Three Old Songs

I'd been having a discussion of sorts with a friend of mine about the song most commonly known as Barbara Allen. I first heard the song on my The Everly Brothers' Songs Our Daddy Taught Us cassette tape a couple decades ago. But before that discussion even came up I had been looking into a different song I know as Little Matty Groves. I learned to play this one from listening to Doc Watson on his album Home Again! which I have in vinyl. Chess.com member, @robbie_1969, turned me on to a song called Twa Corbies. At the time I couldn't understand the lyrics well enough to realize what I was hearing. As it turned out, I'm familiar with an English version, one I had learned to play, again decades ago, from listening to Peter, Paul and Mary's In Concert album which I also have on vinyl. The English version is called Three Ravens.

So around the same time I found myself involved with three ancient songs of British origin.

I got my first acoustic guitar before I was 12 and taught myself the chords from a book I found in the library appropriately called 1001 Guitar Chords. I found other books that taught me some basic finger-picking techniques such as Travis, arpeggio, Carter family style, which I practiced religiously. I couldn't read music at all at the time, so I mostly figured out songs by listening to recordings and trying to duplicate them. We had an eclectic ton of old vinyl 33 rpms lying around. That's where I discovered ballads which I fell in love with. Ballads tell stories, mostly old stories passed down over years, often spanning centuries. Like most folk music and unlike books, they have more an oral than a written tradition. Because of that they belong to the people and not to some generally unknown author. They each change considerably, but usually retain the same basic tenor. Even when written down and published, they do not become set in stone and we can find extreme variations even in print.

Like most people, I just accept songs as I find them. But sometime, when I think about their possible antiquity and almost ubiquitous presence, I get curious about how they got all the way from Merrie Old England (or wherever) to my fretboard.

Three Ravens obviously underwent some changes, the least of which was numeric. Barbara Allen and Matty Groves, however, present the widest variations in names, lyrics and even melody.

In discussing Barbara Allen, my friend brought up the salient points of mythic themes -or lasting stories- becoming part of the human consciousness, or at the very least an expression of shared human traits - love, fear, needs and desires with this universality transcending times, locations, culture and individual differences. The fact that they express what we share brings us closer just as their centuries of endurance attest to their universality.

I'm sort of a simple person. The face value is usually enough for me. That being so, I don't want to over-analyze these ballads but rather relish them for what they appear to be and maybe examine a little of their long journey from the past to the present.

One thing of note: all these ballads are as well known in America (the US) as they are in England or Scotland. Since the U.S. was once a British colony populated by British individuals, it only makes sense. In the South -and Appalachian Mts., a reservoir for these songs - there's a strong Scottish heritage.

I'll add a version of the lyrics to each song at the end of this already cumbersome blog entry.

Ballad I

Ballad I

Three Ravens

Above was my first exposure to the ballad of the Three Ravens.

But the earliest mention of this ballad was in 1611 and it was obviously much older than that. The aptly named Thomas Ravenscroft, "a Musical Compser of the Time of King James First," included it in his deliciously named book of musical lyrics, "Melismata. Musicall Phansies. Fitting the Court, Cittie, and Countrey Humours. To 3, 4, and 5. Voyces." -- "To all delightfull, except to the Spitfull. To none offensive, except to the Pensive."

Three ravens are discussing feasting on the remains of a dead knight they found. But the knight's body is protected by his dog and hawk, soon joined by a small pregnant doe. The doe tenderly carries away the knight and buries him, depriving the carrion of their meal.

A couple centuries later we find a derivate of Three Ravens in Sir Walter Scott's Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802), called Twa Corbies.

Walter Scott wrote as a preface to Twa Corbies (and Three Ravens):

This poem was communicated to me by Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe, esq., jun., of Hoddom, as written down, from tradition, by a lady. It is a singular circumstance, that it should coincide, so very nearly, with the ancient dirge, called the Three Ravens, published by Mr Ritson, in his Ancient Songs; and that, at the same time, there should exist such a difference, as to make the one appear rather a counterpart than copy of the other. In order to enable the curious reader to contrast these two singular poems, and to form a judgment which may be the original, I take the liberty of copying the English ballad from Mr Ritson's collection, omitting only the burden and repetition of the first line. The learned editor states it to be given "From Ravencroft's Melismata. Musical phanysies fitting the cittie and countrey, humours to 3, 4, and 5 voyces, London, 1611, It will be obvious (continues Mr Ritson) that this ballad is much older not "only than the date of the book, but most of the other "pieces contained in it." The music is given with the words, and is adapted to four voices.

