Winner's POV Chapter 2: London 1851

In Winner's POV, we take a look at tournaments from the 19th century and see the games that allowed the top player to prevail. Some tournaments will be known and famous, others will be more obscure - in a time period where competition is scarce, I believe there is some value in digging for hidden gems in the form of smaller, less known events.

Chapter 2: London 1851

In the last chapter, we looked at the first tournament with complete documentation (to the best of my knowledge); now, we jump three years into the future to discuss the first international tournament, one in which chess masters from across Europe were free to enter.

While trivial today, transportation was one of the main issues that prevented international tournaments from being held for quite some time. Travelling was a rather arduous process - especially given that England is disconnected from the rest of Europe - so for the majority of the game's history, masters were forced to play one-on-one matches to determine relative skill. However, the Crystal Palace Exhibition provided a convenient way to gather. Passports, time off work, and other factors limiting travel were greatly alleviated by this grand event. For the first time in history, masters across the continent were able to congregate and test their mettle.

Howard Staunton, unofficially regarded as the world's strongest player, personally undertook many of the duties in organizing the tournament. In his tournament book, The Chess Tournament, he goes to great lengths to explain the many trials and tribulations that came with such an endeavor. Since we're not here for that today, let's move on to the tournament itself.

Format and Prizes

This is another knockout tournament, as are the next five I have planned for the following chapters (I think). The original plan was for this to be a 32-man tournament, and as Staunton explained, this is why the original plan was a first-to-two-wins system like the Ries' Divan tournament. However, after the first round, it was decided that the required number of wins would be increased to four. There was also a loser's bracket of sorts, as there were eight total prizes to hand out, however we only care about the first prize.

While the prize fund is discussed in the tournament prospectus, a look at the accounting section of the book provides a much simpler picture:

£183 in 1851 is apparently worth £12,346.25 in 2022, which is a much more lucrative prize fund than before. Each player was required to give a £5 deposit for entry, so everyone who won a prize would win their money back at least; not too shabby.

Players

Staunton lists the players in his tournament book, though the format is much less neat than the last one:

To make matters worse, this part of the book was split across two pages, hence the two screenshots. For a potentially more readable list:

From Hungary: Jozsef Szén, Johann Löwenthal

From France: Lionel Kieseritsky

From Germany: Adolf Anderssen, Karl Mayet, Bernhard Horwitz, Edward Löwe (though the latter two had been living in England for quite some time)

From England: Howard Staunton, Marmaduke Wyvill, Samuel Newham, Hugh Alexander Kennedy, Elijah Williams, Henry Bird, James Mucklow, Alfred Brodie, Edward Shirley Kennedy

Of course England would still provide the majority of the field, but for all intents and purposes, this was an international tournament.

Referring to Edochess again, the strongest players from 1851 present were Anderssen (3rd, behind Paul Morphy and Tassilo von Hydebrand und der Lasa), Staunton (5th), Kieseritsky (7th), Szén (9th), Williams (11th) and Löwenthal (12th).

It may be more accurate to use the 1850 rankings as the 1851 ranks probably used this tournament, in which case it would still be the above players; the ranks however would be Anderssen (3rd), Staunton (5th), Kieseritsky (6th), Szén (11th), Löwenthal (12th), Williams (14th). Irrespective of which year you'd like to use, it's impossible to deny that this was a star-studded event.

