Unbridled Opulence

I'm offering a backstage pass to a production featuring some of the obscenely rich social elite during the famed Gilded Age of turn-of-the-century America. The backdrops feature scenes of New York City and Lakewood, N.J. It's a rags-to-riches story that examines the wantonness of wealth and and the vacuousness of social pretense. Appropriately enough, my fascination all started with a chess game...

I saw this illustration the other day. I'm quite familiar with it, so it wasn't the image itself but the caption that caught my eye.

It was described as a Living Chess game at the home of Jay Gould. This is incorrect.

I did a search for the painting and elsewhere saw that the game was supposedly played at the estate of F. Jay Gould —also incorrect.

The Living Chess game portrayed here occurred a dozen years after the death of Jay Gould at a place that didn't exist during his lifetime.

First, some background -

Jay Gould, as most people know, was probably the richest and possibly the most despised man in America during his lifetime. This prototypical "Robber-Baron" built a railroad empire, crushing the competition, leaving havoc in his wake, ruining lives and businesses. As a financier, Gould tried to corner the gold market on Wall Street with the so-called Gold Ring which triggered the Black Friday wave of financial destruction and later he became involved with Boss Tweed in another corrupt affair. When he died, he left a fortune of close to 100 million dollars— an automatic inflation calculator estimated this to be worth $2,770,835,164.84 in today's currency —to his six heirs.

Jay Gould died in 1892.

Now let's back up a few years, specifically to Tuesday night, November 25, 1884. Jay Gould and his 20 year old son, George, were attending the opening night of a Broadway comedy entitled, "Love on Crutches" at "Daly's Theatre" on Broadway and 30th Street. One of the female lead actresses, Edith Kingdon, a relatively new-comer to the stage, particularly to such an established theater as that owned by Augustin Daly, caught the eye of the audience but more relevant to this story, caught the eye of a certain George Gould.

The story goes that the two experienced actresses from the three leading female roles came out for a curtain call. Edith Kingdon, a virtual unknown at this point in time, went to her dressing room to change into a different gown. The audience started chanting, "Kingdon! Kingdon!" and she was frantically summoned to come to the stage. But she was only half dressed. She tried to hastily cover up, but the improvisational shawl proved inadequate. Instead, she simply poked her head through the curtain and smiled at the audience —an act that seemed endearingly effective.

Daly's Theatre

George arranged for a meeting with Miss Kingdon and within three months he proposed.

Edith had been described by contemporaries as beautiful, vivacious and saucy. George had been quoted as having been attracted to her character as must as to her outer beauty. He saw a young woman who took up acting to support her mother, impoverished after her husband deserted her, yet displayed unparalleled refinement. Whether Edith married Gould for his money or for love, she apparently was a good wife on whom he continued to dote. Together they had 7 children.

m

m

George's mother, Helen Day Miller Gould, was a socialite of the highest order. She was aghast at the idea of George marrying an—an—an actress! But Jay Gould, who had absolutely no social pretenses, condoned it and his wife reluctantly acquiesced to the engagement although it was kept rather quiet. The wedding itself was a small, somewhat private and sedate affair at Jay Gould's looming summer palace, Lyndhurst, located at Irvington-on-the-Hudson. The press was only informed after the fact.

George worked for his father, foregoing higher education for a Wall Street position —which his father bought for him when he turned 21— then was granted seats on the boards of various companies and became president of a handful of railroads and about an equal number of telegraph companies. Where Jay Gould was ruthless and all-business, his son was convivial and more concerned with society. George liked yachting, polo, tennis, golf, hunting, fishing and, of course, chess.

"It will be a genuine surprise for most of our readers to learn that the eminent financier, whose likeness we bring on another page, is a devotee of Caissa and The American Chess Magazine takes just pride in being first to make this announcement. In Europe, affiliations between Haute Finance and chess have been many, and the name of Baron Albert de Rothschild is a household word to amateurs; American chess players now can point with equal pride to George Jay Gould, who is one of those who, by reason of modesty, have never intruded themselves upon public notice by seeking reputation through display of their abilities. Our picture shows Mr. Gould in the railroad car coming from his home to the city studying some game." —American Chess Magazine June, 1897.

