Winner's POV Chapter 10: London 1862 Handicap

In Winner's POV, we take a look at tournaments from the 19th century and see the games that allowed the top player to prevail. Some tournaments will be known and famous, others will be more obscure - in a time period where competition is scarce, I believe there is some value in digging for hidden gems in the form of smaller, less known events.

Chapter 10: London 1862 Handicap

Handicap chess (or odds chess) is a game of chess where one player gives the other player some sort of handicap, often in the form of material. At his peak, André Danican Philidor was capable of giving odds of a pawn to practically every known chess master in Europe - that is, he would play as White and remove his f2 pawn, and still have a positive record against everyone he played. Returning to the mid-1800s, with chess clubs growing more popular and populated, odds chess was quite a popular means by which players of various skill levels could play together on relatively even terms. The games themselves were usually quite nice, with the stronger player having to conjure up attacks in order to outrun their material deficit, while weaker players could show off good technique in both defense and conversion.

Handicap chess was quite actively included in the London 1862 congress. Of course, with all of the chess being played, quite a few casual games were played with various levels of odds being given. Adolf Anderssen gave a 10-board simultaneous exhibition where he played without his c3-Knight (unlike Louis Paulsen and Joseph Blackburne, he was not blindfold), as well when his tournament was finished, he played many simultaneous games at the same odds under more casual arrangements. The most important appearance of handicap chess, in my opinion, was this tournament, considered to be the second big event at the congress.

Format, Prizes and Players

I'm going to do this section a little differently than I have in previous chapters, since the format of the tournament is most easily grouped in with the player lists, as you'll see shortly.

Firstly: the tournament was a 24-man knockout, the last knockout on the list for quite some time (I think). Each mini-match was a first-to-two system, with prizes for the top six to be decided in a pool format similar to that of the Ries Divan 1849 tournament (see here). I'll talk more about it when we get there.

The prizes are, once again, nicely laid out in the book for us:

£60 in 1862 is apparently worth about £8100 today, which is a really good payout for an event which people of all skill levels could enter and have a half-decent shot at winning.

Finally, the players. You'll notice that they're presented slightly differently than before:

In addition to laying out the players, this tournament also used a class system to determine appropriate handicaps. I don't like the way they talk about it, so I'll try to make it clearer:

The players were divided into five classes, which we'll label 1-5 - Anderssen was alone in class 1, Blackburne was in class 2 with Ernst Falkbeer, Frederick Deacon and George Webb Medley, and so on from there. Better players were placed in higher classes, with the organizing committee dividing them as best they could.

Odds were given in a manner that was consistent with the difference between the classes of the two players:

If you played someone in your own class, there were no odds.

If you played someone in the class above you, you received move odds (you played White in every game).

Two classes above you, you received pawn-and-move odds (you played White every game, and the opponent removed their f7-pawn).

Three classes above you, you received pawn-and-two-move odds (you played White, your opponent removed their f7-pawn, and you started with your e-pawn on e4).

Four classes above you, and you received Knight odds (you played Black in every game, but your opponent - who could only be Anderssen - removed their c3-Knight).

Interestingly, the player we'll be following only played one match at proper odds, but we'll cover that when we get there.

