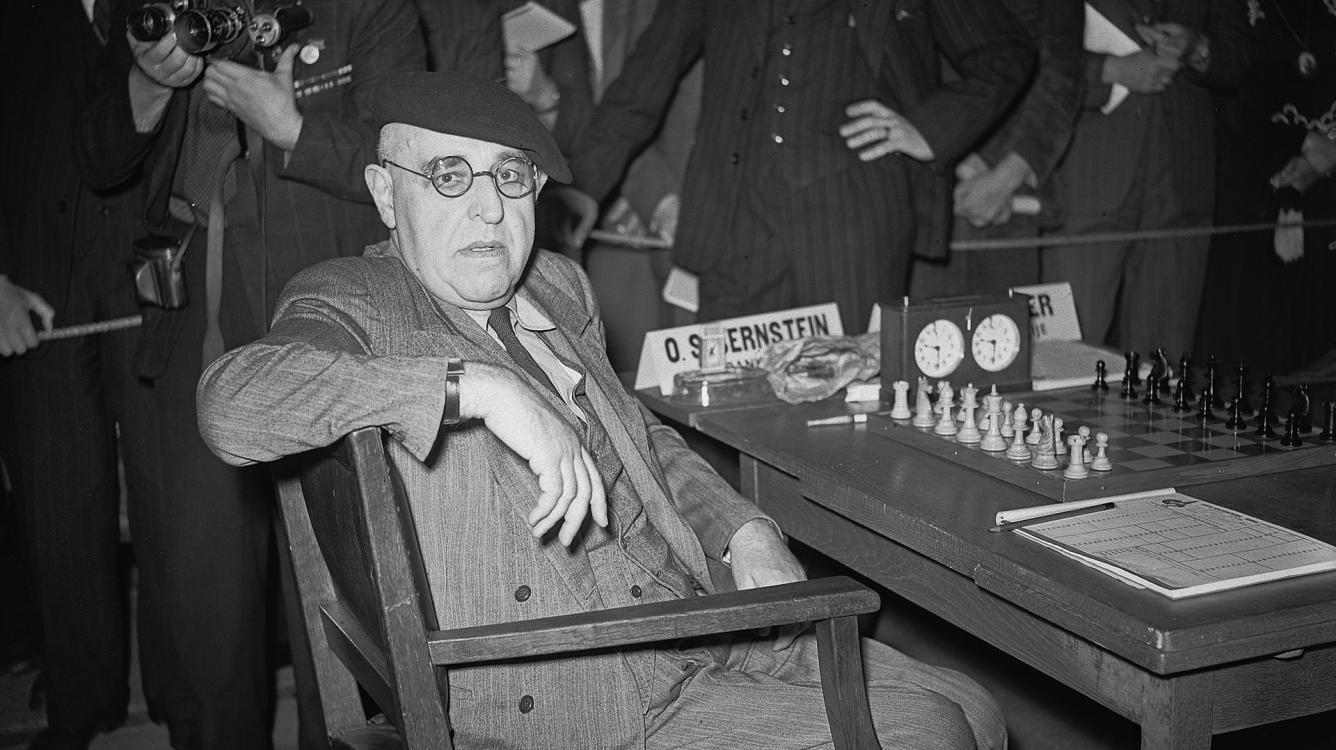

A Century of Chess: Osip Bernstein (1900-1909)

At the moment I’m moving through players of the 1900s in reverse order of how they appear on a rainy-day imaginary tournament I put together of the top 16 players of the decade. Osip Bernstein was the great surprise of that oddly engrossing activity - finishing in third place.  As I said in my post presenting these results, I wouldn’t necessarily take them too seriously. Bernstein benefited from the constraint I put on the event. His peak period was exactly in the decade between 1900 and 1909 and at that time he was like a talented rookie tearing up the league. By the time the top players got another look at him in the 1910s he wasn’t quite as overpowering - at the super-elite tournaments of San Sebastian 1911 and St Petersburg 1914, he was a credible participant but certainly not the best player present.

As I said in my post presenting these results, I wouldn’t necessarily take them too seriously. Bernstein benefited from the constraint I put on the event. His peak period was exactly in the decade between 1900 and 1909 and at that time he was like a talented rookie tearing up the league. By the time the top players got another look at him in the 1910s he wasn’t quite as overpowering - at the super-elite tournaments of San Sebastian 1911 and St Petersburg 1914, he was a credible participant but certainly not the best player present.

Still, he was world-class and from as early as 1905 was talked about seriously as being a worthy challenger for a world-championship match. To the extent that he’s remembered at all now it’s for the macabre story of playing chess for his life when faced with Cheka execution during the Russian Civil War, and it’s easy to lose sight of him as a charter member of the pre-war chess elite and above all as the shining light of the sturm und drang generation that shook up the classical chess world.