When George and Edith married they were given a mansion at 857 5th Ave. at the corner of 67th St., NYC. This they demolished in 1906 to build a much larger residence designed by the current en vogue architect, Horace Trumbauer, who had also designed the Phila. Museum of Art, the Ritz-Carlton in Phila. and the Harvard main library.

When Jay Gould died in 1892, he left an estate appraised at $84,309,258, plus the $12,000,000 in Louisiana timberland that bypassed his estate. The money was in six trusts for each of his children. George was the designated executor of the estate and head of the family and used that position to further enrich himself.

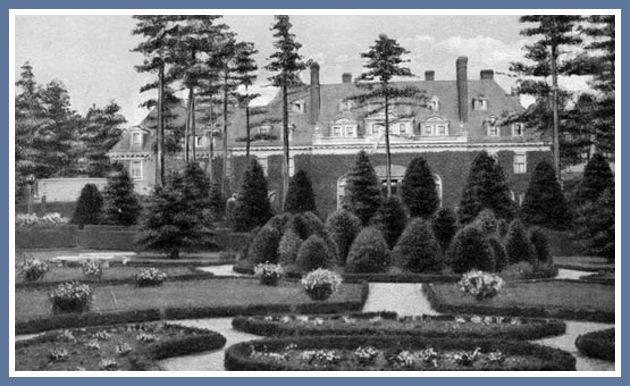

In 1896, George and Edith started construction on a 200 acre tact of lane in Lakewood, N.J. The compound would be called Georgian Court (after George). Full construction took over a decade, but they moved into the main building in 1897. The estate was designed by Bruce Price. Price was most noted for having been engaged by Pierre Lorillard, the tobacco heir who had bought 7000 acres in Orange County, NY, to design the original 13 "cottages" (read: fabulous mansions) and a clubhouse for his proposed Tuxedo Park, a residential area for the wealthy and social elite. However Georgian Court was considered Price's crown jewel. Price also designed the Italian Garden, the Sunken Garden and the Formal Garden. Later, as a birthday present for Edith, Takeo Shiota, who incidentally designed a Japanese Garden for Tuxedo Park, created a Japanese Tea Garden.

Georgian Court

Georgian Court

Of the many amenities, the property included a free-standing Casino and Casino Court whose oval center was larger than Madison Square Garden. Around this monstrosity were indoor tennis courts, squash courts, a 25'x60' swimming pool, Turkish Baths, Russian Baths, " a steam room, a 'bachelors' hall' containing accommodations for twenty-five men," as well as a gymnasium, a bowling alley and billiards room. The grounds included a 9-hole golf course, three polo fields, a huge riding arena and riding school, a stable of award-winning horses, hunting facilities and stocked ponds. The house had forty bedrooms, 20 bathrooms, a music room, a club room, an automobile room and even a theater for staged performances.

During a winter social event at Georgian Court on Jan. 8, 1900, three different plays were performed: A Pair of Lunatics, The Marble Arch, and Edith Wharton's, The Twilight of the Gods which featured Edith Gould in the lead female role (above).

After the performances, an elaborate meal was catered by Delmonico's restaurant, followed by a most curious event:

a sturdy Santa Claus came in bearing a large white ball, which, on being deposited on the floor, opened and revealed a little girl, dressed as a fairy, who stepped forth and took upon herself the distribution of the favors, consisting of gold horse-shoes, golf-sticks, and other bits of jewelry, quaint toys, and ingenious electrical devices.

