The 64 - Chess & Cinema #1 - The Luzhin Defence

As Pushkin's doomed duelist said "Let's start, if you are willing." These lines are declared by an over swaggering Aleksandr Ivanovich Luzhin, who marches into the grand hall late (because all the best players make their opponent wait) proclaiming "there's a big victory coming! A big, big victory!", before tossing his cane away and blowing cigarette smoke into his rival's face as some sort of an intimidation tactic. At first, much like Jules' memorized bible passage from Pulp Fiction, quoting Pushkin before a chess match seems like some "cold blooded s*** to say to a m**** f**** before you pop a cap in their a**, and it is totally that (I plan on adding it to my oratory repertoire before starting... well, anything really), but perhaps also Luzhin "hasn't given much thought to what it meant."

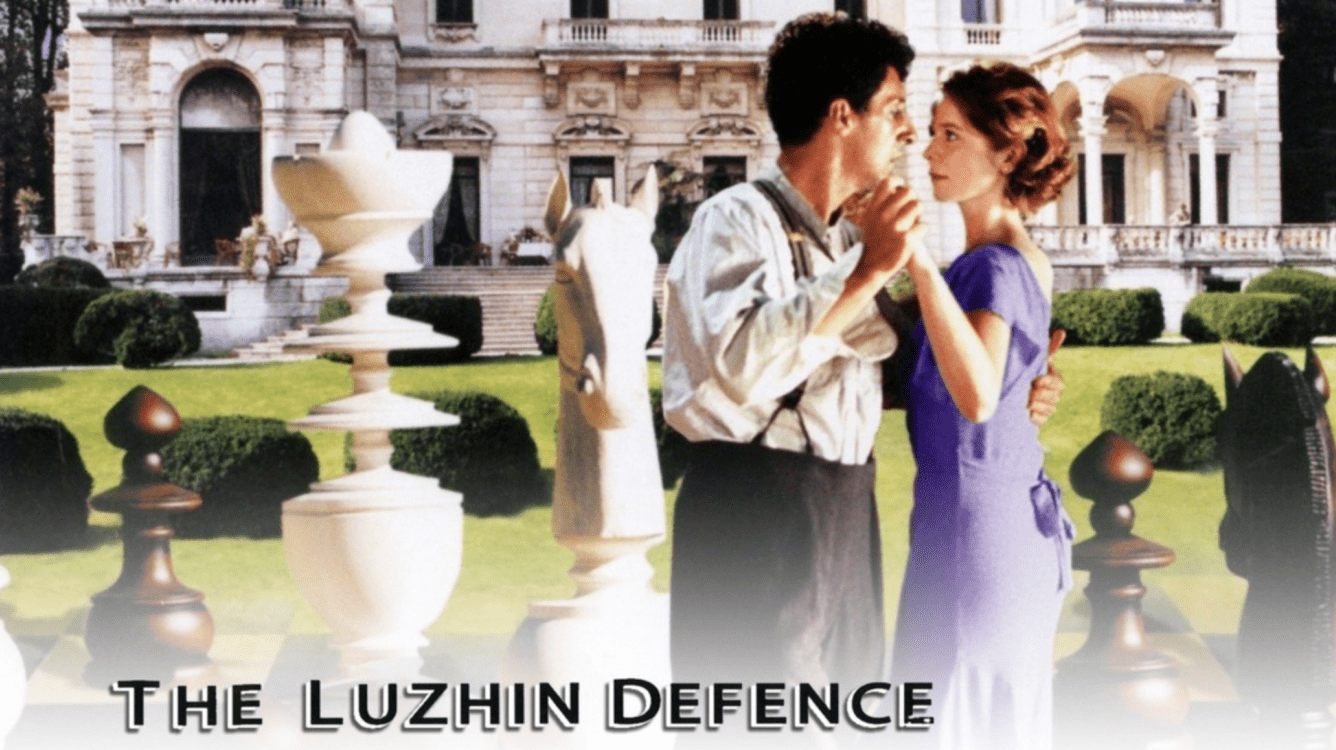

Chess & Cinema is a new blog where I review and analyze films about chess. The 2000 drama, The Luzhin Defence, is the first edition of what will be an ongoing series and is a complete spoiler filled review.