Tartakower, who appreciated Bernstein more than anybody, described this as "the generation that Bernstein, robust and imaginative, inaugurated at Barmen 1905." The philosophy of this approach was very simple - chess was to be treated as a struggle. The theory of the classicists and the scientific school was all good and well but its disciples tended to forget the main point - that chess was about winning and about taking the fight to one’s opponents. Because Nimzowitsch and Réti codified the strategic breakthroughs of the 1910s as ‘hypermodernism,’ that perspective - of chess as an ornate strategic struggle, of a new ‘cubist’ aesthetic in chess - prevails whenever one thinks about this period. But to players like Tartakower, Spielmann, Bogoljubov, etc who went through this pivotal moment - the shift from classicism to the next turn of the wheel - it was really the spirit of Bernstein that mattered most, an interest in chess as sport rather than chess as art, an attention to the specifics of the fight as opposed to the eternal principles of the game.

Bernstein grew up in Zhitomir, near Kyiv. He started playing competitively around 1902 and was instantly understood to be a top player with his skirmishing style and sharp tactical eye. He defeated Chigorin in their individual game at Kyiv 1903 and finished in second place at the tournament.

In 1905, he finished fourth at Barmen. This was really a startling achievement in the context of that time. There simply hadn’t been a new player breaking into the elite since Frank Marshall in 1900. The chess world had come to be a cozy scene of predominantly German-speaking players taking turns with tournament victories. With Bernstein, the dam broke, and suddenly a range of players from a wide variety of backgrounds were challenging the ‘grand panjandrums’ for tournament prizes. Bernstein followed up Barmen by spoiling Maróczy’s near-career-defining tournament at Ostend 1906 and then finished shared first with Rubinstein at Ostend-B 1907.

And then somewhere in the later half of the decade Bernstein got serious about his legal career and drifted away from chess. In this, he’s very much the classical equivalent of Maxim Dlugy - or Mikhail Najdorf might be the mid-century counterpart - the prototype of the chess master as cardsharp, a player with a good analytic mind, strong nerves, a gift for the struggle, and who is equally able to apply those talents in more lucrative professions. That’s the somewhat far-fetched principle that makes schools sponsor chess programs - that it’s a good tool for analytic training - as opposed to the near-mystical view of chess as art that appears in the play of somebody like Rubinstein or Schlechter.

And Bernstein’s personality went with his approach to the game. He was a great kidder, with a somewhat heavy sense of humor, and a skilled raconteur. This gift for the gab makes the almost-shot-by-the-Cheka story a little suspicious, but people who heard Bernstein tell it claim he was absolutely convincing in laying out the scene, describing how his hands shook as he moved the pieces.

Bernstein's Style

1.Skirmishing

I remember playing a table top war game in which battles were fought according to a set of pre-determined strategies. There was ‘charge,’ ‘outflank,’ ‘bombardment,’ and then there was an enigmatic card called ‘skirmish.’ That’s how I conceptualize Bernstein’s play, a sense of engaging in battle all across the line and looking to win through tactical flurries in which the more nimble antagonist prevails. Grischuk very much has this style, also Najdorf, Reshevsky, Browne, Korchnoi. Lasker is of course the godfather of this supremely-pragmatic approach, so the question becomes whether Bernstein was modeling himself on Lasker or going off in his own direction. But the consensus of the era seemed to be that Bernstein represented something new - a fresh wind - which may have been about belligerence all throughout the game whereas Lasker sometimes seemed to only start playing once his opponent had an initiative.

2.Encroachment

Bernstein's style is a little difficult to talk about. It's the sort of skills that never get discussed in classical handbooks - more tricks of the trade than higher chess truths. Andrew Soltis does a good job of analyzing these aspects of the master's toolkit in What It Takes To Become A Chess Master. It's ideas like 'more' and 'enough' - just a very subcutaneous sense of the balance of a position and then an ability to grab even the slenderest of advantages. One slightly more concrete quality of Bernstein's is 'encroachment' - a tendency to constantly look for ways to invade the opponent's half of the board, adding on psychological and tactical pressure even if the incursion isn't objectively so dangerous.

Bernstein in the Opening

I was really unaware of any contribution of Bernstein's to the opening, but it turns out that his name is on a variety of lines - in the Giucco Piano, Queen's Gambit, and above all in the Open Ruy Lopez. Tartakower, who is unstinting in his praise of Bernstein, calls him "the brilliant opening artist." His innovations tended to be in modern style - novelties deep in existing lines. The impressive win below against Teichmann is indicative of his approach to the opening. The retreat of his pieces around move 10 is as bit similar to David Bronstein’s somewhat whimsical strategic dictate that a player try to keep his pieces from being attacked in one turn. From that stance of flexibility, Bernstein is then able to uncoil rapidly and to keep pressing into Teichmann’s position.

Sources: Almost everything about Bernstein online is connected to the Cheka story. He is mentioned very favorably in primary sources like The British Chess Magazine and Lasker's Chess Magazine. Tartakower's The Hypermodern Game of Chess has the lengthiest discussion of his contribution to chess history.

Plugs: As usual, I'm talking up my Substack 'Castalia.' Posts this week include 'the non-fiction novel,' the short story 'Afterlife,' discussions of Jaron Lanier, Tommy Orange, analytic philosophers, the CIA's literary fronts, etc.