Importance of Early Development of Visual-Spatial Intelligence

CHESS SOCCER CONNECTION

We have already made excursions to other domains before to find beautiful, unexpected connections that they have with chess. For example, we learned about the creative thought process of the photographer Ansel Adams that most closely resembles the chess player's way of thinking.

Today we are going on a field trip to soccer turf. This is another field where visual-spatial intelligence (VSI) is vitally required to perform well. VSI helps us "understand, remember and recall the spatial relations between objects, and orient ourselves in the world."

People who possess VSI are very good with directions. Here I not only mean reading maps. Mind also creates its own cognitive maps. These constitute simplified mental models that represent a shortcut to complex external reality; they bring understanding of our surroundings, and affect our abilities to reason, take the right course of action and solve problems. Without a high VSI to help us see the connections, there is no clear picture and right perception of reality.

Proper "reading" of the spatial, or better yet, structural and functional relationships between objects, or agents in a system (e.g. men on the board, or soccer field), enabled by VSI, is thus essential for how we act in the world.

It has to be noted that this ability and accompanying mental models develop very early in the learning process. This is the key mental faculty every beginner should start acquiring right from Square One, from Day One. This is the basics of every domain of human endeavor, getting a proper frame of mind made of big ideas and simple concepts, not learning particulars, rules, technicalities, petty trivialities that we typically teach in the very beginning.

Mental models not only start forming from Day One, they also normally get shaped, for the most part, very soon, finding its place in the unconscious brain. That way, they become a mental core to which all new concepts that we learn as extension to our prior knowledge, stick to. Later, when we act (say, making a decision about next move, or what to do with the ball), all habits we rely on and the mental procedures we internally execute always come from that deep-rooted, subconscious mind as the first thread of thought. It is in fact our basic mental engine for making decisions.

Sadly, by early teaching irrelevant details instead of ideas and concepts, the traditional teaching is not conducive to helping develop visual-spatial intelligence. Yet only mental models can help us make sense of our surroundings and be able to act successfully. This is something educators have been failing to notice. They keep teaching the mechanics first, totally oblivious of the existence and importance of mental models for which the basic piece relationships make the foundation.

In chess, they say, any plan is better than no plan. Likewise, any mental model is preferable to no model. Here lies the main reason why basic education in math, or chess is failing the beginner, lack of concepts and ideas early in the learning process. That is why we should focus on them from the very start when teaching and learning.

As Charlie Munger put it, "A good idea and the human mind act something like the sperm and the egg ― after the first good idea gets in, the door closes."

Now think what happens when a bad idea, or no idea at all, gets in? And it is pretty much what our basic education looks like.

* * *

Now back to soccer. And the first question that may come to mind is what in the world soccer has to do with chess? Soccer is another activity where agents play and compete in Space and Time, much more dynamic though. In chess, pieces move along trajectories that can be easily anticipated, one at a time. In soccer, twenty two players move, all in different directions and at different speeds. Yet we are going to see that the basic relationships soccer players make during the game come down to two and three-men connections. Exactly like we see happen in chess.

There is another thing soccer shares with chess. They also start with mechanics. We start with the moves, they start with how to hit the ball. In both cases the visual-spatial intelligence is neglected. But the thing is not how to kick the ball, or move a pawn. It is why and where the ball should be delivered based on the current network of interrelated participants on the field. In other words, the relationships they have got into and the structure they have formed. Visual-spatial intelligence can only give the power to understand situation and act meaningfully.

The material I used here is from Youth Soccer Drills written by the soccer coach Jim Garland.

Garland, a veteran physical education teacher and coach, has recognized the simple fact that young players can only understand what is going on during the game through spatial awareness.

The coach begins Chapter One with two drills that aim to foster visual-spatial intelligence from the very start,

"The development of spatial and movement concepts should be an integral part of beginning players' training. Often these concepts are neglected in favor of drills designed only for developing kicking, heading and other ball skills. This is unfortunate. A player who understands spatial and movement concepts moves with confidence."