Apparently Scott and Ritson felt Twa Corbies wasn't a form of Three Ravens, but rather a counterpoint or a harsher answer to that somewhat benign song.

In the grim Twa Corbies (Two Crows), the two crows are heard having a conversation about dining upon a dead knight they found. His dog and hawk left him and his lady found a new lover. The crows slaver over how they'll sit on his white neck bone and peck out his eyes, then take his hair to make a nest. They also mockingly opine how the wind will blow across his bare bones forevermore.

This is the example @robbie_1969 gave me, and it's a fine one. He also mentioned The Cruel Sister. I didn't include that ballad here separately (other than this aside) though it would definitely fit. Originally, at least as far as anyone can show, it was called The Miller's Melody. The earliest "two sisters" title, as it's most commonly known, was The Twa Sisters o' Binnorie.

The Monthly Chronicle of North Country Lore and Legend, 1889, contends:

The popularity of this ballad extends over a period of nearly 250 years, the earliest copy known being a broadside in the possession of Mr. Rimbault, entitled "The Miller's Melody," "printed for Francis Grove, 1656." It afterwards appeared in "Wit Restored," 1658, as "The Miller and the King's Daughter."

Mr. Jameson and Sir Walter Scott both designated this a parody. Prof. Ohild, of Boston, U.S., however, contends that It is not, although he admits that '' two or three stanzas are ludicrous." He also states that the same story is to be found in the Icelandic, Norse, as well as in the Swedish and Danish languages, and a nearly related one in many other ballads or tales of Germany, Poland, Lithuania, &u. The professor's evidence is weighty in the matter, as his edition of English and Scotch Ballads, published in eight volumes in 1861, is the best collection yet published, and is specially valuable on account of containing nearly every British ballad or ballad version worthy of preservation.

There are two melodies to which the ballad has been sung, and the one we give is that which is used in the Reedsdale and Liddesdale districts. It was sent by James Telfer, of Saughtree, in 1857, to Mr. Robert White, of Newcastle. The other melody is also beautiful, and was sung by Mr. Sinclair in giving his Scottish ballad entertainments about fifty years ago. It may be necessary euphonite gratia to remark that the burden is pronounced BinnSrie, and not Binnorie, as it was accented in a modern ballad some time ago.

The miller, the harp and the drowned sister

The miller, the harp and the drowned sister

This figuring would put Twa Sisters around the same time as Three Ravens. It's a horrid, though eerily fascinating liitle ballad of two sisters who fall in love with a knight. He courts both sisters but loves the younger. The jealous older sister lures the younger one to the river and pushes her in. She drowns but her body is discovered by a miller. He anguishes over her and makes a harp from her sternum and other body parts. The harp is played in he dead girl's father's hall where it identifies the older sister as her murderer.

Ballad II

Barbara Allen

Despite the apparent popularity of the above three ballads, musicologists consider none to be as popular, copied or widespread as Barbara Allen.

as I first heard the song

possibly the most ethereal and beautiful rendition

The first known recorded reference to the ballad was given in the Jan. 2, 1666 diary entry of Samuel Pepsys:

Up by candlelight again, and wrote the greatest part of my business fair, and then to the office, and so home to dinner, and after dinner up and made an end of my fair writing it, and that being done, set two entering while to my Lord Bruncker’s, and there find Sir J. Minnes and all his company, and Mr. Boreman and Mrs. Turner, but, above all, my dear Mrs. Knipp, with whom I sang, and in perfect pleasure I was to hear her sing, and especially her little Scotch song of “Barbary Allen;” and to make our mirthe the completer, Sir J. Minnes was in the highest pitch of mirthe, and his mimicall tricks, that ever I saw, and most excellent pleasant company he is, and the best mimique that ever I saw, and certainly would have made an excellent actor, and now would be an excellent teacher of actors.

Barbary Allen was obviously already a well known and popular song by then but it would be nearly another century (1759) before another reference appears. Oliver Goldsmith called the song, The Cruelty of Barbara Allen.

My present enjoyments may be more refined, but they are infinitely less pleasing. The pleasure the best actor gives can no way compare to that I have received from a country wag who imitated a quaker's sermon. The music of the finest singer is dissonance to what I felt when our old dairy-maid sung me into tears with Johnny Armstrong's 'Last Good Night,' or 'the cruelty of Barbara Allen.' --from the essay: Happiness, in a Great Measure, Dependent of Constitution.

