Winner's POV Chapter 9: London 1862

In Winner's POV, we take a look at tournaments from the 19th century and see the games that allowed the top player to prevail. Some tournaments will be known and famous, others will be more obscure - in a time period where competition is scarce, I believe there is some value in digging for hidden gems in the form of smaller, less known events.

Chapter 9: London 1862

4 of the last 5 tournaments we looked at in this series took place during a transition phase for European Chess, in which chess players and fans (primarily British ones) worked towards hosting chess tournaments with greater regularity and prestige. As mentioned in previous chapters, it was a little hard to coordinate everything needed for such an event, unless you have the luxury of a World Fair like during London 1851. While the following World Fair (New York 1853) would produce no events, London held the third World Fair across 1862, and would once again pounce on the opportunity.

The 1862 International Exhibition once again made international travel easier, and with many years of tournament planning under their belt, the British Chess Association took up the challenge of hosting another chess congress. With ambitions as large as those from 1851, but with the know-how to do it, this event was a major success.

Our prime focus will be on the grand tournament, but to mention a few other events:

- A handicap tournament (the subject of the next chapter, probably)

- A problem competition, in which anonymous puzzle composers submitted packages of puzzles to be judged under various criteria (further separated into "ordinary problems," "suicidal problems," and "studies/endgames."

- Blindfold simultaneous exhibitions given by both Louis Paulsen and Joseph Henry Blackburne.

In addition to various set matches and other chess-related activities, the congress was a success that I cannot properly illustrate through words. What I can do, however, is talk about the main event, and so I shall.

Format and Prizes

For the first time in this saga, we will be looking at a classic round robin (or "all-play-all" event). Each player was to meet with each other player and play a game with them - colours were randomized before each game, as far as I know. However, drawn games were to be replayed, the lone artifact remaining from the previous knockout format.

Unlike some previous events, the prize fund was written explicitly in the prospectus, allowing us to skip diving into the accounting section and instead pull up a straightforward picture:

£100 in 1862 is apparently worth £13515 in 2022. These prizes are smaller than the prizes for the London 1851 tournament (top prize was £183), however it probably makes sense given how many other events were taking place at this congress.

Players

As usual, let's start by looking at what the book, wrote, which is again sadly spread across two pages:

Of the players listed, Sergius Ourousoff and Jules Arnous de Riviere did not take part in the tournament at all, while Johann Löwenthal initially entered but withdrew after playing four games due to exhaustion (having taken a leadership position within the British Chess Association, he was mostly in charge of running the tournament, and didn't let his pride get in the way of his health unlike Howard Staunton in 1851). The remaining players were all present and will be introduced as this installment continues.

Using the 1861 list from Edo, the strongest players present were Paulsen (2nd), Adolf Anderssen (5th), Serafino Dubois (7th), Löwenthal (10th) and Wilhelm Steinitz (18th). Not only do we have a rather strong field, but an all-play-all means that there will be no early exits from the strongest competitors (as we saw in the previous chapter at Bristol).

The Winner: Adolf Anderssen

Anderssen was well known as a tournament specialist back when international tournaments were just starting, and the first two London tournaments were among his biggest achievements. We have a long event to go through, with many new people to introduce, so let us look at the London 1862 tournament from the Winner's POV.

Round 1: vs. Thomas Wilson Barnes

I'll admit now that, for a lot of the games, I don't actually know the dates they were played, or the order they were played in. This game is one of the exceptions, as I know it was played first. Play was set to begin on the Monday of the week, however Mr. Barnes was very gung ho and played his first game on the Saturday before, winning against Augustus Mongredien.

The style of annotation is vastly different than in previous tournament books (TBs), as Löwenthal placed a very high priority on the opening. To demonstrate this, he appended five variations to Black's 6th move, and would do so for many of the early rounds. The opening itself was a Petroff that saw Anderssen give himself an isolated Queen's pawn, which objectively neutralized any advantage but allowed for his usual attacking play.

It became very quickly apparent that Barnes - who had the most wins against Paul Morphy while the American legend was in Europe (8 wins) - was not on Anderssen's level. After saddling himself with Kingside weaknesses and trading off the best defender of them, he fell into a tactic that lost his Queen, quickly after giving Anderssen the win. A terrific start for Anderssen, who was widely considered to be the pre-tournament favourite.

