A Century of Chess: St Petersburg 1914 (Part 2)

Capablanca started the finals of the 1914 At Petersburg tournament with a commanding 1.5 point lead. He had put on a master class in the preliminaries. His biographer Miquel Sanchez wrote, "It is difficult to find a collection of games of such serene harmony as those played by Capablanca in the preliminary round at St Petersburg." And he continued his wonderful form into the finals. He won smoothly with black against Tarrasch, grabbed a pawn in the opening against Marshall and then converted it to a win with apparent effortlessness. In his first encounter with Lasker in the finals, he tortured him for 100 moves before Lasker emerged with the draw.

Meanwhile, Lasker struggled through the tournament’s preliminary round and needed wins in his last two games to be sure of qualifying. He seemed to be playing rope-a-dope chess, staying narrowly in the drawing window in both his games with Capablanca and in particular with a miracle save in a game against Tarrasch. But, like a great long-distance runner slowly reeling in a rival, Lasker in the finals managed to gain ground on Capablanca’s scorching pace. He won a complicated tactical skirmish against Alekhine in a game in which for long stretches it was unclear who was better; kept a cool defensive head against a deep combination from Marshall; decisively outplayed Tarrasch in his beloved Tarrasch Defense; rewrote endgame theory to take the full point from Alekhine in a two rooks vs rook and knight endgame that was supposed to be a theoretical draw.

The decisive confrontation came in round seven with Lasker still trailing Capablanca by a full point. The game - one of the most famous ever played - is actually not a very good game. Lasker has been given credit for a variety of psychological masterstrokes. Richard Réti wrote that his selection of the Spanish Exchange Variation was a cunning way to throw Capablanca off-balance - since Capablanca would have wanted a draw, and, in the Spanish Exchange, black, to achieve equality, has to play aggressively. "The choice of the colorless opening was an ingenious master stroke: it was a psychological attack on his opponent," wrote Ludek Pachman, echoing Réti's analysis.

Actually, the game was a bit more a reflection of Capablanca’s overconfidence than Lasker’s cunning. Capablanca had gone so long without losing that he seemed to have forgotten that that possibility existed. Sergei Prokofiev, a visitor to the tournament, described him as "having the easy grace of one who already knows himself to be the victor." With the admittedly-somewhat-discombobulating 12.f5, Lasker was making the fairly transparent positional threat of Ne6, which Capablanca somehow overlooked. Faced with an unfavorable opening, Capablanca failed to switch into drawing mode - not only did he neglect to exchange off the knight but he opened up both the a and h files, which turned out to be highways for white’s rooks. At the end of the game, Capablanca, as his biographer Miquel Sanchez wrote, sat at the board for long minutes with his head in his hands. Meanwhile, as Lasker recalled, "From the several hundred spectators there came such applause as I have never experienced in all my life as a chess player. It was like the wholly spontaneous applause which thunders forth in the theater, of which the individual is almost unconscious."

It was in a sense the defining moment of his career, 45 years old, having not played a competitive game since 1910, and nonetheless in a high-pressure situation able to decisively beat the greatest chess genius who had ever lived.

What everybody forgets about St. Petersburg 1914 is that there were still four rounds to play after the Lasker-Capablanca game. In the next round, Capablanca - who had never before and would never again lose consecutive games in a tournament - made probably the worst blunder of his career to that point, a case of wrong rook, and was lost out of the opening.

That led inevitably to the thought that Capablanca had a glass jaw - couldn’t withstand adversity - and he seemed on his way to a meltdown when he fell into a Marshall trap and lost a piece. But part of Capablanca’s armature as a great player was his ability to play from losing positions and he somehow managed to outfox Marshall in the endgame and take the whole point.

Meanwhile, Tarrasch held his old rival Lasker to a draw, and that set up a final round with the situations reversed and Capablanca chasing Lasker. Capablanca did his part, staying a tactic ahead to defeat Alekhine in a strafing sort of game, but Lasker prevailed without difficulty against his ‘client’ Marshall - with Marshall overlooking a fairly simple tactic and walking into a mating attack.

There was more good cheer for Lasker. At the farewell banquet, his wife suggested that he make peace with Capablanca - ending a feud they had had since a failed match negotiation in 1911 - and he initiated that by drinking the health of Capablanca and shaking his hand. This really touched the sensibilities of the assembled Russians and, as Lasker recalled, "Then the diners became frenzied. They crowded around us, and then around Mrs. Lasker, hailing her as the peacemaker."

The tournament was of course big on ceremony. That did not, though - sorry to say - include the bestowing of the grandmaster title by the tsar on the five qualifiers for the finals. The tsar, who was close to the tournament organizers, was not in St Petersburg at the time, and the story seems to be a concoction of Fred Reinfeld from the time he co-wrote Frank Marshall’s memoir in the 1940s. But the story is sort of spiritually true and has come to be gospel in chess circles for where the grandmaster title comes from - giving it a pleasantly royal tinge.

