Winner's POV Chapter 5: New York 1857

In Winner's POV, we take a look at tournaments from the 19th century and see the games that allowed the top player to prevail. Some tournaments will be known and famous, others will be more obscure - in a time period where competition is scarce, I believe there is some value in digging for hidden gems in the form of smaller, less known events.

Chapter 5: The First American Chess Congress

While England did its part in kickstarting international competition across Europe, the chess scene to the west was sorely lacking. America had no shortage of chess clubs, however in terms of competition, the scene was barren. The last major event in US chess would have likely been back in 1845, where the first US Chess Championship match was played between Charles Henry Stanley and Eugene Rousseau. Ever since then, America had been rather silent.

There were some interesting occurrences between 1845 and 1857, however. The arrival of Johann Jacob Löwenthal and his subsequent tour in 1850 garnered a decent amount of interest in chess, culminating in Löwenthal opening his own chess parlour (and later traveling to London for the 1851 tournament). Following the London 1851 tournament, Stanley attempted to replicate Howard Staunton's work by preparing a chess tournament for the 1853 New York World Fair (as Staunton had organized the London 1851 tournament to coincide with the Crystal Palace Exhibition), however nothing came of it.

As the London 1851 tournament book became more widespread across America, the interest for a chess tournament gradually grew. Primarily led by the New York Chess Club, the American clubs and masters began organizing in early 1857, and that October saw the first edition of the American Chess Congress.

Format and Prizes

16 players took part in this knockout event, which used a first-to-three match system, except for the grand finals which was first-to-five. There were prizes for the top four, so the semifinals losers were allowed to play one more match. Of course, we aren't exactly concerned with them, now are we?

The tournament book once again has a simple record of the prizes awarded, in the accounting section:

$300 in 1857 is apparently worth $10,218 today. There was a $10 entry fee for all players, so winning any prize resulted in a tidy profit.

Players

The players were presented in a nicer manner than in the London 1851 book, but only partially:

These 12 gentlemen were the ones who initially put their names forward. They were then joined by William James Appleton Fuller, Hardman Philips Montgomery, Daniel Willard Fiske (the tournament book author), and Samuel Robert Calthrop.

Using the 1856 Edochess list, the strongest players present were Paul Morphy (1st), and let's be honest, who else matters? Morphy had occupied the #1 spot on the Edo ranks all the way back in 1848, and would continue to hold that spot until the mid 1860s. The reason this tournament is so well-known is not because of the strong field, but more for being the only tournament in which Morphy played.