I was fortunate to discover the highly detailed masters thesis presented by Sister Mary Riley, B.V.M. at Loyola University in 1957 (Barbara Allen in Tradition and in Print). She mentions that while many variations exist, nearly all of them agree on certain fundamental details: "A dying young man sends for Barbara who takes her time about coming to his deathbed. When she sees him, she recognizes his condition immediately with the words, 'Young man, I think you're dying,' to which he replies that she alone can save him." She refuses and leaves him either dead or dying. "Frequently, she accuses him of slighting her by ignoring her at the tavern when offering wine or toasting the 'other girls.' Less frequently the slight is offered at a dance hall or in another place. As she leaves him she hears bells, or birds, reproaching her for her cruelty and she repents and dies of a broken heart."

Manchester England Broadside c.1800

Manchester England Broadside c.1800

London Broadside, also c.1800, but with somewhat different lyrics

(click image for a larger view)

[Broadsides were single, one-sides papers -such as posters, advertisements - cheaply made and distributed. There was a sub-genre called Broadside Ballads, attesting to the popularity of that music, usually sold of the street for a penny. ]

Barbara Allen has had so many variations (in the locale mentioned, the time of year, the names of the lady and the man and most of the other details) it would take a book just to list them all. But the one variation that caught my eye is the Rose/Briar ending... evident in many of the variations found in the United States but absent in the early English/Scottish songs.

Here is the ending from Barbara Allen (from the version used by Joan Baez)

Sweet William was buried beside her,

Out of sweet William's heart, there grew a rose

Out of Barbara Allen's a briar.

Till they could grow no higher

At the end they formed, a true lover's knot

And the rose grew round the briar.

Several English Literature texts I surveyed claimed that while there are many variations to Barbara Allen, the one common aspect is the rose-brier/briar motif. This is clearly wrong. Most English and Scottish variations I looked at didn't possess the rose-briar ending, while most American lyrics did. Another ballad, which can be traced at least as far back as 1765 and probably existed long before is Lord Lovel. Lord Lovel goes on an adventure to foreign lands leaving his Lady Nancy behind to wait for his return. He's gone for a long time and when he returns, he immediately seeks her out. But she had pine away and died. The ending is eerily similar to the rose-brier ending we find in many Barbara Allen lyrics:

