A Century of Chess: St Petersburg 1909

The last tournament of the decade and the most famous. The vast majority of international tournaments of the era were in the German-speaking world and had a distinctly bourgeois flavor. Tournaments in Russia were rare and a treat – they were unmistakably aristocratic. Pyotr Saburov, a prominent diplomat, organized the 1909 tournament as a memorial for Mikhail Chigorin, who had died the previous year. The tournament attracted the cream of international chess and the prize fund was topped off with a nice addition from the tsar himself.

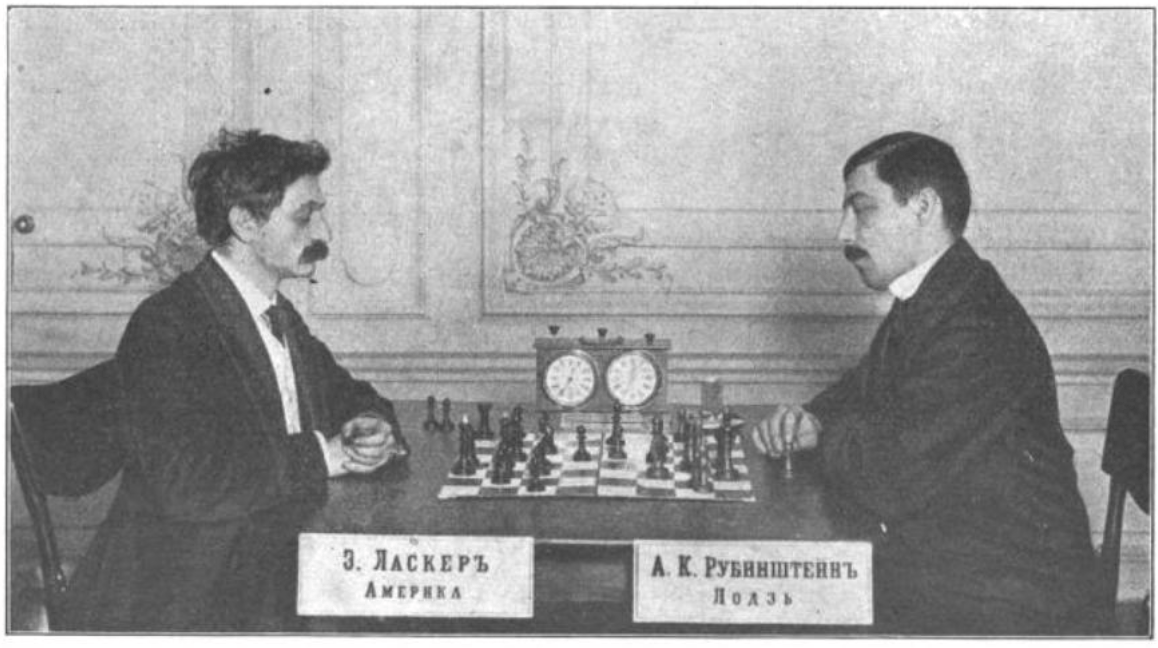

The tournament had the air of a victory lap for Emanuel Lasker, who had ended his quasi-retirement of 1900-07 and was winding up a match series against his nearest rivals, decisively defeating Marshall, Tarrasch, and Janowski, and proving his superiority over the rest of the chess elite. At St. Petersburg, he was spectacular, winning 13 games against only two losses and three draws.

He celebrated his success by writing the book of the decade – St Petersburg 1909, in which he annotated all the games of the tournament. The book is most famous for Lasker’s bold claim in the introduction: “This is a book that is free from mistakes.” That’s a reckless thing for a chess annotator to claim – and would seem particularly foolhardy for someone who didn’t even have the opportunity to check his analysis against an engine – but remarkably, and this is a real testament to Lasker’s greatness, subsequent scrutiny has turned up few major errors in the book.

Dominant as Lasker was, Akiba Rubinstein was at the peak of his career and kept pace with Lasker with the same jaw-dropping +11 score – they tied for first, a full three-and-a-half points of the third-place finishers, which, as far as I can tell, is a record for joint domination of an event. Lasker’s wins were models of power play and tactical wherewithal, but Rubinstein’s were something else – works of art, in which, out of innocuous openings and sleepy middlegames, he kept finding subtle resources in the endgame.

The most famous game of the event – and of Rubinstein’s career – was his elegant win over Lasker, which made the case, forcibly, that Rubinstein was Lasker’s one true rival for the world championship.

As for the rest of the crosstable, Rudolf Spielmann put in his first world-class result – he had wildly uneven results over the first years of his emergence in international chess, but at St Petersburg he kept to Lasker and Rubinstein’s torrid pace for most of the tournament and only fell back with three losses at the end.

Duras was at his peak and had a very strong tournament, tying for third place with Spielmann.

Erich Cohn had one of his best results. The eccentric Russian player Fyodor Dus-Chotimirski had his claim to fame by beating both Lasker and Rubinstein. The story is that he was reading a Japanese translation (!) of Thus Sprach Zarathustra during his game with Lasker, and Lasker, distracted by Dus-Chotimirski’s insolence, played at less-than-normal strength. Schlechter, co-winner of the 1908 jubilee tournaments and already booked for a world championship match, was one of the tournament favorites, but he had the flu and scored only 50%. He did have the consolation of winning the brilliancy prize - robbing both Leó Forgács, in one of the best games of the his career, and Savielly Tartakower, who, even decades later seemed to be very annoyed about this, feeling that his win over Schlechter was more deserving.

It's surprising to look at the results of an international event and to see all these Russian names at the bottom of the crosstable. Russia (especially if one excludes the émigres and the Polish players) simply wasn't the powerhouse it would be even a few years later. Meanwhile, Austro-Hungary was close to its peak - sending a powerful cadre of Schlechter, Spielmann, Duras, Perlis, Forgacs, Vidmar (within a decade of the tournament over half that group would be dead or retired from chess). Russia had its consolations, though, in the concurrent Amateur Tournament, which featured the rising stars Rotlewi, Romanovsky, Verlinsky, and, above all, the 16-year-old Alexander Alekhine. Romanovsky recalled meeting Alekhine just before the tournament - a portrait of the chess master as a teenage brat - and being shaken by Alekhine's arrogance (which would soon find its way to the rest of the chess world). "I am almost certain I will take first, especially as the title of master will be conferred on the first prizewinner," Alekhine said. "With these gentlemen it is necessary only to play boldly." And, as so often was the case, Alekhine was able to back up his big talk - scoring +10 and finishing a point ahead of Rotlewi.

Part of the tsar's munificence was to bestow a Sèvres vase on the winner of the amateur tournament - and that vase became the prize possession of Alekhine's for the rest of his life. It was the sole object to accompany him when he left Russia after the revolution and was in his hotel room when he died in 1946.

Sources:

- Emanuel Lasker, St. Petersburg 1909

- Savielly Tartakower, My Best Games of Chess 1905-1954

-Taylor Kingston, Emanuel Lasker: A Reader

-Alexander Alekhine, My Best Games of Chess, 1908-1937

-Chessgames.com: St Petersburg 1909

-Sarah's Chess Journal, Encounters with Alekhine

-simaginfan, All Russian Amateur Tournament

-DonMcKim, St Petersburg 1909