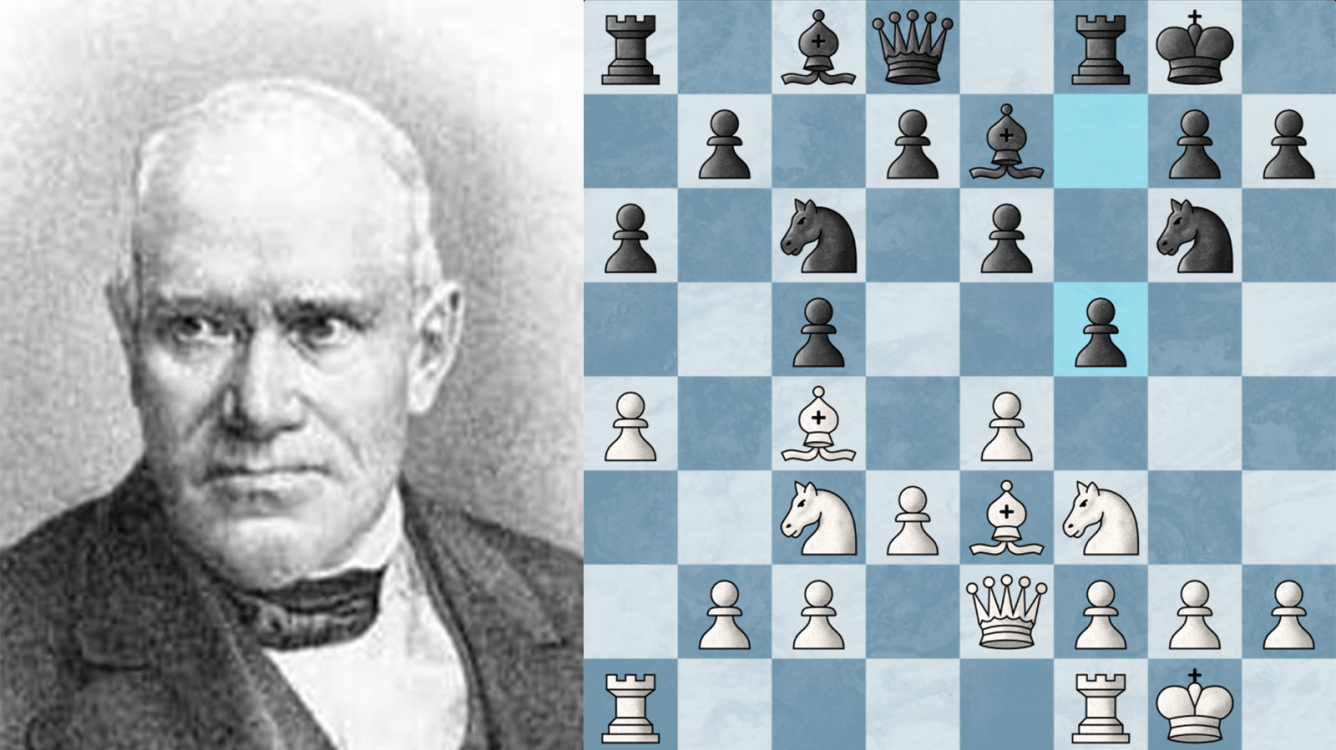

The Winner: Adolf Anderssen

Adolf Anderssen picked up his first-ever tournament victory here at London 1851, and if you know anything about Anderssen, you know that he did not stop here. In fact, he won a second tournament in 1851, but I doubt I'll talk about it; you can read about it here. Without further adieu, it's time to look at the London 1851 tournament from the Winner's POV.

Round 1: vs. Lionel Adalbert Bagration Felix Kieseritsky

I had to write his full name at least once, and probably only once.

France was the dominant chess power for easily half a century, with memorable figures like André Danican Philidor, Alexandre Deschapelles, and Louis-Charles Mahé de La Bourdonnais each being considered the world's strongest player during their era. Since Staunton unofficially held that mantle during this time, you know Kieseritsky was more than eager to gun for it himself. Of course, to get there, he first had to get through Anderssen.

Anderssen unveiled his opening weapon of choice for this tournament, the Sicilian, to which Kieseritsky responded with 2. b3. The opening was strange, as were many openings during the romantic era, but technically playable. Kieseritsky tried to set up some play on the Kingside, but after Anderssen defended, the Frenchman found his Queen in a little danger. What followed was, according to Staunton's notes, one of the worst blunders he had ever seen in a game, irrespective of the level of the players or the stakes of the game.