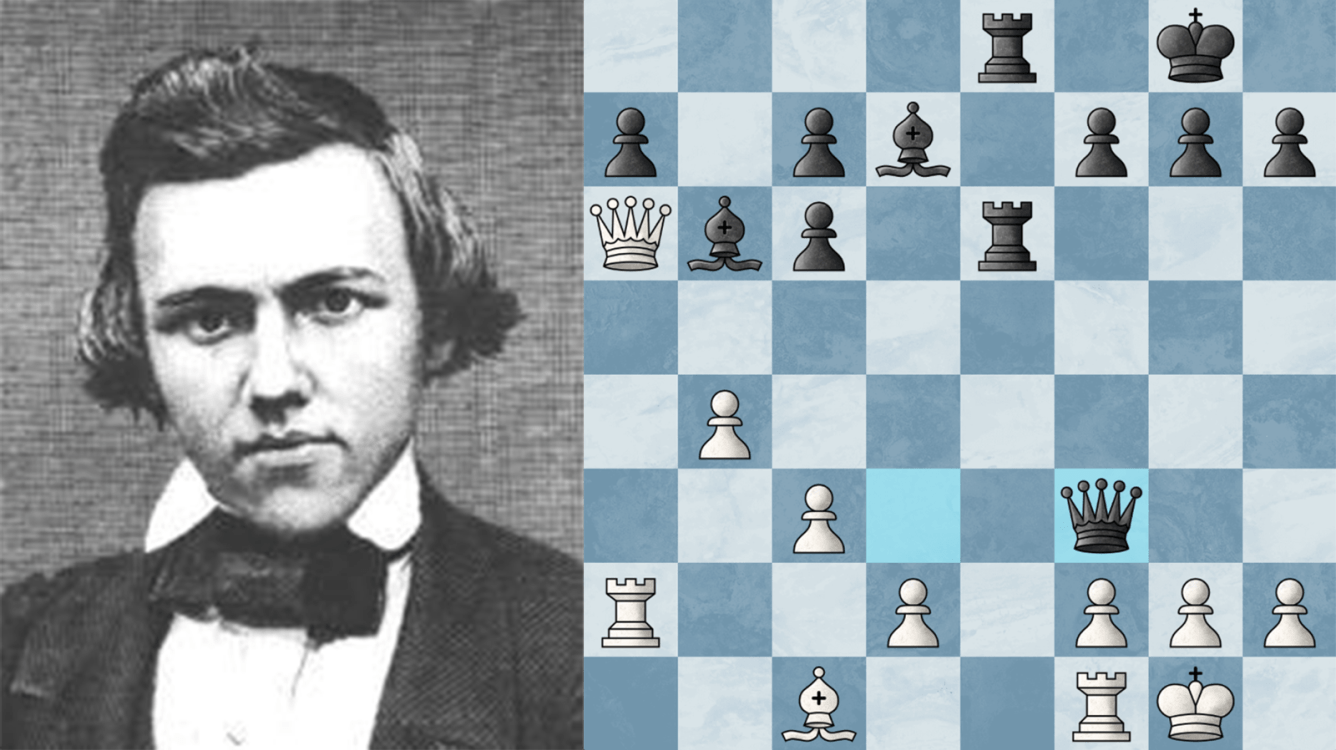

The Winner: Paul Morphy

If this is your first introduction to Paul Morphy, then you are in for a treat. Morphy was so far ahead of everyone else in the world back in the 1850s, his dominance was comparable to that of Bobby Fischer in the early 1970s. For those of you who have seen Morphy and his games before, I hope you enjoy this walk down memory lane, looking at the earliest games from Morphy's "career" in competitive chess. With that, it's time to look at the New York 1857 tournament from the Winner's POV.

Round 1: vs. James Thompson

James Thompson was the President of the host New York Chess Club, and the winner of their 1855 tournament (which featured a few of the players present in this tournament, Thompson personally beating Frederic Perrin and Napoleon Marache). He was ranked 50th in 1856, and likely one of the stronger players present at this event. How did he stack up against Morphy, however?

Thompson tried the safe Giuoco Pianissimo for the first game, using the setup popularized by Stanley (Nc3-e2-g3). Morphy, wanting to take advantage of Thompson's uncastled King, quickly sacrificed a pawn for a powerful central force. The plan must have surprised Thompson, who initially retreated before being blown out of the water. Given that few people present had personally seen Morphy's play before this, they received a very spectacular first display.

As their first game only took an hour to play, the two engaged in their second game later in the same day. Thompson went for a Sicilian, where his early d5 thrust was quickly refuted by Morphy, who won a pawn. While Morphy looked to trade pieces and play the endgame, Thompson found active play, and for a while, put pressure on Morphy.

The problem was, Morphy's extra pawn was a passed d-pawn, which Thompson gradually failed to properly play against. He ended up dropping a second pawn, at which point Morphy never relinquished control on his way to conversion.

Thompson took the following day off, so the third game was played on the third day of the Congress. Another Giuoco Pianissimo was played, though Thompson took much longer to develop his Queen's Knight, instead castling much quicker. Morphy's play was as principled as a modern player's, and by virtue of Thompson dropping his f2 pawn, he soon had a clearly better position in almost every way.

The battle ended up being resolved on the Queenside, where Morphy's more active King aided him in winning a second pawn before Queening it with a nice zugzwang. Shutting out the New York Chess Club's President in the first round is among the strongest statements one could hope to make, and Morphy did just that.

For context, Morphy won his third game on October 8th, which meant he would have a long time to wait before the second round; Stanley, who was suffering from illness, played his first game on the 9th. Among Morphy's activities during this waiting period included a double blindfold game against Louis Paulsen, who was giving a four-board blindfold exhibition (Morphy would be the only person to beat Paulsen in that exhibition). It wasn't until October 14th that Morphy's next opponent would be decided, and the 15th is when they finally began.

Round 2: vs. The Honourable Judge Alexander Beaufort Meek

I didn't realize how much bigger this picture is than the others, oops.

Morphy had graduated from law school earlier in 1857 (and was playing in this tournament to pass the time until he was old enough to legally practice), and Judge Meek was coincidentally among the only people to know of Morphy before this congress. The pair had played 5 recorded games outside of this congress, with the score being 5-0 in favour of Morphy. Edo has Meek ranked 166th in 1856, and he defeated William Fuller 3-2 in the first round.