SPOILER ALERT! SPOILER ALERT! SPOILER ALERT!

There are many parallels to draw between one of Russia's most renowned literary figures, considered to be both Russia's Byron and Shakespeare, and the great chess mind who is Aleksandr Luzhin. The two were born of noble families, are desperately romantic, a virtuoso in their respected field of creativity, but most importantly, they both fancy a duel. Luzhin picks his battles on the sixty-four squares, whereas Pushkin chose the 19th century custom of using pistols and counting twenty paces. Regardless of the case, these contested skirmishes would consume both men, eventually becoming the leading cause of their ultimate demise.

The Luzhin Defence, based on the Vladimir Nabokov novella of the same name (or is the closest interpretation of the title as his third book has also been referred to simply as The Defence) is a story about genius and how it can drive one to madness, but it's really a love story, and I render a guess that depending on how much one swoons and pines over the romance of the film will tell the tale of how much the spectator buys into this not so faithful adaptation. The picture was released in the US during the Spring of 2001, starring a younger John Turturro as the titular absent-minded Luzhin, who lacks the aptitude for any small talk. The brash and bravado of the scene I previously described is far from the Luzhin we were accustomed to seeing but instead is the kind of guy who will only make eye contact with you if you are dressed like a shoelace. In regards to Turturro though, if he was twenty years younger again, the Italian-American thespian could dust off his chess set and take on the role of Fabiano Caruano when his biopic inevitably gets made. There's a striking resemblance and he would make a convincing doppelgänger.

The setting is a most romantic one, taking place in 1930's Italy, where all the top grandmasters are convening for a world-class chess tournament. On the boat ride over to the grand estate (the villa is actually the real life home of famed Italian film director Luchino Visconti), we meet the wealthy debutant Natalia, played by Emily Watson (Chernobyl), who can act with an eyebrow, vacationing with her disapproving mother, who in turn is trying to find her a capable suitor. Ironically enough, 'Natalya' was also the name of Pushkin's wife and although the truth of the events leading up to his fatal duel are shrouded in layers of obfuscation, the gossip mill persistently claimed that Natalya was unfaithful and the the face-off was fashioned around Pushkin's jealousy because she was having an affair with the handsome Frenchman who would end up firing that fatal shot.

The mother (Geraldine James), does not think the recluse Luzhin checks any of the suitable boxes to take her daughter's hand in marriage. That role is carved out for Count Jean Stassard (Christopher Thompson) who's main function of the story is not as a romantic foil but merely as an expository device for the audience who can't follow what is going on during the chess portions of the story.

But with all this talk about Pushkin and a novel that was originally written in Russian by Nabokov (who also wrote Lolita, which was adapted for the screen by Stanley Kubrick, another chess aficionado who is responsible for film history's most iconic chess scene ever. I'm obviously referring to the epic science fiction film, 1968's 2001: A Space Odyssey), the film is surprisingly opaque and most conventional when affixing a national identity to the central characters, most of whom are Russian in the novel. Instead, mostly everybody speaks in a high-mannered British accent, a ridiculous trope that has seemed to be played out across all film and television. I suppose it is somewhat apt, considering the book was relatively light on any sort of character development other than the protagonist. Natalia for instance doesn't even get a name in the novel but instead is only referred to as Luzhin's wife but the idea that if any character just speaks with an English inflection it's a clear substitute for any European or Asian nationality is rather laughable.

Marleen Gorris's film, who's previous work reproduced another adaptation by a highly venerated author, Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf, depends heavily on a flashback structure to unravel the younger Luzhin's tortured past. When just a young boy, he receives a glass chess set from his Aunt, whom his father is secretly having an affair with, causing Luzhin's mother endless agony to the point of committing suicide.