Feeling no fear whatsoever, Anderssen went all-in on the King's Gambit for the second game, choosing a particular line in which Kieseritsky had some experience. This experience helped, as he was able to fend off Anderssen's attacks, and even forced the German to play accurately in order to not be worse. Eventually, Anderssen was forced to accept liquidation that left him a pawn down in a Rook endgame.

The endgame itself was not played too well, as endgame theory was a little spotty back then. Kieseritsky had a couple of chances to win, Anderssen had a couple of chances to draw. The players did eventually call the battle a draw, but one would think that Kieseritsky would have levelled the score on a good day.

The players then played a similar line as the first game, once again getting a playable position from this strange Sicilian sideline. It didn't take much for Kieseritsky's calculation skills to falter, and he very quickly dropped a piece, falling victim to Anderssen's lethal Bishop pair. A very strong (and possibly unexpected) start for Anderssen, and a very early exit for the Frenchman. Staunton later notes that he used this game as one of the driving factors behind increasing each match to first-to-four-wins.

Round 2: vs. Jozsef Szén

Szén was the strongest player from Hungary, and had obtained a reputation from travelling Europe and playing many strong masters in the 1830s, including La Bourdonnais. The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 had brought about a ban on all club activities, including chess, so for some time, Szén was grossly out of practice. He easily swept aside the Englishman Samuel Newham 2-0 in their first round match, however, so he was certainly not going to be an easy opponent.

The French defense was one that worked well to nullify any aggression Anderssen may have wanted to vent, forcing the German to play slow. Szén was an excellent endgame player, and was known to win many games by chopping off pieces and outplaying his opponent in the endgame - something Anderssen had to be careful to deal with. Things took an interesting turn, however, when Szén allowed his opponent a strong passed d-pawn in exchange for pressure against Anderssen's King.

The twists and turns continued, as apparently a spectator shouted the "winning" move for Szén before he was able to play it (it wasn't necessarily winning, but it was the objective of Szén's plans). The Hungarian played a different move, and shortly after his attack was refuted, lost the game. A gentlemanly thing to do, if nothing else.

Szén's weapon against Anderssen's Sicilian bears his name, the Szén variation. It was an extremely messy and complicated affair, with Szén's Queen grabbing a pawn on b7 and Anderssen failing to correctly punish such aggression. The White Queen would end up being the MVP of the game; after the chaos was liquidated off the board, it soon ate two more of Anderssen's pawns, stole Black's castling rights, and forced resignation relatively quickly. An amazing game to bounce back from the first game's debacle.

Anderssen experimented with 1. d4 in game three, and I think it's unsurprising that he would rarely play the move again afterwards. You always have to keep your eye out for tactics, even in supposedly quiet positions, and Szén was definitely the better of the two players in that department.

An interesting development came out of the third game, according to Staunton. It was no secret that these two were good friends, as they shared a room in their hotel while they were in London. However, apparently the two made a deal that, if either were to win the tournament outright, they would give the other one-third of their winnings. I've yet to find any proof of this besides Staunton just writing it in the tournament book, where he also claimed that the deal altered the players' play for the rest of the match. Let us be the judges of that, eh?

In a closed Sicilian, Anderssen showed off why he was one of the best opening players in the world, quickly equalizing and even having the advantage over Szén after the Hungarian had to undevelop his Knight to dodge a fork. Though Anderssen missed the most precise wins possible, he held the advantage the entire way, eventually ripping open Szén's King with a brutal attack.

Szén tried to copy Anderssen's system from game 4, but quickly ran into issues when Anderssen refused to open the f-file for him. Once his Knight got stuck on a5, Szén had to make concessions on the Queenside which Anderssen eventually used to great effect. The Hungarian's Kingside expedition was fruitless, and after a nifty pawn sacrifice, Anderssen was the one doing the Kingside attacking. A brutal game from Anderssen, who was basically winning all over the board.

Game 6 was probably the most lopsided of all. Szén quickly pushed all of his Kingside pawns, allowing Anderssen control of the center and command of the h1-a8 diagonal. Once Anderssen played the d4 pawn break, Szén's weak King was no match for Anderssen's incredibly accurate tactics, and the match was decided. Even if Staunton was correct, and the deal these two made influenced the last three games of this match, it's not like the path to the title was getting any easier.

