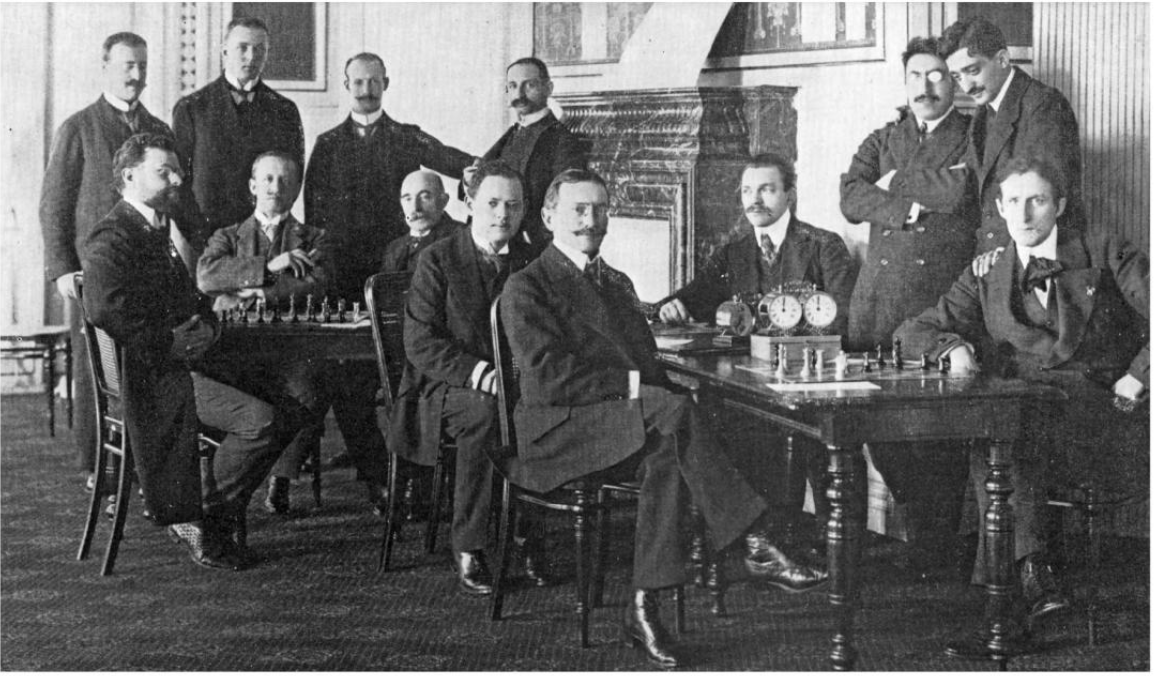

A Century of Chess: San Sebastián 1912

The premier tournament of its time. San Sebastián 1911 introduced Capablanca to the international chess scene. The tournament’s second incarnation didn’t have quite the same drama - Capablanca was unavailable to play - but it was a truly elite, hard-fought tournament. The pace was driven successively by two of the Young Turks - Rudolf Spielmann and Aron Nimzowitsch. Spielmann led by two points at the end of the tournament’s first half, winning his games in a torrent of combinatorial play.

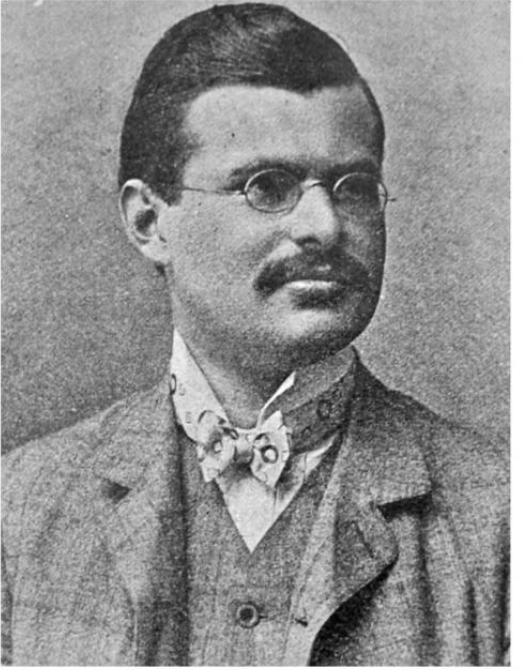

He faded badly, and was caught by Nimzowitsch, with Rubinstein and Tarrasch close behind him. In the last round, Nimzowitsch played Rubinstein, needing only a draw to take first place. With black, Nimzowitsch initiated a dubious attack out of the opening. Rubinstein fought it off, seemed to be consolidating the position. Then, on move 25, in an extraordinary case of double-blindness, both players missed a mate in two - and Rubinstein went on to collect the point and first place.

It was the start of Rubinstein’s annus mirabilis of 1912 - he had four first-place finishes in international tournaments that year, setting a long-standing record.

Nimzowitsch had been an elite player for a half-dozen years, but San Sebastián 1912 was the first true indication that he might be a world title contender. Nobody yet was calling his style ‘hypermodern,' but it was clear that his approach was very different from classical chess (and, for Siegbert Tarrasch, who detested him, "it would have been absolutely scandalous if his unaesthetic play had secured first place").

Interestingly, in his notes on the tournament, Capablanca viewed both Nimzowitsch and Spielmann as a sort of retro development - "the brilliance of the old school under the theory of the modern school." What was obvious as well with Nimzowitsch was his liking for creaky openings - "bizarre but deeply thought out maneuvers," as Jacques Mieses put it. In San Sebastián, unlike his tournaments in previous years, he seemed less interested in a gradual positional encroachment of his opponent’s position and more in dynamism - creating attacking chances out of a constricted position.

The tournament was also the high-water mark of Julius Perlis, who would die the next year. He finished fifth and played in his pellucid style.

Teichmann, who had been the winner at Carlsbad 1911 and seemed to be coming into his own, instead lost his ambition and contented himself with 16 draws. Schlechter had more or less the same strategy, drawing 14 games. He had been superb in tournaments in 1908-1911, but an eighth place finish here indicated that he might have passed his peak. I have no great excuse for choosing to show a game of Duras, who had a mediocre tournament, but I just get really obsessed with his play.

Sources: For Rubinstein's role in this tournament, the best source is Donaldson and Minev, The Life and Games of Akiva Rubinstein; for Nimzowitsch, it's Skoldager and Nielsen's On The Road To Chess Mastery. The tournament was widely covered in the chess press at the time, and annotated versions of these games can be found all over the internet.