Even more so than his mother dying, being given this chess set is the inciting incident for Luzhin's entire life. He becomes entranced with the diversion, so much so that he knows the exact moment, to the minute, of when he started playing the immortal game (Nine thousand two-hundred and sixty-three days, four hours and five minutes, he says checking his small timepiece). Like most chess stories, Luzhin begins by playing his father but Aleksandr isn't the natural prodigy at first, even falling behind in his schoolwork, but eventually, he would go on to humiliate his father over the board to the point that their mutual attachment from there on can never be reprimanded, smashing his father's fragile ego. The child buries the delicate chess set but holds onto one piece, the White king, a sculpture he'll carry along in his coat pocket for years to come. This will be the first instance, and not the last, in which chess will fracture a human relationship Luzhin once had.

Then again, that is the thing with these fathers in these chess movies. They stink at chess and don't make as the best pedagog. Therefor, the mendacious and duplicitous Valentinov (Stuart Wilson), an antagonist who is only missing a wider mustache to twirl, offers to take the young boy under his wing, touring him around Europe as his own circus attraction having him play blindfolded, in simuls, as well as blindfolded simuls, all in the guise of 'nurturing' this young talent. The only narrative intrigue comes much later in the film when Valentinov resurfaces in the later timeline, with the only intent to make the older Luzhin succumb to defeat at the Grandmaster tournament. Just the very sight of Luzhin's old chess mentor and he instantly reverts back to being a child, insecure and looking down on himself. It is here where we begin to see his mental state starting to deteriorate.

Valentinov rattles his nerves, but why? Why does he try sabotage his former pupil at every step of the way? Well, he seems to be jealous over Aleksandr's God given natural chess ability, playing the role of Salieri to Luzhin's Amadeus but nothing shown on screen really warrants the lengths this cardboard cutout villain goes to assure his goal. The narrative as a whole lacks any real impending conflict. There are differences between Natalia and her oppressive mother, and some tension between Luzhin and his main competitor, Turati, a foe I've yet to mention because his only character function is to move the pieces opposite of Luzhin. Instead, the film enunciates its Merchant-Ivory period trappings, rather focusing on things that are left unsaid. The relationship between Natalia and 'Sasha', as she refers to him (a common Russian moniker for those with the name Alexander) is the best thing about the movie but there's hardly any background for the audience to understand what these two see in each other. As observers, we are simply told that they are in love, instead of seeing how they fell in love in the first place.

The Chess

One of the most difficult things to do with a chess movie is to make the chess look visually engaging. Gorris actually achieves this in a rather interesting way. The chess is at times impressionistic, reflecting Luzhin's inner turmoil (the one slight carryover from the book which explore the character's sickly state of mind.) Montage is used, showing the passing of time and accelerating the state of play. The way the pieces move and the banging of the clock captures a rhythm. The games, results and tournament/story as a whole fly across the screen in a rapid spell, abiding by the old cinematic term, 'cutting to the chase'. The scary nature of time trouble is amplified by the use of canted dutch angles, depicting madness and disorientation the same way the old German Expressionist filmmakers of the then silent era did.

Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

Sometimes Google is funny.

Soft focus is implemented while Luzhin sees the ghosts of dead family members while trying to concentrate, implying that it's not just his opponent he's battling when he plays but also his own personal demons. Lastly, there's also a clever use of jump cuts which is a great way to photograph visual calculation, sort of the cinematic equivalent of drawing arrows when playing online.

The way even the players exchange the pieces are done professionally in that sleight of hand kind of way, like a poker player fidgeting with his chips. During the director's commentary track, Gorris kept mentioning and English Grandmaster who was on set as a consultant. Later on, she eventually drops the name John Speelman, three time British Champion and two-time Candidate for the World Championship. No doubt he's the one who can take credit for the absorbing tactical combination that arises at the climactic conclusion of the film.

Turati wins Group A with a 7/9 score, and Luzhin in Group B with 6.5/9, pitting them two against one another in the championship match. Luzhin is apprehensive about playing Turati again, who suffocated him in a past engagement with an agonizing IQP position. Sasha is in search of a defense but judging by his gauntlet of facial expressions during the final game, which is rivaled only by that of a one Hikaru Nakamura, Luzhin stills finds himself lacking the initiative after all.

