GM William Lombardy, 1937-2017

[Note: Updated with extensive thoughts from Lombardy's only son Raymond and a personal reflection from Bruce Pandolfini.]

GM William Lombardy, an American former world junior champion also made famous for being GM Bobby Fischer's second, died Friday in Martinez, California.

His death was confirmed to Chess.com by friend Joseph Shipman, who had visited Lombardy one week prior in Berkeley, California. Joseph Shipman, the son of the late IM Walter Shipman, who also died this year, spoke with the police officers that were on site and the coroner. Shipman reported that Lombardy "collapsed and died."

Lombardy had only recently moved to California after a well-publicized eviction from his New York apartment. He had been living with friend Ralph Palmieri, according to Shipman.

(Left to right) Jerry Spann, Raymond Weinstein, and William Lombardy on the way to the historic 1960 World Student Team Championship in Leningrad. Photo courtesy US Chess Federation.

Lombardy was born in Manhattan in 1937 to parents Raymond and Stella. He grew up in the Bronx and lived most of his life in New York until his final years. He was also a Catholic priest during his prime playing years. He participated in seven Olympiads for the U.S. and won a gold medal in 1976. All told, Lombardy compiled four Olympiad team medals (one gold, one silver, two bronze) and one individual gold medal (1970).

In the 1957 World Junior Championship, held in Toronto, Canada, Lombardy finished with a perfect 11/11 score. He became the first of six Americans to win the title, but no one before or since has managed an unblemished score.

That 11/11 further aligns him with his compatriot and confidant, Fischer, who several years later would also attain the only perfect score (also 11/11) in U.S. Championship history. Lombardy and Fischer both share the middle name "James" and both had the same early teacher, Jack Collins. The duo were also both good in their early years at fantastic offerings of the queen.

Just one year after Fischer's "Game of the Century," Lombardy won an even shorter miniature over the second place finisher in that world junior championship.

In 1960 Lombardy also helped the U.S. win the world student team championship, and won another individual gold in the process. Held in the Pioneers Palace in Saint Petersburg, Russian (then Leningrad, Soviet Union), Lombardy played every round and tallied 11 wins and two draws. That included a penultimate round win over future World Champion GM Boris Spassky.

For deep analysis of the game and more thoughts on Lombardy, check out GM Kevin Spraggett's blog.

IM Anthony Saidy, who told Chess.com that he first met Lombardy in 1950, reminded that the challenge that year was immense. The Soviets had won several world student team championships in a row, and "we were on their turf." Saidy played board four for the match with the Soviets and his draw helped give the U.S. a 2.5-1.5 match win.

To clinch the nation's first-ever world team championship of any kind, the U.S. still had to score at least a 2-2 tie against Bulgaria in the final round. Lombardy described what happened next in a "Chess Life" article from 1960:

"Although none of our players seemed nervous the tension was high. Thus it was with the greatest enthusiasm I received the news that the Bulgarian captain had offered a draw on all four boards! If we were to accept we would become world champions! After considering the offer approximately 15 seconds we became world champions."

In that same year of the historic upset, FIDE awarded Lombardy the GM title. According to then FIDE Vice President Jaroslav Šajtar, Lombardy's performance in Leningrad contributed to FIDE's bestowal of the title.

Also in 1960, he finished second place to Fischer in the U.S. Championship, but Lombardy declined the qualification to the 1961 Stockholm Interzonal.

Shortly after, Lombardy entered seminary. In 1967 he was ordained, and spent several years as a practicing priest in the Bronx. He remained an active chess player during this time, including winning two U.S. Open titles in the 1960s.

Later, he served as Fischer's closest chess companion during his countryman's successful 1972 World Championship Match, also against Spassky. He provided "important moral support" according to Saidy.

His son Raymond Lombardy told Chess.com that his father felt it was simply "unlucky" for this father to be the peer of Fischer, in the same way that many great tennis players that are Roger Federer's age might be swallowed by that shadow. Still, Raymond said his father was honored to be Fischer's most trusted chess sidekick.

"He was always very proud of what he and Fischer had shared over the years, Raymond said, "though I always had a sense that my father had come to the conclusion that he would have been that famous, top level player that Fischer turned out to be, had Fischer not been around."

Raymond said the favorite story his father told him from the match was when one evening Fischer scoffed at the idea of reviewing Lombardy's notes, and they instead went bowling for the night.

Eliot Hearst, who was Lombardy's teammate on the 1960 gold-medal winning team, wrote in 2010 in "Chess Life" that Lombardy and Spassky remained good friends even after all the over-the-board battles.