Round 2: vs. Wilhelm Steinitz

Prior to his World Champion phase, Steinitz was your usual romantic player, with this being his international tournament debut. As mentioned in one of the above screenshots, he won the Vienna Championship in 1861, earning him the nickname "The Austrian Morphy." How would he fare in a field with many people Morphy defeated, however?

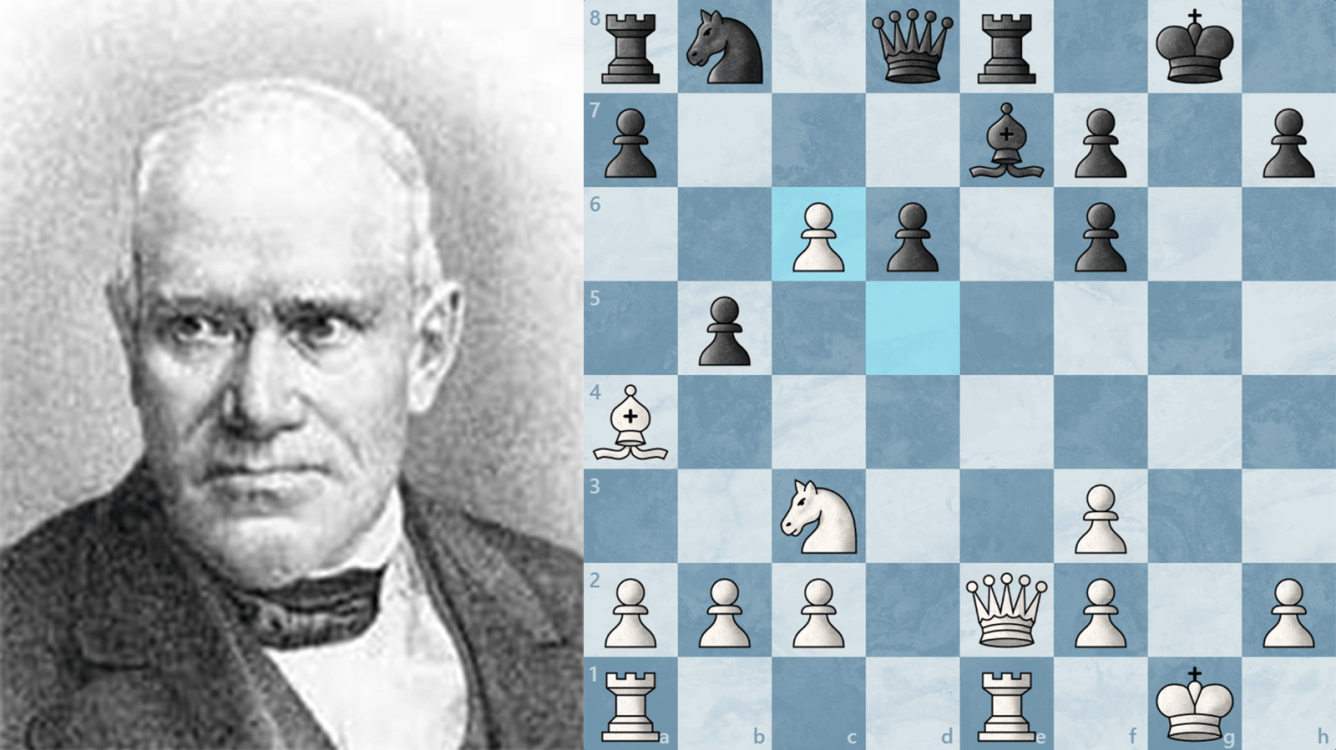

The Ruy Lopez was given three lines by Löwenthal on move 4 (and given how much theory exists today, this isn't a huge surprise), and Anderssen showcased why it was arguably the best opening at the time. He concentrated his attention on Steinitz's e7 Bishop, which was stuck and needed constant defending. When Steinitz tried to play on the Queenside, Anderssen uncorked a temporary piece sacrifice (which is seen in the thumbnail of this article) that shattered Steinitz's Queenside pawn structure and added another attacker to e7. Anderssen's game looked won before move 20.

What's interesting is that, as soon as Anderssen actually won his prize on e7, Steinitz found the defensive resource 21... Rb5!, which posed many problems for Anderssen. Once the piece was returned, Steinitz connected Rooks and stabilized the position, constructing a very drawable endgame. Still, Anderssen had most of the winning chances, so he played on.