Luzhin eventually flags in what is perceived as a doomed position. However, I guess in this movie, flagging means that the game is just adjourned and they will continue the next day. Sasha is so preoccupied on the inconclusive position, doing his best to find a refutation, that on the car ride over he is so lost in endlessly calculating that he doesn't even recognize that Valentinov had his driver drop him off in the middle of nowhere. Fortunately for Luzhin, he's found a solution to the position but unfortunately for him, doing so triggers a nervous breakdown and he simply collapses on the spot where he's then, through an overt act of deus ex machina, is rescued by Fascist Italian soldiers. The film doesn't mention fascism in any way despite the time period being during Mussolini's rise in Italy, so there's really no need to underline this... other than the fact that in the credits the three characters are credited as Fascist Soldiers!!! This plot detail would certainly be rectified by today's standards.

There's actually a chess.com lesson on this very position in the recent 'Chess In The Movies' seven part course by NM Jeremy Kane (I swear, I had this blog idea well before that was published). You can take that lesson here -

https://www.chess.com/lessons/chess-in-the-movies/the-luzhin-defense

Or solve the puzzle of the final position below.

Can you find Luzhin's tactical refutation?

However, Luzhin never gets to play these moves himself. A combination of exhaustion and some sort of paranoid schizophrenic break after years searching for the answers of the bottomless well known as chess. The doctor lays out that chess is an addiction, imploring him to stop playing before it takes his life. A bit extravagant and metaphorical but those are the doctor's words. Valentinov doesn't care and is the ultimate enabler, showing up to the psych ward with a chess board. He wants Luzhin to finish the tournament knowing that in the physical state that he is in, he will most definitely lose to Turati.

The way story works, particularly the three-act structure that 99% of cinema (especially American cinema) abides by, the character reaches a low-point before the start of the third and final act, which is a sort of mirror opposite of how the story ends before the protagonist is finally equipped with the tools and knowledge to defeat the antagonist. However, in regards to tragedies, that mirroring is the character at their most ideal state before the rug gets pulled out beneath their feet and the hero meets their tragic downfall. This is Sasha with Natalia, finally happy and without chess, escaping those 'lost years' after his short time before he was introduced to the board game. Yet, all these outside forces pull him back in, urging him to continue his adjournment. It's a lonely battle and Luzhin can't elude fighting it. Often times, Sasha needs to be separated from Natalia, like a prized fighter holding out with celibacy as to not be distracted or consumed by anything other than the immediate objective at hand.

This idiom isn't applicable to Sasha though and is instead torn away from the life that he wants with her, involuntary leaving Natalia hanging at the alter. With no escape from Valentinov, chess or the corridors of his own mind, Luzhin decides to leap out the window and take his own life. Surprisingly, Luzhin transcribes his miraculous rook move and has Natalia, in a cheesy happy ending that I actually didn't mind (it's nice to see his genius play out on screen in a satisfying matter), play the variation against Turati herself, all while Sasha's coveted glass White king is resting next to the board overseeing the entire combination.

All in all, it's not fair to judge a film on what it isn't or if it lives up to its source material. Ultimately, a film should be able to stand on its own terms but in this case, it strays so far from Nabokov that I would imagine this remodeling would anger any fan of the more bleak and cerebral book. This uninflected love story instead just uses the Nabokov intellectual property and stripped the story from any of his signature irony. With the exception of the character's names and a few lines of witty dialogue, this story could have been, although competently made and told, essentially written by almost anyone.

![]()

![]()

![]() /5 Pawns

/5 Pawns

For a while, this film was almost impossible to find. I acquired a used copy of the DVD off of Ebay but with the exception of the commentary track, which was underwhelming, there are no special features worth your while, but I am now delighted to say that this film is currently streaming on Amazon Prime, although in very poor quality nonetheless.

Stay tuned for the next iteration of Chess & Cinema, where I'll be reviewing The Coldest Game (2019), which is currently streaming on Netflix. Feel free to tell me which chess related movies you'd like me to review in future installments by dropping a line in the comments section. I'll probably start off with lesser known/seen films until I find my form and gain my footing before tackling the grander more seen films, or at least alternate back and forth between the two. There will also be a 'miniature' series, covering movies or pop culture with chess in it but not predominately about chess. I look forward to keeping up with this blog and hearing your suggestions/feedback.

Until then, I'll see you at the movies and over the board.