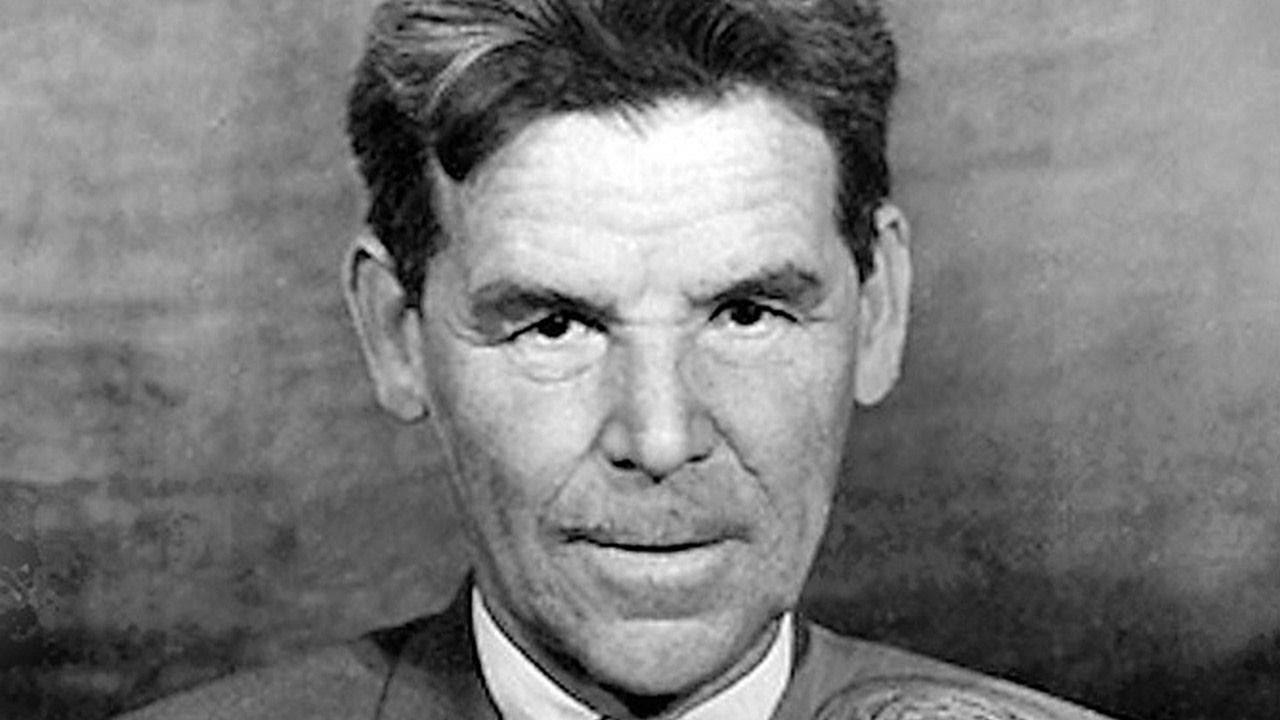

Why Rashid Nezhmetdinov Never Became a Grandmaster?

This is an excerpt from the book The Chess History of Tataria by Marat Khasanov, published at the Tatarstan Republic Chess Federation site.

http://www.tat-chess.ru/publ/pochemu_r_nezhmetdinov_ne_stal_grossmejsterom/1-1-0-14

As Nezhmetdinov's name became more well-known, people often asked if he was a grandmaster-strength player, and if he was, why didn't he become one? I often heard chess fans asking Rashid Gibyatovich himself about that. He would literally explode. "There were no tournaments!" he would scream. (Of course, he had a different version for the press.)

Let's check that. Nezhmetdinov could really become a grandmaster in 1954-1958, when he was on his performance peak. How many grandmaster tournaments were held in the USSR back then? Exactly one: Alekhine Memorial of 1956. Five grandmasters represented the Soviet Union: Botvinnik, Smyslov, Keres, Bronstein, and Taimanov. Masters weren't invited to such tournaments, so Nezhmetdinov never had a chance.

And now let's look which Soviet players did become grandmasters in that period:

1954 - nobody.

1955 - one player, Boris Spassky. He won the youth world chess championship and qualified for the Interzonal, where he got his grandmaster's norm. Boris was very lucky. The world championship in Antwerp ended on 8th August, and the Interzonal, which, luckily, was held in Gothenburg, began in a week - on 15th August. And Spassky got there in time, which, considering the Soviet bureaucracy of the time, was quite a feat.

