A Century of Chess: Maehrisch-Ostrau 1923

After his match loss to Capablanca in 1921, it would have been safe to assume that Emanuel Lasker would more or less retire. He was 52, he had always had a challenging relationship to chess competition, sometimes, even at his peak, going years without play. In 1923, a sizable contract induced him to play an international tournament at Maehrisch-Ostrau in Czechoslovakia, and there Lasker put on a staggering performance, winning eight games, drawing five, and losing none against an extremely strong field.

It was vintage Lasker, a series of daring escapes, ‘coffeehouse chess’ at the transcendent level. In an interview sixteen years later, when asked about Lasker, it was this tournament (I believe) that Capablanca chose to discuss — he remembered vividly Lasker’s win over Tarrasch:

"Instead of making the ordinary move which would have occurred to any other master, whereby he would sooner or later have lost or, with difficulty, drawn, Lasker sacrificed a pawn. But what a sacrifice! I have seen no such sacrifice in any modern games! It was impossible to know whether it should be accepted or refuted. As the saying goes, it shook the board."

This actually was the last of thirty games between Lasker and Tarrasch — one of the most famous chess rivalries of all time. The tournament was also Lasker's first encounter with Max Euwe — and Euwe's bewildering experience here may well have prompted his famous line that "it is not possible to learn from Lasker only stand and wonder."

In impressive second place, losing only in their head-to-head matchup, was Richard Réti, who had now settled into the most adamantly hypermodern phase of his career. He opened all of his games as white with 1.Nf3 and played the opening with a kind of sleepy approach, fianchettoing his bishops, taking queenside space when possible, waiting for an opponent to commit to a fixed pawn structure, and then either seizing the center or working around it as best suited him. Tarrasch, in one of his withering salvos against hypermodernism, wrote of Réti’s game against Grünfeld, a nearly symmetrical draw:

"Supposing that the opponent also adopts the same petty and cowardly strategy and holds back his central pawns, what then? Then there is no question at all of struggle, since the two armies do not meet! Let the following absolutely horrible game, played in the Maehrisch-Ostrau tournament of 1923, serve as an example. The names of the players I will keep secret."

But Tarrasch was cherrypicking his evidence. The game was a last-round ‘grandmaster draw,’ and Réti’s style led to excellent fighting chance as well as a few startlingly easy wins in which he seemed never to exert himself or compromise his position.

I have the odd sense playing over the game of Maehrisch-Ostrau that I’m seeing, in encapsulated form, some of the standard tropes of club chess over the next century. There’s a certain type of local master who has fully absorbed Réti’s style from Maehrisch-Ostrau, forgoing a bid either for the center or for spatial advantage, harmonizing pieces within his own ranks and waiting for an opponent to overcommit. If this style had existed before — notably in Lasker’s play — it became somehow codified with Réti.

Ernst Grünfeld, who was at his career peak, finished a strong third. The almost completely forgotten Alexey Selezniev had the strongest event of his career, taking fourth — he was one of the ‘Mannheim players,’ interned in Switzerland throughout World War I. He returned to Russia in 1924 and then, with the help of his friend Bogoljubow, was expatriated to Germany during the war, eventually settling in France. He was mostly noted as a composer. The tournament was an important watershed for 22-year-old Max Euwe, who had had decidedly mixed results over several international tournaments and seemed fated to be a strong ‘local’ player like Fred Yates or Karel Treybal. But at Maehrisch-Ostrau, Euwe had a breakthrough at least from a stylistic point of view, winning staggering games against Rubinstein and Wolf, in both of which he sacrificed his queen and won with the expert harmonization of his minor pieces.

On the other side of the crossable, Rubinstein continued his decline, posting a losing score for the second tournament in a row, although he had the consolation of a brilliant King's Gambit victory.

Bogoljubow, who had become one of the world’s most terrifying tournament players, only managed an even score. Tarrasch looked at sea in several of his games but won the brilliancy prize for a lovely win over Spielmann on the black side of the King’s Gambit. Spielmann (who also scored poorly) was so unnerved by the game that he wrote an article speculating that the King’s Gambit might finally have been refuted — and Tartakower agreed that the King's Gambit had to be "tossed in the junk room."

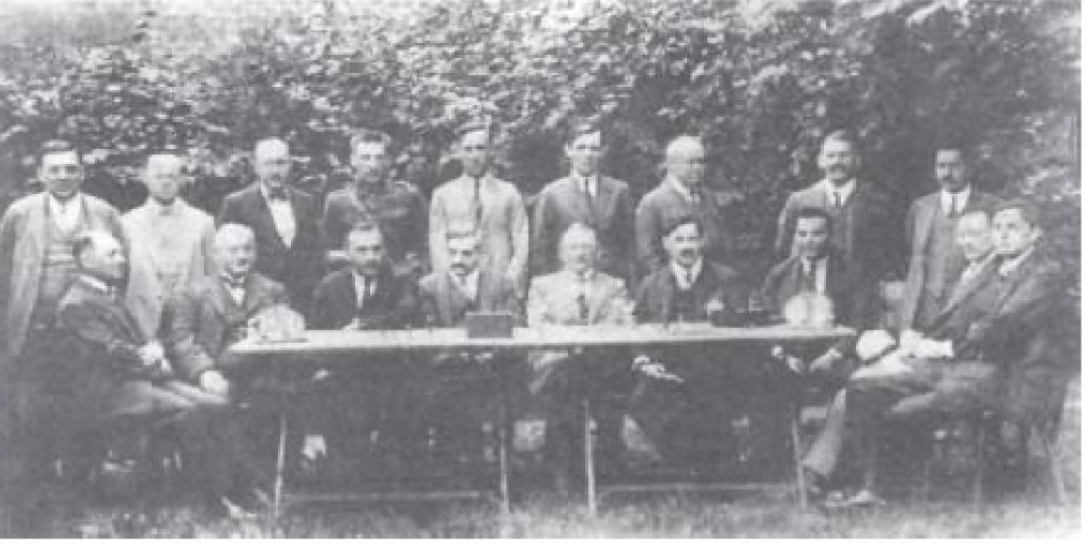

In terms of chess history, the tournament is significant also as the setting for David Friedmann's sketches of the leading players of the era (see above). Friedmann — a native of Maehrisch-Ostrau — was an accomplished lithographer, and his sketches (the originals taken from him by the Gestapo and in many cases painstakingly tracked down after the war) are among the enduring legacies of the classical era.

Sources: The tournament is extensively discussed in Tartakower's Hypermodern Game of Chess and Soltis' Why Lasker Matters.