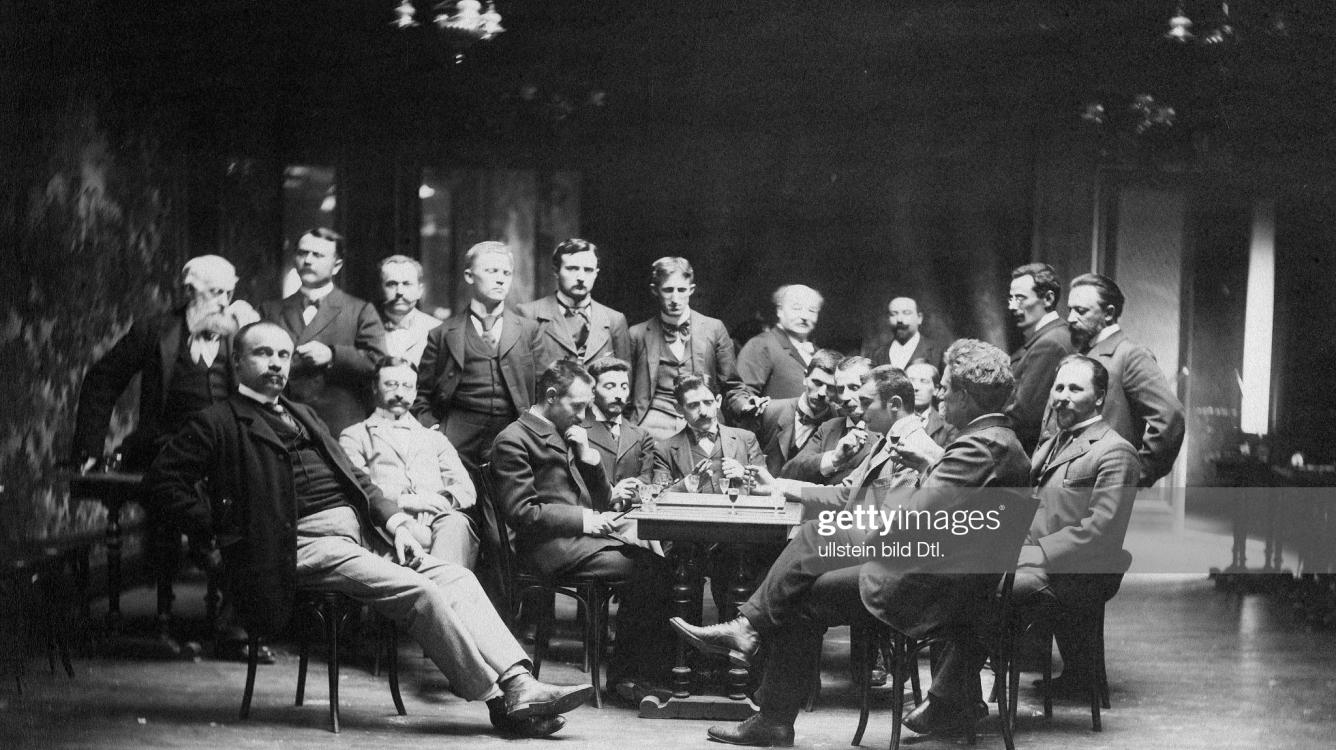

A Century of Chess: Paris 1900

A gorgeous start to a century of chess. The tournament was held as part of the World’s Exposition in Paris and included all of the top players of the era with the exception of Tarrasch and Teichmann. The Exposition was a manifestation of the giddy optimism of the turn of the 20th century - it featured one of the early Olympic competitions, the advent of art nouveau as a style, various showcase buildings including the Musée d’Orsay, and competitive events including pigeon and balloon racing – and the international chess tournament was part of this carnivalesque mood.

The mammoth London tournament of the year before (27 rounds!) had been a race between Lasker, Pillsbury, Janowski, and Maróczy, with Lasker eventually outdistancing the field by 4.5 points, and Paris had a very similar texture. Lasker repeated his success, winning 14 games against a loss and a draw while his rivals fell off one by one.

Lasker was in the process of distancing himself from tournament chess – he would play in only one more tournament in the next nine years – but the twin victories at London and Paris demonstrated to a somewhat skeptical chess world how dominant he truly was.