Meek got into a bad position in a Ruy Lopez, as he tried to set up an f2-f4 thrust that never happened. He tried to sacrifice a pawn to keep up with Morphy's pieces, but it never amounted to anything. With Morphy having cleverly opened the a-file, his Rook was able to join his Queen and Bishop in tearing apart Meek's paper-thin defenses.

Meek went for a similar French Defense as Staunton tried in his match against Anderssen, one-upping the Englishman by fianchettoing both Bishops. However, he quickly closed the center and shut both of them out, allowing Morphy to demonstrate his superior positional understanding. He thrust forward with g2-g4, sacrificed a Knight on g6 to bust open the Black King, and went on to checkmate Meek with a vicious attack.

With his back against the wall, Meek broke out his secret weapon: the Göring Gambit. While Morphy could have defended normally and been alright, he decided to make a statement with a defensive exchange sacrifice that stopped Meek's attack outright. Shortly after, Meek's own position became shaky, and Morphy claimed his sixth consecutive win without any issue.

This game ended on October 17th; it wouldn't be until the 22nd that his semifinal opponent would be decided.

Round 3: vs. Theodore Lichtenhein

As of 1857, Theodore Lichtenhein was considered to be the "champion" of the New York Chess Club, and had thus far carried himself well. He had closely defeated Stanley in round one 3-2, before trouncing Frederic Perrin 3-0 in the second. Edo does not have a ranking for him in 1856, but his performance at this 1857 Congress put him at 13th for that year, ahead of previous Winner's POV subject Samuel Boden.

Lichtenhein went on the attack with either a Scotch Gambit or a Giuoco Piano (sources disagree on the move order) however Morphy made no attempt to keep the gambit pawn. This game featured one of the earliest, most prominent examples of zwischenzug in 10... Qh4! The Queen was excellently placed there, as Morphy was able to open up the center, rush the Queen back to d8, and checkmate Lichtenhein's uncastled King without issue. A splash of cold water for the New York champion, I must imagine.

Against Lichtenhein's Petrov Defense, Morphy essayed the Urusov Gambit, though Lichtenhein immediately returned the gambit pawn as well. This time it was Morphy who took his time castling, though it was meant to support his Kingside pawn storm that flew towards Lichtenhein's King. The attack was fierce, and despite there being chances to stop it, Lichtenhein missed both crucial moments (which involved the exact same move, funny enough). Morphy was looking impossible to stop.

For the first time in this event, Morphy had to face 1. d4, and chose to go into the Queen's Gambit Declined. Despite winning a pawn in the middlegame, Morphy's c-pawns were doubled and isolated, and Lichtenhein secured a Bishop on c6 that represented adequate compensation. Not wanting to push his luck, Lichtenhein coerced Morphy to liquidate, steering the game towards a drawn Rook and pawn endgame. Morphy's winning streak was over, but he hadn't yet been beaten, at least.

The rules surrounding drawn games would take some time to be standardized; players could switch colours after draws (like they did at London), or they could repeat the colours, as was the case here.

Morphy attempted to make the contest more exciting than the last by employing the Dutch, but Lichtenhein immediately started trading away every piece possible. By move 26, the players were down to just a minor piece each. Morphy, always looking for the win, sacrificed his Bishop for two of Lichtenhein's Queenside pawns, gaining a majority and apparently pushing it to victory. We don't have the moves past a certain point (and the engine evaluates it as even at that point), so there's no way to tell exactly what happened, other than Morphy had officially made it to the final round.

Lichtenhein would go on to win third prize, dispatching Dr. Benjamin Raphael 3-0 in the third place match. All things considered, it was a very good showing for New York's finest.

Round 4: vs. Louis Paulsen

Unlike the London 1851 tournament, the finals of this event doubtlessly featured the two strongest players. Paulsen's record up to this point was eerily similar to Morphy's: 3-0 vs. Calthrop in round one, 2-0 vs. Montgomery in round two (Montgomery had to withdraw due to work duties), and 2.5-0.5 vs. Raphael in round three (Raphael resigned after losing two games, for reasons unknown). Paulsen had also been showing off his blindfold skills, scoring 2.5/4 in his initial four-board exhibition, before topping himself with 4.5/5 in a record-setting five-board exhibition (albeit against much weaker opposition). The amount of build-up and hype released by the publishers at the time was tremendous.

Worth noting is that Paulsen did not have an Edo ranking in 1856, like Lichtenhein. As for 1857...

The final was sure to be a good one. As a reminder, this match would be first to five wins.

