A Century of Chess: Bad Pistyan 1912

What are the best single-year performances in chess history?

Just to throw out some possibilities: Paul Morphy (1858), Jose Capablanca (1922), Alexander Alekhine (1931), Mikhail Tal (1959), Bobby Fischer (1971), Anatoly Karpov (1977), Garry Kasparov (1989), Magnus Carlsen (2014).

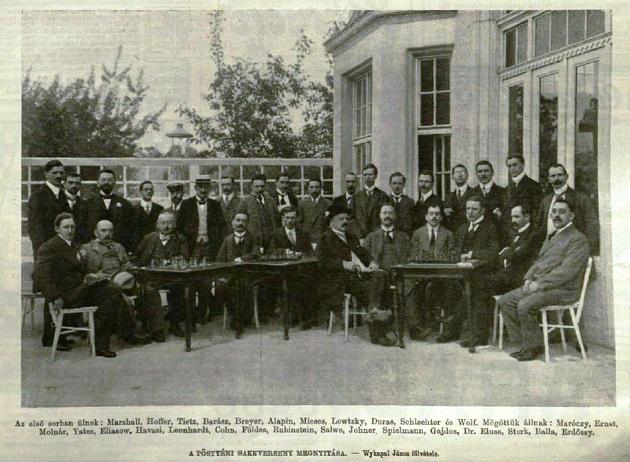

Consider also Akiba Rubinstein in 1912. Rubinstein won four international tournaments in a single calendar year, a long-lasting record. Within that year, Bad Pistyan - a strong tournament organized at a resort near Bratislava - was a crowning achievement. Rubinstein put in a completely dominant performance. He lost to Spielmann, the second-place finisher, but won 12 out of 17 games, winning the tournament by 2.5 points. Lasker responded to the Bad Pistyan victory by anointing Rubinstein "one of the very greatest masters."

Although Rubinstein is undoubtedly a great player, I don’t, to be honest, find his games all that interesting (his play becomes more well-rounded later on, in the 1920s). Really, he was an endgame expert, and it turned out that players of his era, even at the high levels, weren’t very strong in the endgame - once he exchanged pieces to a level position, he could outplay virtually anyone in the endgame, particularly his beloved rook endgames. Every so often, as in his famous games against Lasker at St Petersburg 1909 or against Nimzowitsch at San Sebastian 1912, he gets into a complex middlegame where he shows that he can hold his own, but even in his tactical play there is somehow no dynamism: he seems always to immediately cut through the complications and restore the position to an endgame where he has a slight advantage. On a couple of occasions in this tournament, Rubinstein really won games through reputation alone. For instance, Yates needlessly sacrificed an exchange to avoid going into a slightly inferior endgame. Salwe, faced with a dangerous-looking knight sacrifice in the endgame, seemed to take Rubinstein at his word and failed to calculate four moves ahead to the refutation.

I thought I was being kind of a chess philistine to think this way, but, interestingly, that was the view also of Paul Leonhardt, who played in Bad Pistyan. In an article for The British Chess Magazine, Leonhardt claimed that Rubinstein was actually a very one-sidedly positional player with pronounced weaknesses. "Spielmann demonstrated the ease with which Rubinstein could be upset by decoying him onto unknown ground and pestering him with attacks," Leonhardt said of Spielmann's victory over Rubinstein - and claimed that already, by the end of 1912, Rubinstein's opponents had figured out how to play effectively against him.

During Rubinstein’s great year, Spielmann was a fine second-fiddle, setting the pace at San Sebastian and taking second place here, winning his individual game with Rubinstein.

Marshall was in good form on his European tour of 1912, never really challenging for first place in the tournament but was always with the leading group and always played sparkling, creative chess.

The tournament is a good glimpse of a group of young Central European masters whose careers would be interrupted by the war - and many of whom would have tragic lives. Gyula Breyer is the most famous of the group. At 19 years old, he announced himself at Bad Pistyan with his inventive, strafing style - he would die at age 28 in 1921.

The Hungarian master, Zoltan Von Bella, whom I had never heard of, finished with a +2 score, including scalps of Teichmann and Alapin. He would be killed in some sort of an accident with a Soviet tank during the occupation of Hungary in 1945.

The Polish-Ukrainian player Moishe Lowcki won a brilliancy prize for his game against Duras and showed himself a credible master with a sparkling and sound style. He would be killed in a mass execution by the Gestapo in 1940.

Bad Pistyan was a good tournament for the younger generation. Curiously, the bottom three places in the cross-table were taken by established, veteran international masters - Cohn, Leonhardt, and Johner.

Sources: For Rubinstein in this tournament, the best source is Donaldson and Minev, The Life and Games of Akiva Rubinstein. Jimmy Adams' Breyer: The Chess Revolutionary includes annotations of all of Breyer's games. Photos are from Edward Winter's post on Bad Pistyan. simaginfan has a post this week on Rubinstein's magical year and including an annotation of the Rubinstein-Breyer game.