I find it useful in playing over Lasker’s games to forget almost everything you think you know about him – the canard about psychology and about playing ‘intentionally bad moves.’ Here are a few general observations. He played the opening a bit riskily, fishing for imbalances. If he achieved an advantage, he was perfectly capable of playing simple master’s chess, pocketing a pawn and converting it in the endgame (as in the game with Marco annotated here) or whipping up a powerful straightforward attack. If his opening backfired, as often happened, he adapted immediately to the situation and played a shrewd ‘lurking’ defense in which he looked for the right moment to counterattack (as in the game with Schlechter below). What differentiated him from any of his rivals was his ability to play with versatility in any type of position, especially positions out of the realm of the classical school of chess: queenless middlegames, ‘skirmishing’ tactical positions, positions with profound asymmetries. He sensed that chess was more complicated and multi-faceted than probably anyone else of the era suspected – and even ‘inferior positions’ contained myriad resources.

Pillsbury was Lasker’s chief rival at this point and he tore through the field at a similar clip. It’s clear that the two of them were in a class by themselves – the only two who really understood dynamic chess – although Pillsbury didn’t quite have Lasker’s magic touch for finding possibilities in even the least promising-looking positions.

Their head-to-head game is a beauty to play over, Lasker gaining a significant advantage twice, Pillsbury constantly fighting for dynamic chances, but Lasker emerging with the better endgame.

The self-confident Janowski had taken his second-place finish at London 1899 as a cue to challenge Lasker for the world championship. He started Paris with six straight wins, but losses to Pillsbury and Lasker demoralized him and he sank out of contention – he wouldn’t have the clout or opportunity to challenge Lasker for another decade.

Playing over the games, I was surprised at the relatively weak play of Géza Maróczy, who was nowhere close to the strength he would have a few years later. His tournament result was solid enough, he finished shared third, but he looked hopelessly overmatched against both Lasker and Pillsbury. Of the other stars who would dominate the next decade, Carl Schlechter was still not quite the player he would become – he was still in his ‘Viennese drawing master’ phase. He would have his breakthrough at Munich later in 1900.

The tournament is, however, best remembered for the arrival of Frank Marshall. Marshall, at 22 years old, was very much a minor, unknown player, and, despite sailing to Britain the year before, hadn’t been allowed into the main tournament at London 1899.

He sailed to Paris the next year, sensing, as he later wrote, that “my entire chess career might depend on the showing I made in this tournament.” At Paris, he defeated both Lasker and Pillsbury and finished shared third – would have taken second if not for a last-round loss to Maróczy.

As it turned out, Marshall still had growing pains ahead of him – he would have a long string of middling results before his ‘year of years’ in 1904. It’s a recurring feature of chess history for a little-known American player to voyage to Europe, sweep all opposition before him, and completely change the landscape of chess. That was the story of Morphy in 1858, Pillsbury in 1895, Capablanca in 1911, Fischer in 1958 (maybe also Carlos Torre in the mid-‘20s and Reuben Fine in the mid-‘30s) and Marshall’s Paris début belongs to that pattern. It’s easy to overlook Marshall because he turned out to be a cut below the world’s very best, but he was truly a wonderful player, consistently in the world’s top five or ten for the next 25 years, playing always with flair, creativity, and a palpable love for the game.

An odd feature of this tournament was the rule all that all draws were to be replayed, making a 16-round tournament that much more exhausting. (The 1900s were ‘a great decade for experiments,’ as Marshall drily remarked.) From a theoretical point of view, the tournament was notable for the advent of the Queen’s Gambit Declined as an attacking weapon. Pillsbury had paved the way with a number of notable wins in the 1890s, but Marshall brought the opening into overdrive, attacking black’s king straight out of the opening. He won a famous miniature against Burn – a 18-mover with an attack along the h-file. Less well-remembered is his game in the next round, in which Marco – the leading theoretician of the period – took the black side of the same variation and did find an improvement on Burn’s play but lasted only until move 23.

Compared to the play of a few years later, when the ‘classical style’ had ossified, the chess of this tournament seems fresh, buoyant, a bit naïve – aggressive lines that were virtually to disappear, like the Dragon Sicilian and the Open Ruy Lopez, were still popular, and it’s fitting that the critical game of the tournament, between Lasker and Pillsbury, was a Staunton Gambit.