The annotators didn't approve of Steinitz offering a Queen trade, though that wasn't yet the losing move. Anderssen later coerced a pair of Rooks off the board, but the draw was still in sight. It wasn't until Steinitz's 35... Rc5, incorrectly going after Anderssen's f-pawn, that the game was lost. Once Anderssen gained his passed pawn, he was able to shut Steinitz's Rook out of the game, and the rest was easy. An incredible game, and a good start to Steinitz's international career, despite the result.

Round 3: vs. Frederick Deacon

The last time these two played was at the London Club tournament of 1851, where Anderssen won from the Black side of a Bird's opening. In that game, Deacon attempted to play a similar structure as Marmaduke Wyvill when he beat Anderssen in game 6 of their London 1851 match (see here) but Anderssen was more than capable of adapting. 11 years later, did the British amateur learn anything new?

The Vienna was the newest addition to top-level openings, having received a lot of attention from German opening experts. Despite Löwenthal giving it a lengthy analysis, the players transposed into a Four Knights Italian instead of anything too spicy.

Deacon looked to go after Anderssen's King, and Anderssen correctly responded by playing in the center. Anderssen quickly proved to be the better player once again, stifling Deacon's attack and pushing his own agenda. Deacon struggled to come up with a way forward, and his indecision allowed Anderssen to advance and dominate the board. A decisive victory for the German.

Round 4: vs. James Robey

Though there were many strong players, there were also some whose names I don't know, Robey's being one of them. I know that he came all the way from Australia to play, but his accomplishments outside of this tournament are unknown to me.

Anderssen improved upon Steinitz's Ruy Lopez, and both pairs of center pawns were traded, leading to a tensionless and wide-open position. Anderssen wanted to save his Bishop pair in such a position, however his retreat quickly allowed Robey to expand. The Australian was precise, and quickly planted two of his major pieces on the 7th rank. For the first time in this event, Anderssen was in serious trouble.

The German master, always tenacious, found a defensive resource that Robey missed, and suddenly things were quite complicated. Robey decided to trade his Rooks for Anderssen's Queen, considered by some to be The Most Controversial Trade. Anderssen, once again, understood the position better than his opponent, connecting Rooks and nullifying any advantage that once existed. Once Robey snapped up the pawn on a7 (which always seems to be the start of some brilliant attack), Anderssen pounced, checkmating his opponent with a cute Rook sacrifice. It could certainly have gone worse, but thankfully for Anderssen, the perfect score remained.

Round 5: vs. Valentine Green

Valentine Green's reputation was that he was among the stronger British amateurs, though records of notable games are, as usual, scarce at best. I know of his name coming up again in future events, though his significance is still undecided.

Thankfully, this game was quite quick. Anderssen unleashed a King's Gambit, and while the players followed the theory of the time, Green's novelty was a poor one. The trades he initiated benefitted only Anderssen, whose pawns quickly rushed up the board to antagonize the Black King. Even after castling, Anderssen's pieces were well-placed to greet the monarch, and the shortest game of the tournament so far was concluded. Leave it to Anderssen to play the King's Gambit multiple times in tournaments and never get punished (recall his draw against Lionel Kieseritsky from London 1851).

Since this isn't a knockout tournament, I think it's important to provide status updates as we move along, as there's more to talk about than "half the field has been eliminated." Here's the book's report on the situation after the first week:

To provide further context: I'm using "Round X" a little loosely, since rounds weren't really a thing for this tournament. Players were free to encounter each other whenever they wished, though there was a deadline by which all games had to be played. I'll provide a crosstable at the very end of the article to give a full-picture summary of what happened, however we're less than halfway there, so let's first look at games from the second week.

Round 6: vs. Augustus Mongredien

Mongredien was the president of the London Chess Club, which took up more of his time than did playing. He played a match against Morphy in 1859, scoring only 0.5/8. Still, he was a notable amateur who had a fondness for testing irregular openings, which brought him somewhat positive results.

This game, however, was another good old King's Gambit. Anderssen played an early Bc5, which often allows White to play d4 without worry (as Daniel Harrwitz did against Anderssen himself early in Anderssen's career, see here). Mongredien indeed did just that, and soon he had an impressive center, made all the more useful when Anderssen committed to not castling. It wasn't without its chaos, but Mongredien was definitely better.

