Lines of Operation: A Framework for Strategy Design in Chess, Warfare, Sport Contests

DETERMINING AND MANAGING LINES OF OPERATION SHOULD BE YOUR STRONG SUIT IN WAGING CHESS WARS.

The lines of operation are essential to the conduct of strategy. For on the good or bad choice thereof the final outcome of (chess) war mainly depends. If it's ill chosen, all your achievements in a game, however brilliant, will, in the end, be found useless.

The above is equally true for both warfare and chess that was invented as a simulation of war. Here is Vladimir Vukovic in the 'Art of Attack in Chess' classic:

"Attack [takes place] along the ranks, files and diagonals. The line concerned has to be 'captured,' i.e. is one's own long-range piece has to be placed on it, confrontation by the opponent's corresponding piece has to be overcome, and the line has to be 'cleared' of all enemy influence. Outposts lie on such lines; batteries and pins take place along them. In a mating attack the line may finally witness the execution, i.e. checkmate."

Compare what Carl von Clausewitz had to say about the lines of communication: "Supplies of every kind, convoys of munitions, detachments moving backwards and forwards, posts, depôts, reserves of stores, all these objects are constantly making use of these roads, and the total value of these services is of the utmost importance to the army."

According to Napoleon's General, Baron Antoine-Henri Jomini, a line of operations consists of a base of operations, lines of communication, an army with a front of operations (where the contact with enemy is likely), lines of maneuver, and objective points. The concept of line of operations may be misunderstood and poorly defined. Yet, it remains an enduring concept of great importance towards art of conducting (chess) warfare.

Now Major Charles W. Coxwell, School of Advanced Military Studies: "Understanding the elements of line of operations provides a basis from which to explore its application. A commander applies the concept of line of operations to orient his force on operational objectives; he uses the concept to move and sustain a concentration of force (logistics), and posture the force in a position of advantage (maneuver) to achieve his objectives through decisive combat operations. The commander generally directs these operations against the enemy's Center of Gravity."

[the Center of Gravity? yes, we learned about it in Physics class back in school. But what in the world is that in chess? The CoG, in short, is a warfare concept from von Clausewitz, the "most important feature of the position" as Vladimir Vukovic put it. It is one single factor that stands out among many elements of the current situation; it is what matters most; it is what the Great Generals of battlefield, or Grandmasters of chess battlefields are able to spot in a moment to orient their thinking and actions. ― I am posting four articles on CoG in near future, so stay tuned!]

Today I am going to share a guest post on the lines of communications that I wrote as a freshman blogger for NM William Stewart's OnlineChessLessons.net (now iChess.net) that was published on Sep 22, 2012 (its Spanish version was posted the other day).

Avenues of Attack: Cut Them Open or Cut Them Off?

The secret of war lies in the communications. –Napoleon Bonaparte

In a combat situation when lives are on the line, the lines of communications may mean life or death.

Open and secure lines of communication are vital for any (military, chess, sports team) force to operate effectively. Think football for example, without being able to pass the ball to the forward, or wide receiver, your game sucks.

What avenues of attack to choose?

.

The same is true in chess. Communication lines allow your troops to extend their operational range and mobility in order to fight successfully the opponent. The lines are routes that also connect your fighting units operating deep in the enemy territory with their “supply base” from where reinforcements are transferred along these routes to strengthen the grip on the enemy.

Both line opening and line closing are a natural consequence of each move you make on the chessboard. The line opening is the result of a piece leaving a square. The closing is a consequence of occupying another square with the same piece.

There are useful and harmful sides of this effect. Increased mobility and scope of action are normally associated with line opening. Line closing has a reverse effect restricting fighting potential of chessmen.

While line opening is a well recognized topic and is given due attention in chess literature, line closing is kind of neglected a little. That is why I wanted us to cover it today.

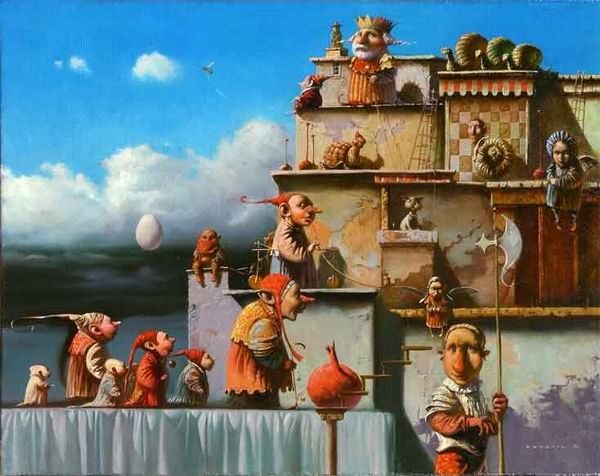

This guy simply doesn't get what we are talking about here - it simply defies comm lines laws, while being watched by the rest of its army open-mouthed (chess cartoon by Jovan Prokopljević, Serbia)

.

It follows from what is already said, that you may benefit from a line closing maneuver if it eventually restricts the activity and mobility of the enemy pieces without interfering with the freedom of your men (understandably, this may sometimes be a conflicting task).

There are two ways you can use line closing effectively:

1) You play a piece that obstructs a mobile enemy piece,

2) You force the opponent to make a move which closes the operating line of his own piece.

On top of this, sometimes you also want to:

3) Spare a hostile piece (by not taking it out) if it has a harmful effect to its own camp, and

4) Block such a piece on its square to prevent the opponent from freeing up himself (by opening lines).

The justification for #3-4 above is that any encircled or blocked enemy units, in warfare in general, want to recover and attempt to break out and regain contact with their main force. As always, you must plan for the enemy’s most probable reactions (which is just a part of your overall strategic handling, ever watchful for enemy intentions).

.

Henri Gerard Marie Weenink, born 1892, was both a problem composer and player.

In the 1931 Amsterdam tournament he came in 1st in a field that included Max Euwe and Rudolf Spielmann.

.

So how can Black stop the pawn, a careerist, after an obvious

1.a7

Well, the White’s king is controlling the Rook's entry points on the a-file, so it seems Black must use the g-file to transfer his Rook to the back rank.

Yet, if he tries it immediately, it won’t help: 1…Rg8 2.Bg3+! and if the King moves, then 3.Bb8 with queening. Here we see an instance of line closing, actually an example of #1 above.

But Black can put up a more stubborn resistance.

1…Rg2+

The king must stay away of the 3rd rank as after 2.Kb3 follows 2…Rg8, and 3.Bg3+ won’t work now – the bishop is taken out with check, 3…Rxg3+.

The White’s Monarch is to keep control of the entry points on the a-file (a1, a2). Looks like a perpetual?

Not really as White has a clever trick up his sleeve!

2.Kb1! Rg1+

.

Now what?

3.Be1!!

Line closing again! Black must accept the sacrifice as another try with 3…Rg8 isn’t working again, 4.Bg3+

3…Rxe1

Now we see the main point of the sacrifice: the rook is driven on the e-file. Incidentally, the Black’s ruler is there too, so we see the harmful effect (mentioned above) that a friendly piece may have on its army effectiveness. It’s kind of self-restriction, or self-interference (#2 above).

Now, it’s few more checks left and it’s all over:

4.Kb2 Re2+ 5.Kb3 Re3+ 6.Kb4

Of course, not 6.Ka4? Re1! and Ra1

6…Re4+ 7.Rb5 and wins.

Now, master line handling on the battlefield and your game will sure pick up!

.

.