A Century of Chess: New York Masters 1911

Capablanca's ascent to the chess stratosphere seems so foreordained that it's easy to forget that there was an extended period of time in which he wasn't the world champion designee, in which he was, essentially, a rumor - a super-talented Cuban kid who was basically busy with other stuff, school and sports, etc. And, to a startling extent, it was one person - Frank Marshall - who made it possible for Capablanca to leap straight from the periphery to the chess elite. In 1909, Marshall agreed to play a match with Capablanca, lost to him shockingly, but then, in one of the great-ever instances of chess sportsmanship, put in a recommendation for Capablanca allowing him, over the objections of other masters, to play at San Sebastian 1911, which Capablanca won and which made him instantly a world championship challenger.

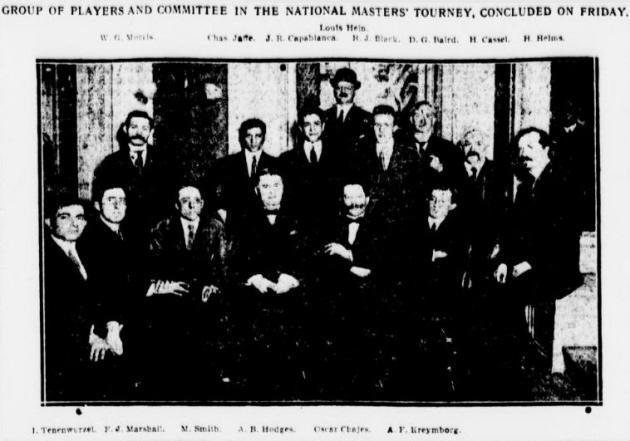

But Marshall was a great competitor as well and he had two chances for revenge - eclipsing Capablanca in tournaments at New York 1911 and at Havana 1913. Neither one was a particularly notable achievement - the field of North American masters wasn’t so strong - but Marshall showed Capablanca that there was still a thing or two to be learned about playing tournament chess. In the case of New York 1911, he smoothly ran the table, while Capablanca had some trouble with his opening inexperience - he tried a Sicilian Wing Gambit against the New York master Roy T. Black and was duly punished.

The tournament is like a last chance to glimpse Capablanca while he’s still a regular chess player, before he becomes the chess deity that he’ll remain for the rest of his career. And, looking at the New York games, it’s something for a surprise actually that he ascended so quickly. His openings really were very weak. Other than the Wing Gambit, he seemed to fall onto safe, congested positions as quickly as possible and then to trust in his middlegame skill to sort himself out of a jam. None of his New York wins are particularly striking, but he was for the most part up against weak competition who seemed to go to grief of their own devices.

This is a nice moment to introduce the rest of the band - the New York masters who will be Capablanca and Marshall’s lone viable opposition in North America for the next decade. Oscar Chajes was a Galician immigrant, a solid positional player and 'East Side idol,' whose claim to fame was that he was the last player to defeat Capablanca in a tournament game (in 1916) before Capablanca's eight-year lossless streak.

Charles Jaffe was a different story - the prince of the Bowery and the quintessential hustler. Everybody found Jaffe amusing - he brought a courtroom to stitches when he appeared on the witness stand in a lawsuit and ran down the abilities of all the other expert witness as being unqualified to speak on chess matters; a pair of muggers tried to hold him up and were so taken by Jaffe's nonchalant response - he invited them to search him and let him know if they found any money on him because he sure couldn't - that they bought him a drink. Capablanca world end up blackballing Jaffe from top-level American chess, which really is too bad. Jaffe was one of these street players who could mix it up with the world’s best. And, actually, the New York tournament was bon voyage for Chajes and Jaffe as well as for Capablanca - they were playing at the prestigious Carlsbad 1911 tournament, and Jaffe had taken out a considerable subscription to finance himself, but their failure there would mean the end, unfortunately, of their international careers.

The tournament assumes its primary place in chess history as the basis for Alfred Kreymborg’s essay/memoir 'Chess Reclaims a Devotee.' The piece was the standout of Burt Hochberg’s anthology The 64-Square Looking Glass and is one of surprisingly few literary-minded pieces on competitive chess from the perspective of high-level players.

Kreymborg had a nightmare loss in the tournament. He had a brilliant combination against Oscar Chajes, involving a queen sacrifice proffered in three different ways. As he wrote, "No one spoke to anyone else but I could see the experts nudge each other and eye me amazedly. Capa and Marshall had been forgotten. I was the center of the chess world and I paced up and down the dark ring, a prey to frenzied emotions."

And then the pressure got to Kreymborg. "My hands began shaking with each successive move," he wrote. Finally, Chajes made his move and the ring around the board opened up. "A number of men looked my way and respectfully opened a path," Kreymborg continued. "Capa was one of the men who stepped aside. I could see him smile a little." But Kreymborg, striding to the board and not even bothering to sit down, mixed up the moves in his combination and his blunder allowed Chajes to escape and then to win. According to his account, the loss was, essentially, the end of his chess career. He fell to the bottom of the crosstable at the New York Masters and dedicated the rest of his working life to his other calling, modernist poetry.

I’ve been particularly curious about Kreymborg because he seems to be a contender for a curious distinction - some sort of G.OA.T. award for the individual who was, at the same time, the strongest chess player and the strongest writer. My suspicion is that Frans Bengtsson (the author of The Long Ships) would edge out Kreymborg in the writing department and break about even with him in chess while Nabokov wasn't quite at the same level of competitive chess. But this speculation has sent me diving around Google for some of the long-forgotten writing of Kreymborg.

It turns out that he had more of a reputation as a generous promoter and editor than writer. He was integral to the modernist scene, intertwined with Wallace Stevens, William Carlos Williams, Ezra Pound, Carl Sandburg, etc, and has been given credit as the discoverer of Marianne Moore. I have to admit that I found his poetry to be in a slightly indeterminate place, caught between the older, rhapsodic Victorian style and the fresher modernist impulse. But his prose is very readable and there is this sweet poem, which conveys, I think, something of his spirit.

I’m sorry to not be nicer to Kreymborg’s writing. There was something about him that seemed, for no very clear reason, to being out the cruelest in people. Julian Symons said that he was a prolific critic but "never an interesting one." Richard M. Elman wrote a really mean-spirited essay about an encounter with him in the 1960s. Elman described him as "undifferentiated," "a man with glasses and a wilted brown mustache who had been very much overlooked, like an old family ghost," and called him a "has-been" - although one would think that anybody in their 80s would to some extent be a 'has-been.' There is a much nicer tribute to Kreymborg here, in which he is described as being "one of those of his age who stands for freedom in form" and is viewed as being a critical bridge figure to the modernist sensibility.

Sources: 'Chess Reclaims A Devotee' is the most interesting piece on the event. There's an impressive entry by Edward Winter on Kreymborg. The tournament is discussed in various Capablanca writings, including My Chess Career. Marshall's writing is from Marshall's Best Games of Chess.