Soon Anderssen parted ways with a pawn, but it gave his King's Rook some much-needed play, which almost immediately proved relevant. The Rook planted itself firmly on f4, and together with the Queen, they made Mongredien's position extremely difficult to advance. Mongredien tried to play for a little bit, but he soon accepted the draw when it was made clear that none of Anderssen's pieces were moving. Still, being the first person to not lose against Anderssen was something of an accomplishment of its own at this point.

Round 6, Game 2

As mentioned earlier, drawn games were to be replayed until there was a decisive result. They were very big on the "drawn games don't count" rule(s) back then, and early all-play-all tournaments had various ways of mitigating draws. This was probably the most unsustainable, but it quickly fell out of fashion, somewhat.

Mongredien employed one of his famous double fianchetto openings, which was certainly dubious but allowed for traps to be set - one of which Anderssen fell into, crazily enough. His 11. Ng5 was swiftly punished, and he was forced to sacrifice an exchange early on in order to avoid playing a completely hopeless game. Mongredien traded off a couple more bits of material, leaving Anderssen with a gross position, both in formation and material. He was actually in a very losing spot!

Mongredien wanted more than to win through material advantage, and so he sacrificed the exchange in order to pile up on Anderssen's g2 pawn. Once that was sufficiently defended, he sacrificed the other exchange to allow his Queen to access the White King. However, as Anderssen correctly calculated, there was no checkmate. He was free to plant his Rook on the 7th rank, deal with whatever checks Mongredien threw at him, and then he'd be the one up material with the better game.

That's exactly what happened. Once Mongredien ran out of checks, he was forced to trade Queens, at which point Anderssen's Rook was the best piece on the board. A very rough match for Mongredien, who I'm sure was beating himself up over the over-zealous decisions of this game.

Round 7: vs. James Hannah

Another British amateur whose accomplishments are unknown to me. Opinions of him seemed to have put him in a similar bracket as Valentine Green, if that means anything.

Anderssen returned to his favourite opening from before, the Sicilian, which Hannah didn't attack correctly. An early f4 was refuted through Anderssen's exploitation of a pin along the a7-g1 diagonal, something Hannah suffered under the entire game. The Englishman's tactical senses weren't where they needed to be, and Anderssen soon won a piece. A short, mostly straightforward game from Anderssen was just what he needed after the intense previous match.

Round 8: vs. George Alcock MacDonnell

Finally, someone significant enough to have a picture (or a portrait, in this case).

George MacDonnell (not to be confused with Irish chess legend Alexander McDonnell, who had died in 1840) was among the many strong chess playing clergymen of England. It's impossible to talk about his achievements because his earliest games come from 1862 (outside of 3 I found against Samuel Boden from 1860-61), but his name will come up again.

I put this game right after the Hannah game because it features the exact same opening, thought MacDonnell made the "correct" 7th move (correct as in, according to contemporary theory). Anderssen got his Knight to e4 rather quickly, and this made his job of stopping MacDonnell's Kingside attack much easier. Combined with a pin along the exact same diagonal as last game, Anderssen overwhelmed the center with insane efficiency, easily deflecting MacDonnell's attempt at aggression and trampling him underfoot about as easily as anyone else.

Round 9: vs. Joseph Henry Blackburne

That picture of Blackburne is from when he was much older, probably about 1890. He was only 19 at the time of this event, but pictures of him from that era don't exist (as far as I know). "The Black Death" will be appearing in this series many, many times in the future, so let's look at his first entry to the saga.

A French Defense was Blackburne's choice for this game, and the players chose an especially symmetric setup. Blackburne's play was solid for the first few moves, though he made a slip with 15... Ba5, allowing Anderssen to plant a Knight on d6. He further miscalculated when he allowed Anderssen to take the b7 pawn, only realizing after the fact that the pawn could not be recovered. These weren't the biggest mistakes anyone had made against Anderssen, but they were somewhat unnecessary.

I think that Blackburne's mental state is what lost him this game. At only 19, facing off against the world's strongest player must have been intimidating, especially knowing that he had the worse position. Anderssen gradually made progress, won a second pawn, and converted the endgame without issue. A staggering 9th consecutive win from Anderssen, whose chances of winning the entire tournament were sky-high.

Here's another snippet from the tournament book, talking about the situation after the first two weeks of play:

As mentioned previously, Löwenthal would drop out at this point, so Anderssen's closest rival was Louis Paulsen - this shouldn't come as a surprise, if you look at the Edo rankings and consider that Paulsen was the most recent BCA champion. However, we have one game we must talk about before seeing the German giants square off on the chessboard.

