A Century of Chess: Dawid Janowski (1900-1909)

Dawid Janowski occupies something of a dubious position in chess history - he's the poor sport with the gambling problem who hated endgames, fixated on the two bishops, and somehow convinced his art swindler friend to stake him not once but twice in a disastrous match challenge to Emanuel Lasker. He also became the image of the chess-master-fallen-on-hard-times - an inveterate dandy in his glory days who showed up in New York in 1915 fleeing as far as he could get from the war and lived the rest of his life as, basically, a bum.

It's been a sub-theme of this series I'm doing on chess in the 1900s to try to rehabilitate Janowski, to make the case that he was at one stage, if not exactly world championship material, then a plausible contender nonetheless.

Janowski's peak period was from 1898-1905, which was something of a a fallow era in chess history with no world championship matches and with a small, stable cadre of elite players, and in that era he was one of the very best. He was second at Berlin 1897, third at the marathon Vienna tournament of 1898, shared second at London 1899, which emboldened him only slightly prematurely to send a world title challenge to Lasker, first at Monte Carlo 1901 ahead of Schlechter, third at Monte Carlo 1902, first at Hanover 1902 ahead of Pillsbury, second with Lasker at Cambridge Springs 1904, second with Tarrasch at Ostend 1905, shared first with Maróczy at Barmen 1905.

His play in this period really reminds me of that of Geller and Bogoljubow. Like them, he was particularly dangerous in tournaments of mixed quality. He could be dangerous to anybody, but by playing aggressively and taking risks in every game he could get on winning streaks where he would just tear apart the weaker half of the crosstable, his games, as Frank Marshall wrote, "bywords for power and elegance."

And then, around 1905, the light abruptly went out - and, to Janowski's misfortune, he didn't notice it for the rest of his life. I've never seen an explanation of what happened exactly. Looking at his games from his 1905 match with Marshall, there's something punch drunk about his play, and as the decade wore on his sense of perspective and of danger seemed to desert him completely. He finished further and further down the crosstable, was humiliated very publicly by Lasker, and then, just after he arrived in America, nearly lost a match he very badly had to win against Jaffe. As late as the New York tournament of 1924, elite players observed that Janowski was as strong and creative as anybody 'in the first four hours of play' but then would invariably overpress for a win and lose the full point. My guess of what went wrong is that gambling basically rotted his brain - as Levenfish put it, "he became too enamored with games of chance and did not have the time or patience for chess." There's something of the one-armed bandit in his play, an inveterate need to attack and to press, which can be just as deleterious in chess as in a casino. As Marshall put it: "He can follow the wrong path with more determination than any man I ever met." And Reinfeld, who had been talking to Lasker: "He had the soul of a gambler, that quality of stubborn unreason that causes a man to choose the wrong course even though he knows better. In Lasker's eyes, he was a willful child."