Paulsen began with the Sicilian line that bears his name, the Paulsen-Basman defense. He immediately ran into issues when Morphy planted a Bishop on d6 (a hole he'd have issues filling through the match) and had to deal with a cramped position. His plans to escape never went anywhere, and Morphy smoothly won a piece before checkmating. As in the previous three rounds, Morphy's first game was once again a blowout.

The second game was interesting for a myriad of reasons, both due to the moves played and otherwise. For starters, this game was one of the earliest examples of an early a6 in the Spanish (not exactly the Morphy defense, yet) and featured the classic Exchange Spanish battle of White's pawn structure vs. Black's Bishop pair. Morphy, being the activity expert that he was, utilized the Bishop pair marvelously.

The next interesting moment came shortly after Morphy sacrificed his Rook on g2, opening up Paulsen's King to a brutal attack. The quick Morphy apparently played too quickly, mixing up the move order of his brilliant combination by prematurely touching his Queen and being forced to move it. This slip allowed Paulsen to return some material to halt the attack, and enjoy the advantage of an exchange in the resulting position.

The last point of interest, existing outside the moves made on the board, was time. Paulsen contrasted Morphy completely, being among the slowest players of the entire field (I suspect that was partly why Raphael resigned their match; one of their games lasted 14 hours!). In the latter half of this game, I append the length of time Paulsen thought for each move, so you can see just how long he spent thinking. The game lasted 15 hours total across three days, with Paulsen never finding a way to make progress and agreeing to a draw. What a marathon.

Paulsen's next opening idea was the Two Knights, and the players repeated the line they played in the double blindfold game earlier in the Congress. Morphy, doubtlessly annoyed by Paulsen's slow play and his own hasty play, went for cheap checkmate threats that Paulsen easily dodged. While his position deteriorated, Morphy still had to contend with Paulsen's glacially slow play, which extended the relatively short game to 11 hours. The need for a time control was greatly demonstrated (there wasn't one formally in place for this event).

Morphy was no doubt looking to play a palate cleanser after suffering his first loss of the event, which explains his relatively safe play here. After Morphy won one of Paulsen's pawns, the players began exchanging pieces like Morphy did against Thompson back in round one. Unlike Thompson, however, Paulsen's defense was immaculate, and he set enough traps to prevent Morphy from gaining a winning endgame. Despite Morphy being up two pawns in the final position, it was one that was certainly possible to draw, and Morphy indeed agreed to a draw instead of trying to grind it out against his sloth opponent.

Morphy's usual strategy of planting a piece on d6 seemed to backfire in this opening, as Paulsen didn't mind losing castling rights in exchange for easy development and an excuse to start pushing Kingside pawns. However, Paulsen was defensive to a fault, and especially against an attacker like Morphy, he didn't seem to have much faith in his own attack. Once Morphy managed to trade Queens, the resulting position seemed quite pleasant for him.

Morphy chose to push this time, and Paulsen nearly calculated everything nicely, however he placed his King on the wrong square and dropped an important Queenside pawn. Morphy's confidence and accuracy grew, and before long he won a second pawn as well as connected passers. The Rook sacrifice at the end was the cherry on top, marking Morphy's second win across the first five games.

If you've seen any game of Morphy's from the American Chess Congress, odds are good it was this game. Morphy's play, both leading up to and including the most noteworthy move, were incredible. I think it'd be best if you just looked at the game for yourself.

Paulsen would later claim to be suffering from an illness during the second half of this match, and it would certainly explain his poor play. He went for a poisoned pawn in this opening, losing his Queen in the process. Morphy stuck another Knight on d6, placed a Rook on the open g-file, and (albeit not with squeaky clean technique) convincingly won the game. Three wins in a row for Morphy, one more would clinch the tournament.

The final game was a sadly anticlimactic affair, with Paulsen playing horridly out of the opening. First he dropped a pawn, then a full exchange, and Morphy wasted no time throwing his Queenside pawns down the board to victory. The final result was likely never in question, but this definitely isn't the last game you want to play in the tournament if you're Paulsen, I imagine.

Conclusion

By virtue of winning this tournament, and separately by the games he contested with Stanley, Morphy was declared the new US Chess Champion. He turned down the $300 prize, instead receiving a silver pitcher, four goblets and a salver (a type of formal tray) with his name inscribed into it. He also presented Paulsen with a medal - purchased by members of the Congress after witnessing his amazing displays of blindfold chess - which allowed the pair to part on more amicable terms.

As most of you know, Morphy would go on to tour Europe, playing the very best in the world at our royal game. However, as he would never play in another tournament, our coverage of Morphy must sadly end here. Getting to see Morphy's games at all, however, is a blessing in my book.