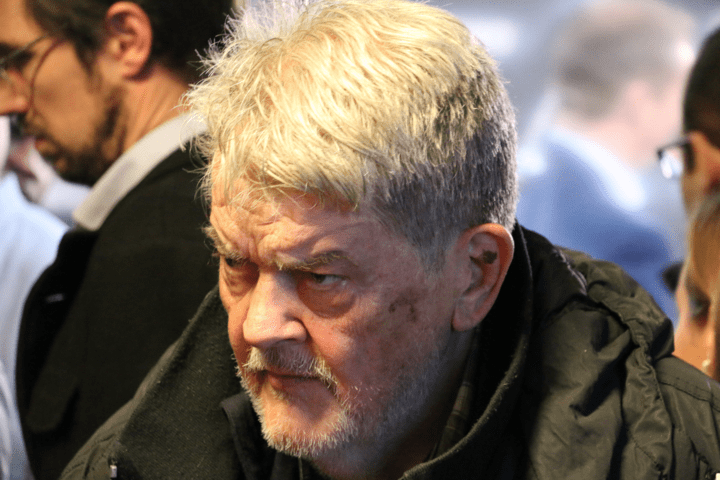

GM William Lombardy in an undated photo, courtesy of US Chess Federation.

In 1975, Lombardy won a third and final U.S. Open.

The 1976 Olympiad Team gold in Haifa, Israel, meant that Lombardy won three world championships in his career, counting the world juniors and world student teams.

"I liked him, and we were always on the best of terms," GM Jim Tarjan told Chess.com. Although they lived on opposite coasts and didn't see each other outside of tournaments, Tarjan said, "He was always very cordial and supportive of me and my chess."

IM Elliott Winslow played Lombardy in 1976 and said he frequently saw Lombardy in New York City on weekends. Winslow said Lombardy liked to kibitz backgammon games. Many people over the years could say the same about Lombardy's impromptu visits to the chess corner of Washington Square Park.

According to an article in the New York Times, Lombardy took care of Collins later in the 1970s. Then in 1984 Lombardy married Louise van Valen after meeting her at a tournament in Tilburg, Netherlands. They had a son, Raymond Lombardy. His wife and son moved to her native Netherlands less than a decade later.

Raymond, now a few days away from turning 33, told Chess.com that while he dabbled in chess, he never gravitated toward it. Instead, he regularly played the card game "Magic: The Gathering."

"I guess you could say that this is the genetic legacy my father left me, as I have always had the ability for strategic thinking and love to use my mind to break down puzzles and problems," Raymond wrote to Chess.com from his home in Dordrecht, Netherlands.

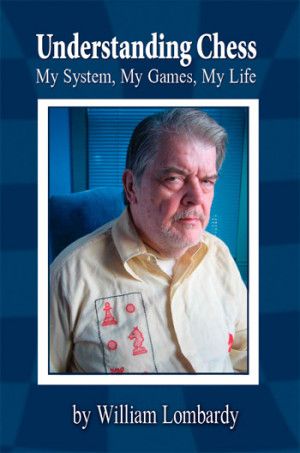

In 2011, Lombardy published an autobiography with more than 100 annotated games: "Understanding Chess: My System, My Games, My Life."

Lombardy's web site lists a planned book detailing the "truth" behind the movie "Pawn Sacrifice" (where he was played by Peter Sarsgaard), but that volume never came to print.

After being based on New York City for so long, Lombardy became itinerant in his final months of life. A protracted legal battle over rent payments resulted in him leaving his longtime apartment. Last year, he gave up the fight, and seemed to sense his own ending.

"My father was a kind and loving man," Raymond said. "Sadly, life had treated him in such a way that I feel he became somewhat bitter towards the end. This resulted in him rejecting more and more of his family members, with mutual stubbornness causing that damage to never be repaired in many cases."

"A man as old as I, you couldn't get closer to death," he told the New York Times about the impending eviction. Raymond echoed the thoughts of others in the chess community when he said his father was "too proud" to seek help from people that offered.

Eventually he did accept help. Lombardy moved to Chicago for a time before continuing on to California. Winslow said he'd been in the Bay Area for about one month before passing.

Saidy said their final meeting was dinner together in Santa Clara, California on September 23 of this year.

William "Bill" Lombardy at the Mechanics' Institute Chess Club in San Fransisco on September 24, 2017. Photo courtesy of Pia Fransson.

Raymond explained the relationship with his father at length, and it is fitting for him to close the chapter on his father's life:

"I only communicated with my father through the occasional letter or phone call up until 2008. That was the first time I visited him, being 24 at the time. Sadly, we had an argument that had great consequences for him and myself. The argument was severe enough, that I decided to stay with his brother Michael for the remainder of my time in New York, which in turn caused my father to sever all ties with his brother, to whom I assume he never spoke to again until Michael's death earlier this year. Years later, in 2014, I had decided that I did not want that fight to be the last memory of my father, so I took a leap and booked a ticket to New York to surprise him and introduce him to my girlfriend, who joined me on the trip. Even though we had not spoken at all since 2008, my surprise visit was welcomed by him as if nothing had ever happened. This, I believe characterizes him. He was a man who could hold a grudge, but if someone would take a step to reconcile, he would always accept the hand. This three-day visit was the last time I saw or spoke to my father. My own personal life and the everlasting transatlantic gap have been the main reasons for the lack of frequent communication, sadly. Though I am glad I took the step to visit him that one last time, since it was very pleasant and my last memories of my father are warm and loving."