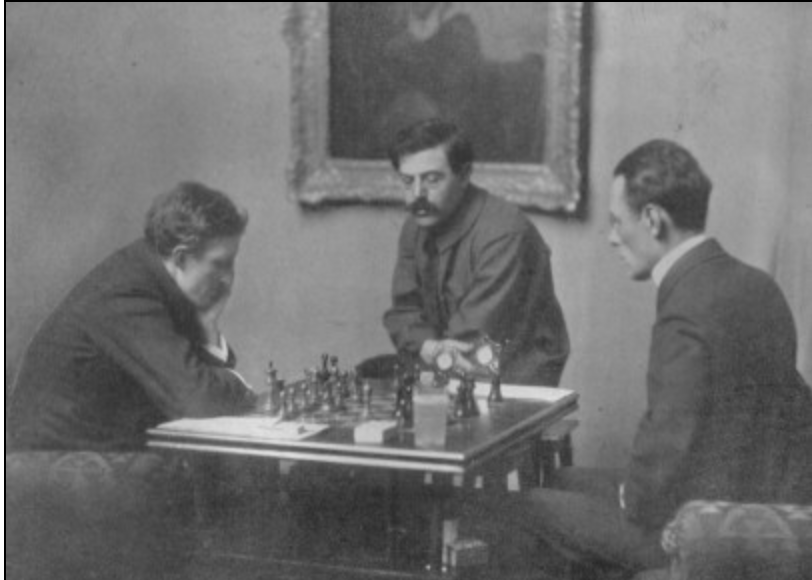

What's tough also with Janowski is the personality, and the sense here is that there was two warring selves within him. My image of him had been as a cantankerous piece of work, the guy you try to avoid in your chess club, and I was surprised to discover to see him in photographs and pen-portraits of the 1900s as the soul of elegance and courtesy. It's easy enough to spot in photographs of him - note the contrast in posture between Janowski and Frank Marshall in the photograph at the top of this post. In 1899, La Stratègie wrote: "Janowsky, by contrast, is correctness personified. Seated before his board, he remains almost totally immobile. With a dazzling shirt, Turkish cigarettes, ice-cold lemon-squash, which he sucks through a straw, he is a refined, sensitive player par excellence, a sybaritic player who may lose merely because of a rose-leaf being crumpled.’"

But, unfortunately, when he lost, Mr. Hyde would suddenly come out. After he lost the match to Marshall, he sent him a note claiming that the results proved nothing at all and challenging Marshall to a return match with Marshall given odds of four games (and, actually, Janowski nearly went on to make good on that handicap, scoring +3 in the return match). After his losses to Schlechter in their match, he turned suddenly into the armless knight at the bridge in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, and Rudolf Spielmann described how the timid Schlechter "would literally take flight so that the barrage of insults flew into empty air." But it was after his crushing match loss to Lasker in 1909 that Janowski really outdid himself - and articulated a creed-to-live-by for sore losers everywhere. "Lasker plays such stupid chess," he said, "that I can't bear to look at the board while he's thinking."

Janowski's Style

1. The Initiative.

I really believe that Janowski deserves credit as one of the pioneers of the 'initiative' - a concept that was completely absent from classical chess but is of course an essential part of the armature of every modern master. Playing for the initiative means, more or less, trying to step on the foot of a dance partner or suddenly lunging at a fencing opponent - it always involves taking some sort of a risk, voluntarily giving up something or other for the sake of activity. This willingness to deviate from the narrow strictures of Steinitzian chess made Janowski a particularly dangerous player in the first few years at the turn of the century before the chess world started to catch on to what he was doing. Most impressive of all was his willingness to sacrifice the exchange out of the opening - a look that would be familiar with the Soviet school but seemed outlandish in classical chess.

2. The Rolling Attack

Allied with the initiative was the sense of embarking on an attack before it had been fully set up - but when one's opponent was also unprepared - and Janowski's great talent was to keep pouring fuel on the fire, to organize his pieces for the attack while the attack was already underway. Janowski has a reputation for being weak in the endgame - and this is a fair critique for technical endgames and 'true' endgames - but he was strong as anybody in the conversion from the middlegame to the endgame and the ability to keep playing for the initiative even as material came off the board.

3. The Two Jans

Janowski is most famous for this - his love for the two bishops, which he named after himself. Later on, chess writers would mock Janowski for his obsession and the extraordinary lengths he would sometimes go to to secure the two bishops, but in the context of chess at the turn-of-the-century, Janowski's fixation made perfect sense. 19th century chess had tended to slightly overvalue the knight and to view the two bishops as more of a positional asset, and Janowski, like a shrewd trader, sensed an imbalance in the market: with the two bishops the future belonged to him, he could open up the position anytime he wanted and have the advantage in the resulting chaos and he could continue to play actively all the way through to the endgame.

Janowski in the Opening

Greatly in Janowski's favor was white's standard treatment of the Ruy Lopez in the early 1900s. White tended to not take the time to safeguard his light-squared bishop and Janowski in game after game picked it off with an early ...Na5 maneuver. This looked unprincipled to classical players - moving a piece twice in the opening in order to exchange it - but Janowski demonstrated that the long-term advantage of the two bishops more than made up for the loss of time. I have the sense that it was these games more than anything else that altered white's approach to the Ruy over the next century, making sure to play c3 early on and keeping the bishop safe.

Janowski's other leading contribution to the opening didn't work out quite so well - that was 3...a6 as black in the Queen's Gambit Declined. I'm not sure what's wrong with this opening idea, which seems like a subtle way of preserving a flexible development and hinting at the exchange on c4, but it doesn't score very well in practice - everything takes too long and white seems inevitably to end up with a kingside attack. Janowski went through a difficult spell playing the black's side of the Queen's Gambit around the turn of the century but showed excellent flexibility in modifying his approach. He switched primarily to a sort of deferred Queen's Gambit Accepted, getting in his favorite move ...a6 and creating long-term compensation for the surrendered pawn center with ...b5 and ...Bb7.