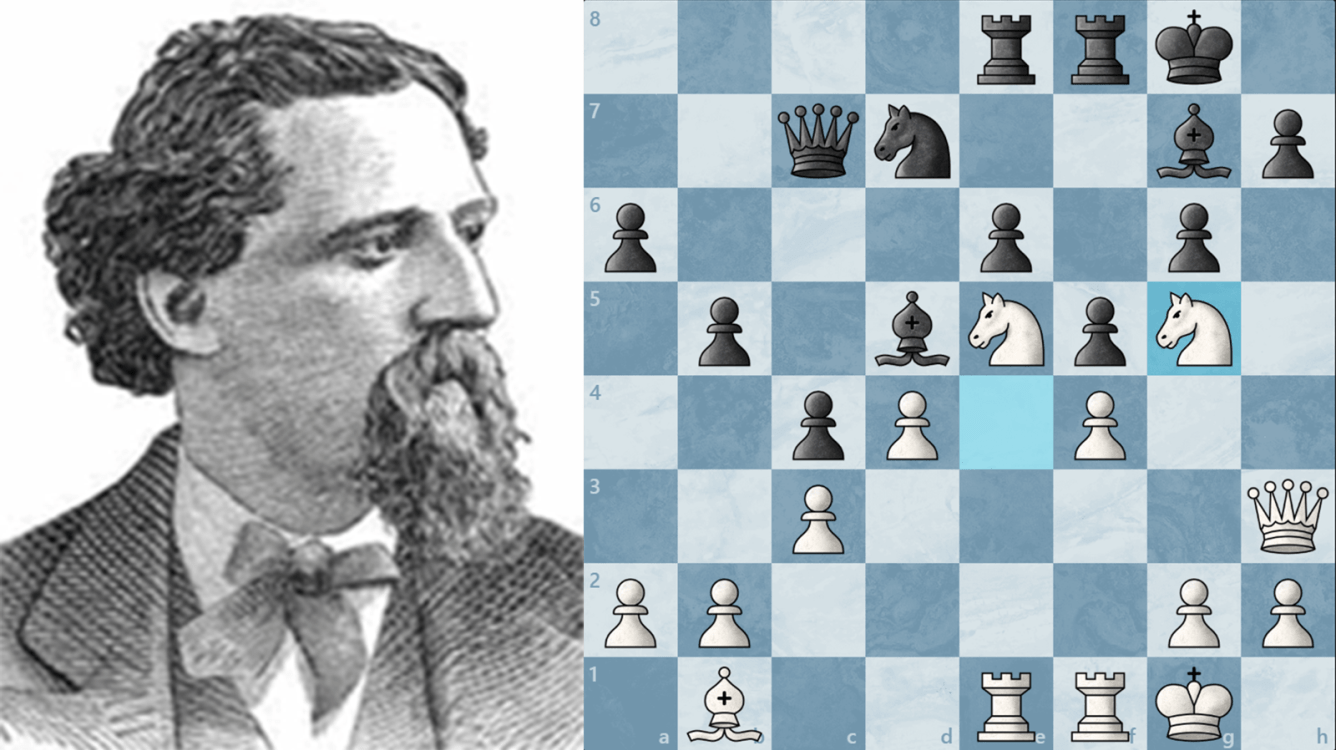

The Winner: George Henry Mackenzie

The Scottish-born Mackenzie, placed in class 3, would be the winner of this handicap tournament. In 1863 he would emigrate to America, and thus we won't see him again until the return of the American Chess Congress, which would be in 1871. Until then, we have to talk about his successes at this tournament, so let us look at the London 1862 Handicap Tournament from the Winner's POV.

Round 1: vs. George Webb Medley

The last time we saw Medley was at the aforementioned Ries Divan 1849 tournament, where he took 2nd place after losing his pool game against Henry Thomas Buckle (and later defeating his brother John Racker Medley in the 2nd place playoff). During this congress, Medley was the Honorary Secretary of the British Chess Association, a member of the Managing Committee for the congress, and a member of the sub-committee formed specifically for forming classes for this event - a busy man, I'm sure. Since he was in class 2, he would give move odds to Mackenzie, sitting behind the Black pieces for the entirety of the match.

In a Petroff, Medley pushed an early f5, which wasn't inherently bad although it did leave his King a little weak. It became a serious problem after he incorrectly sacrificed the b7-pawn, giving Mackenzie multiple pins and potential discoveries that made his life difficult. Mackenzie easily defended the Kingside attack that tried to form from Medley pushing his f-pawn, and once he was up a piece, Mackenzie solidified and took the first game.

In a symmetrical French, Mackenzie was a little too carefree with his 9th move, allowing Medley to immediately equalize with 9... Ne4. The position developed into something extremely ugly, with Mackenzie's Kingside pieces being cramped and his c-pawns being doubled with Medley's Knight on c4. It was Mackenzie's turn to try a Kingside attack, but once it was deflected, his position crumbled, and Medley tied the score with one game left to play.

Medley changed the opening again for the 3rd game, using the Modern Defense with a double fianchetto setup. Just like in the 1st game, he pushed his f-pawn and exposed his King, with Mackenzie exploiting it and tactically crushing the Honorable Secretary. It's a pretty brutally quick game, there's not much to talk about.

Round 2: vs. Alfred Cole

Not only do I know nothing about this person's chess, I don't actually know for sure what their first name is. Ron Edwards at Edo writes "Forster gives his name as 'Cole, A[lfred] J.', so perhaps the first name is not certain." What I do know is that Cole was in class 4 (so Mackenzie played Black in every game in their match) and he defeated David Salter 2-0 in round 1 on even terms.

Against Cole's Ruy Lopez, Mackenzie opted for Morphy's Defense, and Cole eventually traded on c6. Mackenzie made the strange decision to push f5 with Cole's pawn on e5, making it passed and preventing Mackenzie from having a way to open the position to use his Bishop pair. Still, it was solid enough that he didn't have any problems, yet.

As the game progressed, it was clear that Mackenzie was the better player, as he actively advanced his position and put Cole on the defensive. Mackenzie was more tactically aware, winning the exchange before advancing on the Queenside and obtaining a majority on that side. He was playing a slow, steady positional game - a good one at that - and was advancing towards a win.

Cole, however, had a couple passed pawns of his own, and used them to generate counter-chances. The position was very tricky to play accurately, and as Cole traded Queenside pawns and threw his own up the board, it was certainly possible that he could escape. The ending to the game was... well, take a look.

The second game was wildly different. Cole's approach to the Petroff was a weird one, though after Mackenzie's 10... Bf5, Cole was allowed to push his Kingside pawns for a proper Romantic-era attack (and he was correct to do so). The pawns quickly rushed up the board, and Cole had the potential to score a tangible advantage if he was accurate with his play.