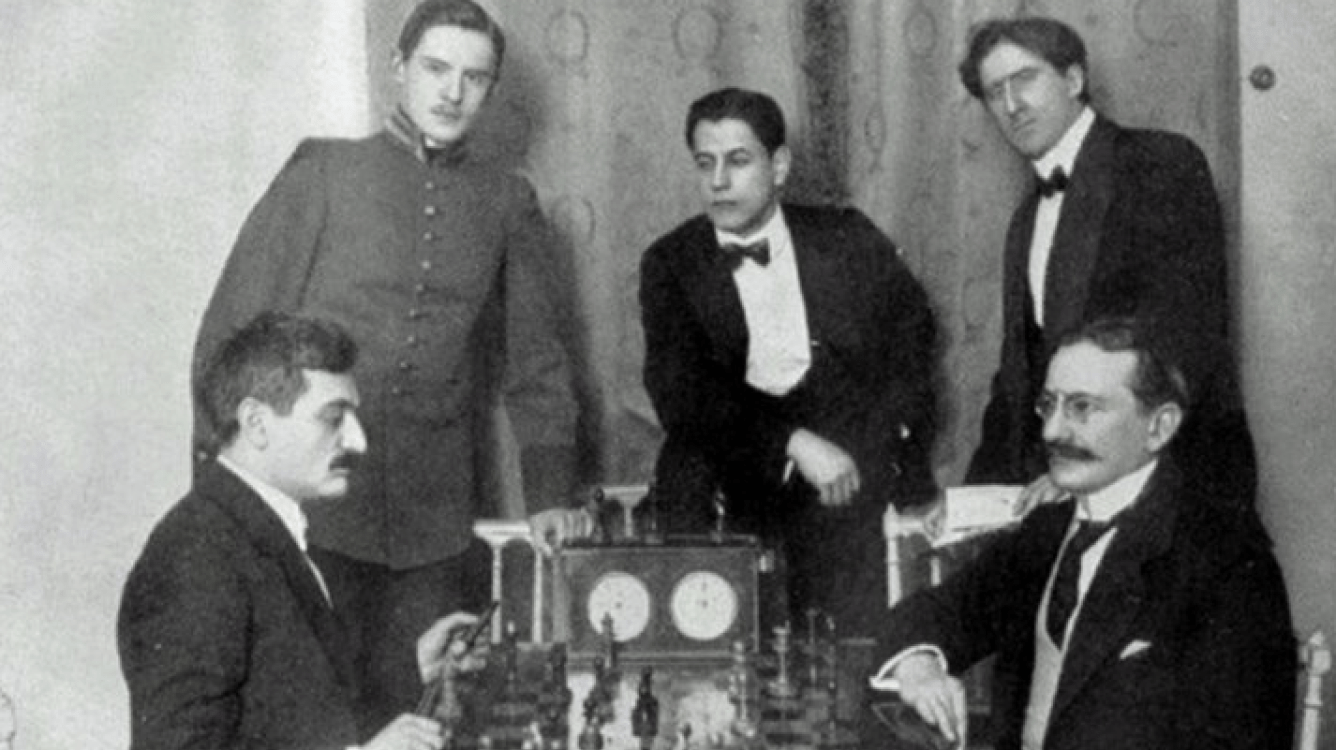

As for the other qualifiers, the old warhorses Tarrasch and Marshall broke down, unfortunately, when faced with Capablanca/Lasker/Alekhine close to their prime. Tarrasch also managed, to some extent, to quell his long-standing rivalry with Lasker. In the tournament book, he wrote, “But then almost every game of Lasker’s in this tournament is worthy of a world champion” - a very generous comment for someone who had spent years accusing Lasker of usurping the title. Grigory Levenfish, who was assisting the tournament committee, wrote that "The big surprise of the tournament was Alekhine's third place finish. No one was placing any special hopes in him, but it became obvious that he was moving into the first rank of grandmasters." He was still clearly outclassed by Capablanca and Lasker, scoring +0=2-4 against them but was +6=6-0 against all the tournament's other competitors. The surprise, playing over his games, was how many risky opening lines he selected - the King's Gambit, Albin Counter-Gambit, and 'Alekhine's Folly' in an important game against Capablanca.

Sources: Capablanca discusses the tournament in My Chess Career and in Chess Fundamentals. The tournament features in ever biography of Lasker's - the best one is Soltis' Why Lasker Matters. Levenfish has a nice memoir of the tournament here and Prokofiev here. Edward Winter thoroughly discusses the tsar/grandmaster myth here.