1956 - again just one player, Viktor Korchnoi, by accumulated results.

1957 - only one player again, Mikhail Tal. He won the Soviet championship.

In 1958 and 1959, no Soviet players became grandmasters.

So, in six years, from 1954 to 1959, only three Soviet players became grandmasters: Spassky, Tal and Korchnoi. How was Nezhmetdinov supposed to become a grandmaster if he never played in a tournament with grandmaster norms?

Younger players might ask: OK, there were no tournaments in USSR, why couldn't he just play abroad? The answer is simple: the Soviet people lived behind the "iron curtain".

This term was popularized by Winston Churchill, who said in March 1946 in Fulton, "The iron curtain came down across the whole continent." Soviet citizens were forbidden to go abroad without express permission from the authorities. On 8th June 1935, a law was passed that punished escaping through the state border with execution, with the criminal's relatives getting punished too. In 1962, of course, nobody was executed anymore, but the Leningrad city court sentenced the defector Rudolf Nureyev to 7 years of imprisonment and confiscation of property "for treason". Any contacts with foreigners had to be approved by the authorities, or else you could've ended up in jail... Very few players could play abroad at the time.

Korchnoi remembers Nezhmetdinov: "I played my first tournament after my marriage in Sochi. This was the Russian SFSR championship, and it was won by Nezhmetdinov, one of the strongest Soviet masters. For some reason, he was very rarely allowed to go abroad, and, obviously, he never became a grandmaster because of that. [Nezhmetdinov was awarded with the IM title after finishing second in Bucharest 1954; it was probably the strongest foreign tournament he played in. - Sp.]

Was Nezhmetdinov a grandmaster-strength player? Let's look at his results in 1958 - the last year of his peak performances. We already know about the 1958 Russian SFSR championship from Korchnoi. Then he won first place at the first board in the Spartak sports society team championship. After that, he won the Soviet championship semi-final in Rostov-on-Don, scoring 10/15. And, finally, there's the mini-tournament of the Soviet team championship in Vilnius. Look into the tables and make your own conclusions.

18th Russian SFSR Championship, Sochi 1958

Soviet championship semi-final, Rostov-on-Don 1958

USSR Team Championship, Vilnius 1958 (1st board)

You might think that 4.5/8 isn't that great a score. But look at the line-up: Kholmov, Korchnoi, Geller, Keres, Bronstein, Boleslavsky; with exception of Shishov and Zilber, who finished last, everyone else were supergrandmasters! And Rashid Gibyatovich was on equal footing with all this chess elite. His results obviously show that at his career peak, in 1956-58, Nezhmetdinov reached grandmaster level. This is also proven mathematically: Chessmetrics, the site that calculated the Elo coefficients for the players before 1970, placed Nezhmetdinov in his best years as the 21st in the world, rated 2706. In the world, not just in the Soviet Union! GM Suetin wrote, "I'm sure that now, Nezhmetdinov would surely get his grandmaster norm, but he was born too early."

Belokopytov, in his book about Nezhmetdinov, also asked that question. He wrote, "Why such a brilliant player failed to reach the Olympus of the chess art, failed to become a grandmaster? I asked Nezhmetdinov himself about that, very delicately. Rashid Gibyatovich smoothed out his champion's band, thought for a long time, then said, "Many chess fans ask me that question. They can't understand why I didn't get the grandmaster's title. Frankly, there's nothing surprizing about that. Prominent players, such as Botvinnik, Smyslov, Tal, Spassky, Fischer, performed brilliantly already at the age 15, both in their countries and abroad. And I was only beginning to study chess at that age. All modern grandmasters had a solid theoretical base around age 20, becoming masters. There was a 20-year gap between them and me. And this, obviously, was the main obstacle that didn't allow me to become a grandmaster. It's only logical." The master's answer was very simple and clear."

Valentin Ivanovich wasn't a chess player, but he wrote a good, professional book, without lies. He worked in the Kazan Building and Engineering Survey Trust with my father. When he worked on the book, he researched diligently, even discussed chess with me. In addition to the book about Nezhmetdinov, he wrote such diverse books as The Kazan Streets Are Named After Them, Horrible Years: The History of the 1921-22 Famine in the Volga region, and The Priceless Riches (about oil workers). When I asked him why he suddenly started working on a chess book, he answered bluntly that he was summoned to the party's city committee and asked to write about Nezhmetdinov...

As we know, you don't argue with those who pay you. Of course, the text was checked rigorously and couldn't deviate from the party line. Nobody would've allowed to write that Nezhmetdinov didn't become a grandmaster because of a political barrier that stood between USSR and the foreign countries for decades.

