And the Best Chess Player Ever is...

Since Bobby Fischer won the world title in 1972, many have referred to him as the best chess player who ever lived. But after Garry Kasparov became the youngest world champion ever at the age of 22, the ‘Best Ever’ designation gradually shifted to the East.

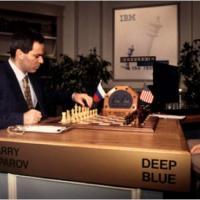

Yet in 1997, an amazing 6-game match took place in New York, culminating in a defeat for the world champion. Despite this loss, Kasparov can still lay claim to being the best chess player who ever lived because he was not defeated by a living player, but by a machine – IBM’s Deep Blue.

When I set out to write this blog, I was expecting to promote the concept that Deep Blue’s victory was actually a victory, not a defeat, for human ingenuity and intelligence because it was those unique human qualities that created Deep Blue. However, after studying all 6 match games and having read some commentary, I cannot write that blog because I do not believe this match represented such a victory.

To be fair, Deep Blue truly was an amazing accomplishment by the IBM team, assisted by GM Joel Benjamin and other chess consultants. Although he also criticized its weaknesses, even Kasparov did not hesitate to praise Deep Blue. Consider Kasparov’s statement that, “We have to praise the machine for understanding very deep positional factors,” and also his remark that an individual move in game 4, which resulted in a draw, was a “brilliant positional decision.”

GM Daniel King, who wrote a book on the match, describes Deep Blue’s 21st move in game 2 as “profound.” Susan Polgar said of the same game – by far its best – that “the computer played like a champion … Deep Blue played many moves that were based on understanding chess, on feeling the position.”

Let us look at that remarkable second game, a Ruy Lopez with Kasparov playing the Black side.

Several commentators have likened Deep Blue’s play in this game to that of Anatoly Karpov, who Kasparov had defeated to become the world’s chess champion. That the game was so special was all the more surprising because Deep Blue had played quite poorly in game one, which Kasparov had dominated.

The world champion had prepared magnificently for the match, which captured planetary attention. Chess computers excel at tactical calculation, easily outperforming their human opponents. Indeed, Deep Blue was able to consider 200 million moves per second (about 100 times faster than Deep Fritz 11 on my MacBook Pro).

Kasparov, understanding its strengths as well as its weaknesses, played a brilliant anti-computer strategy, frequently forcing the computer out of its openings book, and employing clever devices such as a pawn sacrifice in game 4 for positional advantage, where tactical strength is less useful.

I have mentioned already that Kasparov easily outplayed Deep Blue in game one before being defeated by it in game two. But there was more to game two than brilliant play by an automaton. It was discovered within 24 hours of the end of that game that Kasparov, who had resigned on move 45 had done so prematurely. Positionally, the game was actually a draw, which was possibly first noticed by players in Germany, who then informed the Kasparov team in New York.

Apparently, Kasparov had considered playing 45. …Qe3 in hopes of a draw by perpetual check after 46. Qxd6, but he resigned since he correctly calculated that the checks which follow were finite. However, the move that was discovered in the post-mortem was 46… Re8, which does lead to a perpetual check after several more moves.

Kasparov’s resignation was, in short, a blunder. That Kasparov could blunder away the draw is at least understandable on human terms, but a greater question remains unanswered. How could Deep Blue, with all its prodigious calculating abilities, deliberately play into a drawn position? The only answer is that Deep Blue had also blundered, but was lucky enough to get away with it! That the machine had blundered is indisputable, since even the PC software of the time could detect the draw. One of the machine’s programmers, Murray Campbell, even referred to it as a blunder. One possible explanation is that the well-known horizon effect was responsible. This essentially refers to a situation where the machine stopped calculating right before the crucial bit of information was found.

In any case the match continued with one win for each side, the next 3 games resulting in draws.

Going into the final game, most people wanted Kasparov to win. Some no doubt saw the match as a sort of science fiction struggle between man and machine, and felt their species threatened. But as I indicated above, for a chess computer to outplay the world champion would also be a triumph for humanity – the brilliant researchers and software engineers who designed and built the computer and its software.

Game 6 began with Kasparov playing the Caro-Kann against Deep Blue’s 1. e4. But on the seventh move the unthinkable happened. Kasparov made an elementary blunder, choosing the wrong move order and falling into a known trap. His position quickly deteriorated and he was forced to resign just 12 moves later.

IBM’s Deep Blue had defeated Garry Kasparov, the greatest chess player who ever graced this sorrowful earth. You can imagine the impact of this result. Pundits opined, editorials waxed eloquent, and experts expounded.

IBM, not surprisingly, had been in the match from the beginning for the marketing advantage of a potential win. IBM’s chairman Louis Gerstner said, “I just think we should look at this as a chess match between the world’s greatest chess player and Garry Kasparov.” This remark was immature, self-serving and ultimately demeaning to his company and their remarkable researchers.

In the previous year when Deep Blue lost to Kasparov, IBM was happy to accept the rematch that they had just won. But now that they had achieved the win, their corporate response was the cowardly one of dismantling the Deep Blue research project, in spite of Kasparov’s desire to continue with future matches, claiming that if Deep Blue were to play regular, competitive chess he would utterly destroy it. IBM gave every appearance of fearing just that.

So what is the real story behind this story? In an interview after game 4 while the match was still even, Kasparov said of Deep Blue that “It can only win because of human weakness. In fact, if you look at the match it hasn’t won a single game. I resigned game 2, but the position was drawn.”

Kasparov was prescient for he spoke the truth. Deep Blue’s victory is attributable to human weakness because both of Kasparov’s losses were due to blunders, and Deep Blue did not outplay him. Even in the end games of Garry Kasparov, the outcome of this vast abyss that we call chess is almost always decided by human error, not by human genius.

For additional information:

There is a brief documentary video of the Kasparov vs. Deep Blue match that you can see by clicking here.

IBM still has their website that was created for this match. You can see their Deep Blue project team and read additional background information by clicking here.

If you are interested in learning more about how chess programs work, I have written two blogs that explain the basics and which do not require any previous knowledge of computer software. Just click on these titles to read How Your Chess Program Defeats You, Part 1 and How Your Chess Program Defeats You, Part 2.