Round 3: vs. Howard Staunton

The legend himself, Howard Staunton, would be Anderssen's semifinal opponent. Unofficial world champion, chief tournament organizer, and main game annotator for the tournament book, Staunton's resume was long and his plate was full of responsibilities. That did not stop him from having a nice tournament, however; he defeated fellow Englishman Alfred Brodie 2-0 in the first round, then dispatched the German Bernhard Horwitz +4-2=1 in round two. Staunton had a heart condition that made long games impossible for him (which is where both of Horwitz's wins came from, in 80+ move marathons), but that would hardly be an issue against Anderssen.

Staunton was widely considered one of the experts in the Sicilian, and while his 4... Bc5 innovation is pretty good, the exact way he played it left something to be desired. Anderssen's Kingside attack was expected, yet strong, and while Staunton was granted a chance to stop it, he failed to find the most accurate refutation. Certainly not the best game from Staunton, who tried to write it off as a mutually bad game.

For the first time in the event, Anderssen didn't play the Sicilian, opting for 1... e5 and allowing an Italian game. Staunton's intentions were clear early, as he doubled the pawns in front of Anderssen's King and began shifting pieces to the right. Anderssen, in turn, provoked 17. Nf5+ which further propelled Staunton's attack in exchange for an iron grip on the center. Anderssen was, once again, without fear.

What followed was a long, tense battle, with Staunton pushing all of his Kingside pawns, though with much better prospects than Szén. Anderssen's constant threats of breaking through the center made things difficult, and it was honestly very difficult to predict the outcome. Staunton noted multiple places where he missed a winning move, and eventually, he failed to recognize how strong Anderssen's Queen was in the center. A heartbreaking game for the British champion, and a fifth consecutive win for Anderssen.

Not satisfied at all with his performance last game, Staunton did everything in his power to repeat the setup this game and prove he was winning. He once again doubled the pawns on Anderssen's Kingside, but this time, he allowed Anderssen to gain the open h-file for his own attacks. Anderssen very well could have used this file for an easy win, but he made a tactical slip and gave Staunton a chance on move 21.

It made no difference on the final result, however. Staunton first miscalculated or misevaluated the endgame that gave him two Rooks in exchange for Anderssen's Bishop and Queen (with enough extra pawns for Staunton to keep the material equal), as his Rooks never coordinated and Anderssen promptly won one, giving him his sixth consecutive win. What a streak.

A winless Staunton again played the Italian, opting for the 5. d4 line this time around. You could tell he was getting more and more dejected, as he criticized 14. Qxc6 for being too reckless despite it being an alright pawn grab. As Anderssen built pressure on the Kingside, even assembling Alekhine's Gun, Staunton got nervous and let his advantage slip. Anderssen had the match in his hands, a 4-0 sweep practically locked in... then he made a blunder that was arguably worse than Kieseritsky's.

At this point, it was very clear that the tense match and match situation had been wearing on the players, as the sixth game was awful. Staunton's opening was awful, he was losing from the very start, but Anderssen wasn't able to put the game away nearly as quickly as he could've. I didn't manage to come up with good notes for the game, as there was no way to properly cover every aspect without the analysis being uncharacteristically long. Needless to say, Anderssen dethroned the unofficial world champion, and had firmly punched his ticket to the final round.

Round 4: vs. Marmaduke Wyvill

As a consequence of there being no seeding system - the players drew lots before each round to determine opponents - the final bout was between Anderssen and English Member of Parliament Marmaduke Wyvill.

For a quick recap of Wyvill's tournament: he defeated Edward Löwe 2-0 in round one, Hugh Alexander Kennedy +4-3=1 in round two, and Elijah Williams +4-3 in round three. If you recall the names I listed at the start of the chapter, you'll conclude that Anderssen's path to the finals was much harder, and he got there with much larger of a cushion in most matches. Still, all that mattered was what happened over the board, so let us see exactly what transpired.