Nezhmetdinov, member of the party's city committee and former commissar, was always fully loyal to the communistic regime. Even in smallest details. I remember that in 1972, when Spassky trailed Fischer 8-11 or so, a cultured-looking man approached Rashid Gibyatovich in the club and started to ask his opinion on how this match would end. He was very insistent. Nezhmetdinov ignored the man for a long time, but then his face suddenly lit up, and he said calmly, "I believe that Boris Vasilyevich will pull himself together and defeat the American." The man nodded silently and left. Rashid Gibyatovich went nuclear after that. "Who is this provocateur?" he asked us. Nobody of us knew him. After some select curse words, Nezhmetdinov approached the club director, Semyon Platonovich, and told him, "Never let this provocateur in here again!" And indeed, I've never seen that man in the club again.

Still, Nezhmetdinov did get a chance to become a grandmaster. During the Khrushchev's thaw, Soviet players started getting more opportunities to play in international tournaments. And so, when Nezhmetdinov was almost 52 years old, he was finally invited to a tournament in Sochi with a grandmaster norm. In those times, you only had to get a single grandmaster norm to become a grandmaster. The age already took its toll, and Rashid Gibyatovich was past his peak, but he still fought on.

Here's the short story of the tournament. In the first round, he got White against Ujtelky. This player is known by his variant shown on the diagram. Regardless of White's play, Black arrange their pieces like this:

Then, depending on the situation, Black can castle to either side, attack the center with pawns, or just sit there and do nothing. On the high level, Spassky once used this system against Petrosian and managed to draw.

Nezhmetdinov got positional advantage out of the opening, then won an exchange for a pawn. The computer evaluated the position at +2.70, or, in other words, it was won. But in time trouble, Nezhmetdinov suddenly lost a second pawn, worsening his position considerably, The game was adjourned in a roughly equal position. During the play-off, White didn't want to put up with the inevitable draw, sacrificed (incorrectly) a Knight, then a Bishop, and lost.

After four rounds, Nezhmetdinov had 2 points and played White against Boris Spassky, already a world championship candidate at that point. Spassky sacrificed an exchange and got some compensation, but after the adjournment, Nezhmetdinov gave the exchange back and created an unstoppable mating attack. Some games were good, some were really bad, and in one of the last rounds, Nezhmetdinov played against Antoshin. This was the decisive game. I'm putting it here without much chess commentary.

Nezhmetdinov analyzed this game many times, for long. Now, you just can turn on your computer, and it will show all main lines to you. But back then, you could've searched for years, and still the best moves would elude you. I think I first saw Nezhmetdinov analyzing this game in 1969. He didn't work on it alone: he was assisted by Voloshin, Smirnov, Gazizov, Konyukhov - all the strongest Kazan players, except Engels Valeev. He wasn't on speaking terms with Nezhmetdinov. For me, a third-category player, the position was too difficult, and I've only stood and watched silently. Rashid Gibyatovich would usually listen to Yura Smirnov, mostly ignoring Voloshin's moves. The computer thinks that this position is equal. But it's obvious that the position is very difficult for both sides. I didn't know what a game it was back then, but I saw how agitated Rashid became and how important it was for him to find that win. We have extensively analyzed the variants starting with 21. Bf4, and after Qd8 (21... e5 22. Re1), we looked at the Knight sacrifice, 22. Ng6!! fxg6. After that, we would look at 23. Re1 and 23. Nxe6. Now, with the advent of computers, the culture of collective analysis is almost lost. In earlier times, three masters could make the moves and commentate what's happening at the same time, not interfering with each other and understanding each other immediately. I would look at all those hands over the board, and I was glad that this position was too difficult even for masters, not just me... Sometimes, we would checkmate the Black during the collective analysis, sometimes, we wouldn't. Anyway, in the game, Nezhmetdinov decided just to open the lines for attack.

When chess players asked Nezhmetdinov why he never became a grandmaster, he would ruefully sigh and show him this position. I saw him showing this position in 1970, 1971, 1972 and even 1973. He played 31. Bb7. He could get good winning chances after 31. Ba8! The difference is simple: after 31. Ba8, there's no 31... Kc7 due to 32. Qc6+ Kb8 33. Qb7#. Another idea for 31. Ba8 is to win a tempo after 31... Rc8 32. Bb7. The Black Rook is under attack, and it compromises their defence. After 32... Rc7 33. d4, the game opens up, and White have a crushing attack. And after 31... Rxa8 32. Qxa8 Nxg3! 33. Nxh8 Ne2+ 34. Rxe2 Qxe2 35. Qxf8+ Kc6 36. Qe8+, White have an extra piece and should convert it in the endgame, though it won't be quick. During the analysis, Nezhmetdinov managed to convince everybody, including himself, that he had a win. He did have grounds for that: it's hard to defend a position with a centralized King in time trouble.