The only other reported instance of Edith Gould giving a performance since her retirement from the stage was on Jan. 20, 1908 when she gave a semi-pubic performance as the female lead opposite Kyrle Bellew - for Mr. Frederick Townsend Martin's tea (for the London sculptor George Wade and his wife)- in Mrs. Van Vechten's Divorce Dance at the ballroom of the Hotel Plaza. Mr. Martin, a writer and advocate for the poor, had a letter published in the NY Times the day before warning attendees that they should be prepared to remove their hats, a requirement for attendance, so as not to obstruct anyone's view.

l

Kyrle Bellew and Edith Gould in Mrs. Van Vechten's Divorce Dance

the above illustration came from The Sphere, August 14, 1904. It was a two page spread (hence the distortion in the center) but there was no accompanying article. However, there was a caption:

Living chess was player recently at Mr. George J. Gould's casino at Lakewood. The games were played by Dr. Charles L. Lindley and Professor F. M. Roser. The chess pieces, represented by thirty-two boys handsomely attired in costumes of the fifthteenth century. The pawns were costumed as esquires and the kings, queens, knights and rooks were costumes of their ranks. Two trumpeters, attired as heralds, announced each move at it was made. At the end of the game the players who were beaten knelt in submission to the victors.

The Chess Amateur, of Feb, 1907 recognized the colored illustration from the beginning of this presentation with the following:

There is a most interesting account in Le Petit Journal of an entertainment that recently took place at the magnificent palace of Miss Jay-Gould, situate at Lakewood, New Jersey. Two celebrated Chess players, Mr. Charles Lindley and Professor Roser, were invited to play a game of Chess on a Chess board the like of which they had never seen before. The pieces and pawns were represented by thirty-two lads, dressed in wonderful costumes of the fifteenth century period. The paw ns were valets, waiters and pages. The knights were arrayed in beautiful armour, like that worn by the ordonnance gendarmerie [la gendarmes d'ordonnance de la Garde impériale —batgirl] of Charles the Bold. This was worked, festooned, and embellished with flowers, covered with carvings and golden emblems. The castles were represented by horsemen equipped from head to foot, with battlement helmets. The bishops were clad in superb vestments made of precious material. The queens had full robes of heavy brocade. The kings moved about with crowns on their heads, and sceptres in their hands, their costumes being covered with precious stones. The heralds arrayed in dress of the period, announced the commencement of play by a flourish of trumpets, and at the end of the game the figures of the conquered came and knelt before the conqueror, who with a benevolent and lovely gesture, ordered them to arise again. This little folly, of which the dresses alone cost the mere bagatelle of 100,000 francs, proved a successful affair.

Dr. Charles L. Lindley, who would later found the Beverly Hills Chess Club (in the 1920's—Bill Wall) which attracted many film celebrities and would be in its heyday the strongest chess club in Southern California, organized this living chess game for the benefit of the Lakewood Boys Club (NY Times 4-17-1904). Francis M. Roser was an elusive chess player from New York City. He had apparently been long retired from the game by this time.

Appleton's BookLovers Magazine reproduced the Sphere illustration in Nov. 1904:

Everybody's Magazine, Oct. 1904, also included the short write-up below about this living chess game. Living Chess wasn't a rarity, so the attention given to it must have been more about who sponsored it and the opulence of the production:

Master chessmen play a game that in the abstract resembles a spectacle produced last May at Georgian Court on the Gould Estate at Lakewood, N. J. In the Casino there, an immense chess-board was laid down and the chess pieces were represented by living men in costumes of the period of Charles IL Under the direction of two players elevated on platforms above the board, the living chessmen moved about from square to square and a game was played out for the edification of a wealthy assembly. But in the great game that the masters are playing among themselves, the living chessmen are not mere automatons directed by an overseer. Each follows his own more or less devious course about the greater board, capturing a man here or being captured there, and he who would ultimately place the king in check must be endowed with tremendous mentality, for some there are among these masters of the game of intellect who possess powers that seem to border on the uncanny.

N.Y. Times of April 16, 1904

James Hazen Hyde, the majority stockholder of Equitable Insurance gave an over-the-top costume ball on Jan. 31, 1905. Before we go over the extravagances, it might be interesting to note that this ball, which cost $200,000 (about $4 million today) almost resulted in his downfall. Members of the Equitable board, which included such well known power brokers as J.P.Morgan, Henry Clay Frick and James Waddell Alexander, were using all sorts of unsavory means to dispose Hyde and gain control of the company. One of their accusations, which was proved false, was that Hyde charged the cost of the costume ball to Equitable. The weight of all their allegations almost caused a Gould-like Wall Street panic.