Raymond told Chess.com that Lombardy is survived by him, sister Natalie Pekala, and nieces Samantha and Victoria Lombardy.

Chess.com sought several players' thoughts on Lombardy, and renowned author/teacher NM Bruce Pandolfini's response was so detailed and poignant, we are publishing it here in its entirety with limited editing.

-------------------------------------------------

While I didn’t know Bill as well as I would have liked, I always looked up to him and cherished any hopeful thing he ever said to me. I think I originally saw his name in Milton Hanauer’s outstanding primer, “Chess Made Simple.” If I recall properly, Dr. Hanauer used a pretty shot from one of Bill’s early games.

I first met Bill Lombardy for real, however, at the Marshall Chess Club, just after his match with Larry Evans [Ed: Evans narrowly beat Lombardy 5.5-4.5, just before Lombardy began studying to become a priest.]. I won’t lie and say we became fast friends, because that wouldn’t be true. At points, even though we weren’t adversaries, it almost seemed we were. Indeed, we had our disagreements. But we both loved chess and had our share of good conversations and friendly encounters through the years as well. Bill was a complex man, and like many public figures, he could seem glib and aloof, and that made him difficult to really know. In fact, the true Bill Lombardy, with a burning passion for ideas, noble and high, didn’t always come out on the surface.

As a player, I always thought Bill was classically influenced. He believed in principles, and he revered the great attacking players of the past, going back to Morphy and Anderssen. This was evident from how zealously he could talk about them. Yet on the other hand, Bill was very much a positional player. He routinely tried to avoid weaknesses and would steadily attempt to accumulate small advantages, striving to nurse home his edge in a solid endgame. In a way, he was pragmatic like so many American chess artists, taking a little bit of this and mixing it with a little bit of that. To be sure, at his height, it’s fair to say he was among the six best players in the country. [Ed: He was also opportunistic. Watch him here defend and then wiggle out of a bad position against GM Viktor Korchnoi, who was at the peak of his powers in 1979.]

Lombardy was an extraordinarily gifted person, one of the most all-around endowed chess players I ever met. He knew quite a bit about practically everything, and he was very opinionated, willing to share his thoughts with anyone in the vicinity. I believe he appreciated his friends, and he had many, but he often felt betrayed, and some of those who had helped him the most could soon fall into disfavor. You didn’t want to incur Bill Lombardy’s wrath either. Not only was he a larger-than-life chess king-pin, he had a razor-sharp wit and skilled command over the English language. Ex cathedra, he could trenchantly praise you and devastatingly damn you at the same time.

A couple of stories. As a teenager, I was playing in a Marshall Chess Club tournament. At a critical moment in a game against a 2300 player, I went into a deep think, while Bill stood right behind me for the entire 20 minutes or so. I can’t tell you how intimated I was, with a chess goliath putting me under the microscope. Somehow, I fought off my chagrin and found an ingenious resource that turned the game around. After playing the move, I got up to relieve the tension, when Bill whispered in my ear: “That was nice. I didn’t think you’d find it.” I didn’t know if I should smile or what. But coming from Bill, no matter what his real point was, I was elated.

On another occasion I was conversing with Bill at Jack Collins’ wonderful New Year’s Eve party, a festive get-together of chess people and characters that used to be celebrated every year at the home of Jack and Ethel Collins. Just before midnight, glass of wine in hand, Bill and I broke off our colloquy to observe a blitz game between a young male and a young female, both of whom were prodigiously capable. The game was remarkable, and the young female completely outplayed her opponent, forcing mate in an exciting time scramble. When it was over, amid the hoopla, Lombardy turned to me and sotto voce opined, in his typical double-edged way: “That’s no girl!” Of course, Bill’s politically incorrect, sexist remark was at the same time a huge compliment. That was his way of saying she’s really a tremendous player.

This past summer I visited Bill in the hospital a couple of afternoons. He certainly didn’t expect to see me the first time, and he was a bit guarded. To break the ice, I gave him two baseball cards, one of Joe Dimaggio, the other of Ted Williams. Just like that, he began to smile broadly and speak effusively. We then had a very enthusiastic, nostalgic chat. Bill recalled various happenings through the years, and we joked and laughed over chess personalities and events of the past. I could see how proud he was of his association with Bobby Fischer. Bill described how he had initially met Fischer, how he had helped him, and how impressed he was with Bobby from the outset. And yes, he was particularly pleased by having achieved an 11-0 score in the World Junior Championship, paralleling Bobby’s 11-0 result in the 1963-64 U.S. Chess Championship. For the chess fan in me, hearing it all first-hand, there was magic in those numbers. It was true gold.

And so I am saddened today. As I’ve indicated, Bill Lombardy and I weren’t always in harmony. But I admired him greatly. Who wouldn’t have? For me, he was a chess idol. And for the rest of the game’s fans, I hope he will always be recognized and treasured as an integral part of America’s chess efflorescence triggered by the ascendency of Bobby Fischer. Truly, chess has lost one of its giants.

--Bruce Pandolfini