Of course, he saw 31. Ba8, and showed everyone the winning variants. In my first years, I would look silently, but later, when I became the Tatar ASSR schoolboys champion, I got a voice too, so I said, "This looks like Turton doubling." Nezhmetdinov was stunned: "Haven't heard of that, what it is?" I showed him an old problem.

Solution: 1. Bh8! The White Bishop paves the way for the Queen: 1... b4 (White threatened with 2. Qa3# or 2. Qc3) 2. Qg7! The pieces are doubled and ready for action! 2... Ra8 (White threatened 3. Qa7#) 3. Qb2#. This maneuver became known as Turton doubling.

Our coach Emil Elpidinsky liked to show us this problem. Now I understand why. When he showed us positions from actual games, he would often have to answer the questions of curious pupils who played much stronger than him: "What if we make this move, or that move?" He didn't know how to answer, and he couldn't predict what the young players might ask. Turton doubling was perfect for his storytelling and improvising talent. Three variants completely exhaust the position, there are no unexpected questions. So, Turton doubling became the peak of his coaching skill. I saw Emil show this position around five times, and he would always begin talking about Turton, and then freely improvise about the beauty of chess, music or art, or about the modern youth being lazy and uncurious - this depended on his mood. Emil Vasilyevich might never tell you a word about Queen's gambit or the Ruy Lopez, but every single pupil of his knows the Turton doubling! I knew almost nothing, except for this maneuver, but still, I've managed to surprize the old master. Rashid Gibyatovich said nothing that day, but three days later, on Sunday, when there were many people in the club, he would show the Antoshin game to the amateurs, and, commenting on the unmade move 31. Ba8, suddenly said, "This looks like Turton doubling!", raised his index finger, added, "You have to know that", and looked at me. The fans said, "Wow, he didn't become the Distinguished Coach of the Soviet Union for nothing!" I was astonished, to put it mildly.

Getting back to the game, I have to say that 31. Bb7 wasn't the losing move yet, but victory slipped through Nezhmetdinov's fingers, and draw wasn't too different from a loss for him from the table's point of view.

Rashid Gibyatovich was a very impulsive man, and losses upset him quite heavily. Probably due to that, in the next round Nezhmetdinov agreed to a draw in a better position after just 23 moves, and he couldn't make the grandmaster norm by 1.5 points. He scored 8.5 points out of needed 10. The fact that six years past his peak, aged 52, Nezhmetdinov still managed to score 85% of a grandmaster's norm, only proves that during his most stellar performances, Rashid Gibyatovich was a grandmaster-strength player, but simply never had a chance to achieve that elusive norm! And after he turned 46, it was already hard for him to withstand the intensity of tournaments. Your memory can't register the novelties all that well, your calculation skills get numbed. It's pure physiology. Nezhmetdinov was sure that if he won that game against Antoshin, he would've gotten his norm. He would emotionally share his sorrow with many people, managing to convince most of them. Obviously, if he won that game, he wouldn't have made that quick draw next day... So, Rashid Gibyatovich was pretty sure that a single chess board square decided everything for him. He was very upset. He thought that if he moved his Bishop just one square further, he would've become a grandmaster. A ridiculous accident! Though, to say the truth, there's nothing accidental. In my humble opinion, Nezhmetdinov didn't like 31. Ba8 because after that, he would've had to convert his material advantage in a long and boring endgame, but he wanted to checkmate his opponent - his desire to attack compromised his technique... Why do I think that? I know his chess tastes. Here's an example. He once showed us a beautiful combination, but there was a hole in it. Everyone analyzed various moves and were glad that they managed to find a refutation. Nezhmetdinov came to us, pushed the pieces off the board, and said, "You've defiled such a beauty." He was so upset that he stopped the lesson after that and told us to go home. And there's another example. He started one of the lessons by saying, "I can't understand why aren't they giving titles for beautiful playing. I'm going to show you a game played by a first-category player. I would've awarded him with the master's title on the spot." Chess beauty was more precious to him than chess truth. That's why he remained "a grandmaster of the beauty" and didn't become a chess grandmaster. But sport is sport, and chess is sport!

Chigorin Memorial, Sochi 1964