. . . but back to the excesses of the Ball:

Held on the second and third floors of the eloquent Hotel Sherry restaurant, 600 people attended, all dressed as required in costumes meant to "recall the splendor of Versailles, the reign of King Louis, and the time of Marie Antoinette."

According to Metropolitan Magazine, "Even the waiters and servants were in costume, with great white wigs, red and blue uniforms, white silk stockings and a plentiful supply of gold braid and silver lace."

Music was provides by the Metropolitan Opera House Orchestra. People watched a theatrical performance of Entre Deux Portes and a debutante dance, costumed by the same Opera House and trained by professional ballet while the rooms were decorated to mimic the famous gardens of Versailles.

The real measure of unchecked spending can be found in once-poor Edith's jewelry. At that time pearls were considered more valuable and desirable than diamonds and Edith was the queen of pearls. George gave her a pearl necklace from Tiffany's supposedly valued at $1 million at the time. Her typical jewelry ensemble can be seen in the Edith Mary Kingdon composite image earlier on the page.

As one can see in her estate valuation, her entire collection was appraised at $1 million dollars (as opposed to a single item). According to an automated inflation calculator, a million dollars in 1921 would be 15 million today.

When they were first married, George noted that in addition to Edith's beauty, he was attracted to her personality. However, after 7 children and a life of self-indulgence, Edith started putting on a lot of weight and George's eyes started roving. On Dec. 29, 1913, George went to see a Broadway musical, “The Girl on the Film.” It only ran for a month and a half (64 performances), but it seems George, once again, was more focused on an actress than the production. The actress, who played Olivia, was listed as Vere Sinclair. Vere was apparently short for Guinevere. In 1914, Miss Sinclair —although her name seemed to be Guinevere Jeanne Sinclair, all the papers called her "Alice Sinclair" for a reason I can't ascertain— became George's mistress. He put her up in a nearly 30 acre estate on Manursing Island in the New York Sound, a place he visited by yacht every weekend. Vere bore him three children, two girls and a boy.

the Gould estate on Manursing Island as it looked in 1926

In 1920 the Goulds expanded their 9 hole golf course to 18 holes and the following year, in late November, 100 golfers who had been invited to take part in the annual 3-day Autumn Golf Tournament at the now "Lakewood Country Club" at Georgian Court, showed up for what was to be an unexpectedly somber event. On the Sunday just before the tournament (Nov. 13, 1921), as Edith, who was playing a round with her husband, teed off on the 5th hole, she suffered a fatal heart attack. Many reports say she was in perfect health at the time, but others claim she had a long-standing heart condition. Still other reports claim he was wearing a rubber undergarment meant to slim her figure and induced weight loss —perhaps one of these:

George's affair was an open secret of which Edith had surely been aware. She was taking weight loss medications, exercising vigorously and possibly wearing contraptions such as the rubber suit in an effort to regain her husband's attentions. These things most likely helped pushed her to an early death at age 57.

George, after a six-month period of grieving, married Miss Sinclair (May 1, 1922).

The following clipping shows how his bride was called Alice. This is true of every newspaper I examined, including the NY Times.

George and Vere/Guinevere/Alice were married exactly 1 year and 15 days. Due to the backlash from marrying his mistress, particularly after such a short time after his socially-popular wife had died, the couple felt compelled to leave America, finally ending up in Scotland. But while on vacation in Egypt, George took sick so suddenly after visiting the tomb of King Tut in March 1923 that rumors of "King Tut's Curse" circulated around him. Returning to the Villa Zoralde in Roquebrune-Cap Martin on the French Riviera where he and his wife spent the winter, he quickly died of pneumonia.

George, who had been a spendthrift his entire life, left just a little over five million after taxes and creditors were paid to his heirs —7 children by Edith and 3 children by Guinevere (although her children had to sue and even then ended up getting 50% less than their half-siblings). Georgian Court was sold to the Sisters of Mercy order and is now the site of Georgian Court University.

The mind-boggling fortune of the richest man in America, Jay Gould, was diluted and dissipated into a relative pittance. The Gilded Age ended tarnished and worn out.