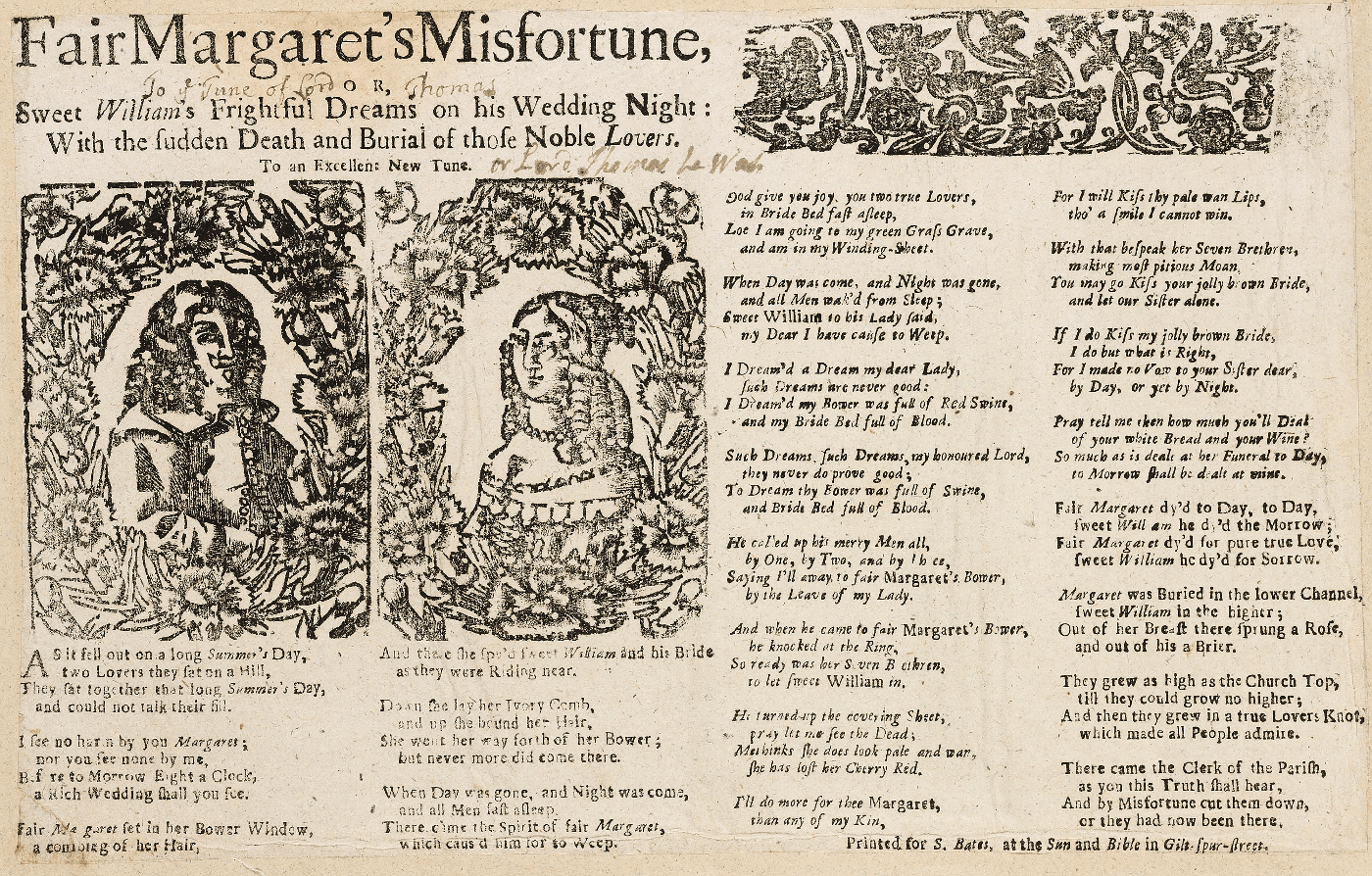

Yet another ballad, Fair Margaret and Sweet William, dating back to at least 1611 (since fragments of the ballad are " twice quoted in Beaumont and Fletcher's Knight of the Burning Pestle, 1611" -Child. (Curiously, Samuel Pepsys, who, as noted above, loved Barbara Allen, hated this play), contains the rose-briar motif.

a broadside from London c.1720

a broadside from London c.1720

(click image for full size)

Ballad III

Little Matty Groves

This is the album where I first heard Little Matty Groves

Now Matty Groves, which like most old ballads and ice cream, comes in many flavors, is a strange song to me.

Matty (in the Doc Watson version) is planning a tryst with Lord Daniel's wife. A foot page hears him bragging about it to one of his friends and runs off to tell Daniel, hoping for a reward. Daniel, who is out on a hunting trip (as I picture it) returns home unexpectedly and finds his wife and Matty in flagrante delicto. Seemingly Daniel would be justified in simply killing Matty (who is naked) as he lay but instead let's him get dressed. Matty cries that he's unarmed, so Daniel not only gives him a sword, but his finest one and lets Matty strike the first blow, which "wounded Lord Daniel sore." Daniel, severely wounded and therefore handicapped, kills Matty. Then he gives his wife a chance to profess her love for him - as if looking for an excuse to spare her- but she's unrepentant and tells him to dig a grave for her, putting Matty is her arms while Daniel, whose wound must have been mortal, should be buried at her feet.

It seems as if the only truly honorable person in this story is Lord Daniel, yet he ends up the worst treated.

Like Fair Margret and Sweet William, this ballad, as Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard is found in Percy's 1765 Reliques and Percy mentions that it's also referenced in Beaumont and Fletcher's Knight of the Burning Pestle, 1611. So, it's quite old. Lady Barnarde is the wife of Lord Barnarde. Child, in his English and Scottish Popular Ballads, names them Little Musgrave and Lord and Lady Barnard.

Child's version differs slightly from Doc Watson's Appalachian version, particularly starting when Lord Barnard finds the lovers:

An even different ending, as well as a different confrontation scene, can be found in the variation called Little Matha Groves (I found this in the 1919 book by William Roy Mackenzie,The Quest of a Ballad :

Little Musgroves and Lady Barnard c.1670

Little Musgroves and Lady Barnard c.1670

(Click image for full size)

What information pertains

The thought that life could be better

Is woven indelibly

Into our hearts and our brains.

Paul Simon - Train in the Distance

note: all broadside images were found at Broadside Ballads Online

Clicking on the ballad will open the lyrics in a new window:

- Three Ravens

- Twa Corbies

- Twa Corbies (Anglicized)

- Twa Sisters o' Binnorie

- Barbara Allen

- Fair Margaret and Sweet William

- Little Musgraves and Lady Barnard

- Little Matty Groves