Round 10: vs. John Owen

Perhaps I shouldn't have stretched it so much... The original photo was a square, it would've looked very out of place amongst the other photos. Anyway...

John Owen was another member of the chess-playing clergy, arguably the strongest from that group. His tournaments thus far included the "minor" tournament at Manchester 1857, a similar knockout event as its sibling that we covered in chapter 4. He also entered the Birmingham 1858 tournament, where we covered his loss to Löwenthal, or at least the one surviving game. The Owen Defense (1. e4 b6) is indeed named after this man, as he defeated Paul Morphy in 1858 with it.

With White, Owen gave us our first (and only) 1. d4 game of the event. Anderssen tried the Dutch Defense as it was considered the most aggressive response, and Owen threw out the popular Staunton Gambit (2. e4). This game certainly wasn't a good one to show off whatever merits the opening may possess, as Owen's compensation for the pawn was questionable at best; Anderssen castled into a somewhat drafty position, but he was also in a good position to go after Owen's King.

It became clear quickly that it was Anderssen who was on the attack, which certainly isn't a fun situation to be in if you're the one who sacrificed the pawn. His Queenside pawns stormed the White King's position, and as it opened up, it seemed like Anderssen was only a few moves away from winning at any time.

However, Anderssen made a few strange decisions with his Knight, moving it away from the attack and giving Owen time to consolidate. Once he did, the weaknesses of Anderssen's King were very apparent, and it was his turn to defend. His pieces were incorrectly placed for defense, however, and Owen broke through to hand Anderssen his first loss of the tournament. A game he certainly shouldn't have lost, but a fair one to prove that he is, indeed, human.

Round 11: vs. Louis Paulsen

The matchup that everyone was waiting for. Not only had Paulsen proven himself to be among the strongest European players in recent years - winning the Bristol 1861 tournament, giving multiple blindfold simuls like the one at this congress (where he scored 6.5/10), and so on - but he had lived up to that reputation at this tournament. I don't know exactly what his score was, but I do know that he only lost one game, to Serafino Dubois (who was Anderssen's final opponent). For all we know, these two were tied at this point, and this game was essentially going to decide the winner of the tournament.

Anderssen returned to the Ruy Lopez, this time opting for his favourite 4. d3 variation. When Paulsen retreated his Knight to thrust forward with f5, Anderssen confidently responded in the center, preventing Paulsen's expansion and leaving him cramped. Anderssen kept this up for much of the early game, hindering Paulsen's expansion, denying counterplay, and utilizing multiple pins to make everything uncomfortable. It was a quite modern approach from Anderssen, all things considered.

Eventually, as is often the case in such awkward positions, Paulsen blundered, as his 24... Qh8 simply dropped material, and Anderssen finished the game with some nice tactics. A rather lopsided game, and one that practically handed Anderssen the victory, provided he could get past the final obstacle.

Round 12: vs. Serafino Dubois

Serafino Dubois was the strongest player from Italy, a country that used slightly different rules than the rest of Europe for quite a while. Dubois was used to the more common rules, however, writing many works on opening theory and playing a mean game of chess on his own.

The pair played a handful of King's Gambit games outside of the tournament, and Anderssen employed one again for this final round. Dubois tried to return the pawn quickly, but in doing so he did nothing to prevent Anderssen's rapid development. As Anderssen got everything he wanted, Dubois fell into another trick, this time costing him a full piece. Alas, we cannot seem to escape the anticlimactic final game, irrespective of which format is used (and I know that this was the last game Anderssen played, so there's not much to be done).

Conclusion

I made that in Excel, with only the decisive game being recorded. There were a lot of forfeit wins, along with games being unrecorded, so many of those games won't be available to look at. Still, those are the results as recorded in the tournament book.

With Morphy's retirement being mostly accepted, Anderssen's position as the strongest player in Europe (and by extension, the world) had officially been restored. He would, after the congress had mostly concluded, play a match against Louis Paulsen (+3-3=2). While this tournament would represent a good showing for the all-play-all format, it would take some time before it was streamlined and universally adopted; we'll see that a little more in the next entry.

Apologies for the delay since the last installment, real life is crazy sometimes, and these can be a bit of a slog to write without enough motivation. I should be good to go now, though.

Chapter 5 (contains links for 1-4)