"Spatial concepts are essential for tactical awareness, which helps a player decide where or when to move to support a teammate who has the ball. Understanding spatial concepts also allows a player in possession of the ball to make better tactical decisions concerning where and when to penetrate the defense using dribbling, passing, and shooting skills." (highlights are mine)

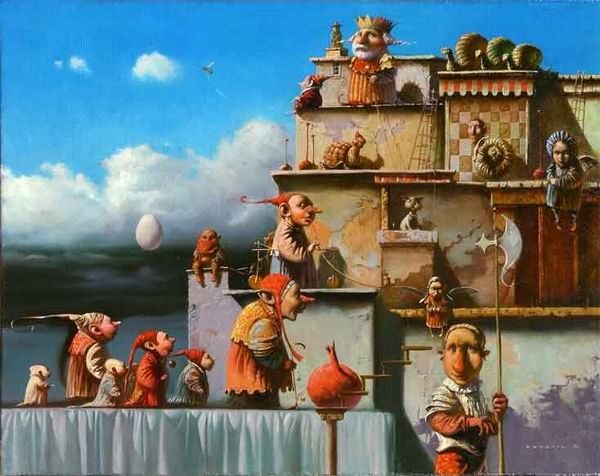

Note that it is, very importantly, spacing taught first, before movement or any other soccer skill (see also the book's front cover). Movement concepts follow on the space concepts and deal with how players negotiate space (the Belgrade teaching method I use when teaching complete beginners has the same approach, something GM Jonathan Tisdall is particularly fancy of: "very interesting to see the bit about learning to move the rook without being told.").

Garland's training in spatial concepts includes teaching of open space (space that is unoccupied by players), closed space (occupied by one or more players), personal space, general space, and vision (the entire field of vision a player must monitor, using scanning techniques).

Open space (drill #1) and Closed space (#2) build a base of knowledge about how to use space. The drills are using a ball and two game markers set about ten yards apart. One player stands by one of the markers and walks to the other marker (see figure). Then the same player dribbles the ball to the other marker. Finally, a teammate gets to stand by the other marker. The first player passes the ball to him.

The Closed space drill goes like this: Player A stands by one of the markers, while one opponent player (player B) stands on the line midway between the markers. The player A walks on the line to the other marker. Then, he dribbles the ball to the opposite marker without going off the line. Finally, teammate C stands by the unoccupied marker and player A passes the ball to player C. Of course, player A gets the idea that all these things are impossible to complete (in chess we call it blocking).

Those of you who are regular readers of the blog immediately recognize a striking similarity with the basic piece relations we discussed on this blog before. Garland's drills feature only two and three players. The elementary contacts in chess also establish between two chessmen (attack, restriction, protection) and three in case of pin. Look, for example, how drill #1 nicely illuminates the idea of how chessmen show huge activity along open lines, or how drill #2 above closely reminds of the body effect chess pieces produce.

Don't let these apparent simplicity of elementary connections made from two and three agents deceive you. All complexity and sophistication that can be seen in a complex system emerges from these basic interactions (note Garland's remark, "refer to these drills often when explaining the effective use of space in training and game situations").

Even though soccer is much more complex and dynamic than chess as mentioned before, both games ultimately rely on the elementary connections.

Ok, over and over again you see that I get back to relations as one of my favorite topics. Why? Because we as chess educators still don't see how important they are early in the learning process. When we teach by using the traditional method with the moves shown first, we hear only the single notes. The moves are not seen as parts of a coherent whole, a system. By neglecting structure and function, we make beginners miss the essence. Individual move perceptions should be visited by unifying chess ideas that only can bring the meaning. As we have seen in the complex system post, the moves are just a chessman's property unable to explain the meaning and nature of chess as a structural and functional whole.

"History offers a ridiculous spectacle of a fragment expounding the whole." ―Will Durant

Hey chess educators, still not convinced that relationships is the first concept and should be taught first?

If that is still the case, no problem. Next time, I am going to give more examples from even more domains beyond soccer...