Wyvill repeated Staunton's idea in the Sicilian of playing weirdly in the opening, though Wyvill's position was outright losing as a result. There's honestly very little I can say about this game; Anderssen simply blew his opponent off the board.

The second game was a lot more interesting, thankfully. Wyvill gave Anderssen his first exposure to the English opening, and the players went into a sensible Queen's Gambit Declined. Though both players missed things, it was Wyvill who more accurately capitalized on one of Anderssen's mistakes, winning a pawn and simplifying to a position where he could never lose. Similarly to Kieseritsky, Wyvill needed more than one pawn if he was going to win this game, which didn't happen. Unlike Kieseritsky, however, I don't believe Wyvill ever had serious winning chances once the Rooks were all that remained.

A main line Sicilian was on the docket for game three, and that would turn out to be Anderssen's biggest mistake. He was unable to ever break through on the Kingside, and the second he stopped applying pressure, Wyvill struck in the center. Anderssen was not sufficiently aware of the danger his King was in, and it cost him severely. An impressive tactical win for Wyvill, and with that, we suddenly had a real match for the title!

The preceding two games probably taught Anderssen something important: he would have much more success against Wyvill if he didn't play well-established openings. That theory would be well supported in this game, as Wyvill played a very strange series of ideas in an Anglo-Dutch. Anderssen once again broke through the center and went after Wyvill's King, finishing the game with a pretty Rook sacrifice that forced checkmate.

The next game was also a slaughter. Wyvill quickly rerouted his Knights to the Kingside, where they were of little help. Wyvill missed 14. Nxh7, after which Anderssen simply took one of the Knights and enjoyed the extra piece and the attack. Though Wyvill had played some good games, it was hard to think of this as the finals of the first ever international tournament, and not some club player Anderssen was playing in a simul while visiting.

Wyvill took a new approach for the sixth game, electing to copy Anderssen's moves for a while to ensure his opening wasn't too terrible. It worked, for the most part, and Wyvill enjoyed his first playable game since game three. It took until move 24 for Wyvill to finally commit a massive error, and although Anderssen let him off the hook, it still shouldn't have been much of a game after that.

Wyvill's tenacity, however, was not to be overlooked. In round two, he was losing 2-3 before winning two consecutive games to move on; in round three, the veteran Elijah Williams was leading 3-0 before Wyvill won four straight games to make the finals. He knew how to play when his back was against the wall, and when Anderssen gave him even a little hope (35... g6), Wyvill boldly sacrificed the exchange to fight for the win.

Honestly, this game is one of my favourites from the entire tournament. I highly suggest you give this game a look over, with more than just the notes I wrote for it. It's a treat.

Unfortunately for Wyvill, history was not going to repeat itself. He allowed Anderssen's Bishop to pierce right into his camp, and after Anderssen found a brutal exchange sacrifice of his own, Wyvill's tournament was over. A valiant effort, no doubt about it, but Anderssen's play was simply on another level.

Conclusion

The London 1851 tournament was a longer, stronger competition than its predecessor, and I hope that was accurately reflected in this post. Following this, Anderssen would be widely recognized as the strongest player in the world, or at least in Europe - though very few people knew about him, one boy from America would quickly make his mark on the chess world in a few years... but that's a story for another day.

After Anderssen notched his first tournament victory into his belt, he would stay in London for quite some time. The Immortal Game would be played here, and as previously mentioned Anderssen won another tournament that I don't believe is worth a full post. One of the rules in the tournament prospectus was, given the random nature of the pairings and the chance for the best players to not meet in the finals (as was demonstrated), the winner must hold themselves open to a challenge from any of the other competitors for a longer, proper match. Staunton himself issued the challenge, though scheduling issues and Staunton's heart complications prevented this match from ever properly occurring. And with that, we close Anderssen's chapter in 1851, and move on to something else... or do we?

Stay tuned for Chapter 3, which will be much shorter than this. Cheers!