The problem with pushing pawns to attack the King, however, is that it leaves your own King vulnerable, which makes things tricky. Cole chose the incorrect path forward, leaving Mackenzie in position to once again take a powerful tactical shot. The exchange was once again won, and with Cole's King out in the open, the game wrapped up quickly. Despite the match ending 2-0, it was quite close, with very back-and-forth games both times.

Mackenzie was now assured a prize, though the exact amount was yet to be determined.

Round 3: vs. S. Solomons

With a tournament that is open to everyone (and where entering is encouraged, given the handicap system), we run into the problem of having many people with little recorded history. Solomons is the second such example (after Cole), though here I don't even know his first name. Solomons was in class 4 (so Mackenzie would again play Black in every game), he defeated Blackburne 2-1 in round 1 - receiving pawn-and-move odds - and James Wilson 2-1 in round 2 on even terms.

Solomons played the English almost exclusively at this tournament, including the games in this match. This was probably one of the least successful showings, however, after Solomons's incorrect thrust of g4 opened him up to a plethora of tactics. The game was a complete blowout, arguably much longer than it needed to be.

The second game looked like something Marmaduke Wyvill would have enjoyed playing at the first London tournament in 1851. Like in the first round, Mackenzie got a little lazy in the opening, with his 12... Bb8 allowing Solomons to make trades that put a lot of pressure on the Black position. After Mackenzie failed to accurately defend, Solomons delivered the second blowout of the match, albeit for the other player. The third game could literally go either way, given these demonstrations.

The third game featured a novelty on move 3, which I'm almost certain is the earliest novelty we've ever seen on this series. It amounted to less than nothing, as Solomons was soon worse after his Ng5 idea left that Knight sidelined. With Mackenzie expanding and pressuring the center, Solomons was forced to look for activity on the Kingside, which he did - although his calculation skills ultimately weren't up to snuff. A chaotic match overall, but this game went in favour of the Irishman.

Mackenzie had thus reached the final 3, where each player had to play a match against the other to determine the top 3 spots (an identical method was used to determine 4th-6th).

Round 4.1: vs. Adolf Anderssen

Enter the man of the hour. Anderssen was an extremely busy man during this congress, as the many events he took part in should indicate. As the only person in class 1, he was the only one ever required to give odds of a Knight, which he did in his first two rounds - 2-0 vs. Charles Pearson and 2-1 vs F. Lamb in rounds 1 and 2 respectively. Round 3 pit him against Valentine Green where he won 2-0 giving odds of pawn-and-move, the same odds he was required to give Mackenzie.

Now, I'm going to be honest: the games played in this match were rather awkward to write notes for. To put it simply, Anderssen was never able to overcome the odds he offered, getting beaten quickly and soundly in both games. I can imagine he was quite exhausted with chess at this point, as after playing this match, he defaulted the other in the pool and claimed to be content with the metaphorical bronze medal. Feel free to look over the games and see if you can explain things better than I.

Round 4.2: vs. Frederick Deacon

With Anderssen defaulting, the match for the top two spots was thus to be played between Mackenzie and Deacon (who, funny enough, had dropped out of the main tournament to focus on the handicap - it was clearly a good decision). Deacon's path to the final was as follows: 2-1 vs. Lord Cremorne (giving move odds), +2-0=3 vs. S. J. Green (giving odds of pawn-and-two-moves) and +2-0=2 vs James Hannah (giving move odds). Deacon was in class 2, so he would once again give move odds, this time to Mackenzie.

Deacon tried the Scandinavian Defense for the first game (known as the Centre Counter-Gambit at the time), with an early f5 that attempted to upset the balance of the position for both players. The e6-pawn was left weak as a result, and Mackenzie pressured it strongly. Mackenzie eventually stabbed a thorn of a pawn on e5, leaving Deacon with a near permanent space disadvantage.

Deacon had drawn a lot, and this game helped show why: he could play incredibly solidly when needed. Despite Mackenzie being clearly better, he wasn't able to find a way to turn his advantage into something tangible. Pieces soon came flying off the board, and a draw was agreed to with only Queens and pawns remaining.

Deacon fired off the Hyperaccelerated Dragon for this game, managing to fianchetto both Bishops without compromising his position. He actually showed a better understanding of the position, expanding rapidly on the Queenside and picking off Mackenzie's Bishop pair. Mackenzie, in turn, shifted his Knights and Queen over to the Kingside to try an assault on the Black King.

Mackenzie's attack left both Kings somewhat exposed, and the position became incredibly complex. The tournament book was calling out blunders every other move, the engine highlighting them more often still; the complexities of the position were enormous, and all three results were possible. As it stood, the endgame should have been better for Mackenzie, his Queen well-placed to trump the Bishop and Rook of Deacon.

As was often the case, the endgame could have been played better. Deacon was allowed to get his King into the position, and with Mackenzie's permission, it aided the rest of his pieces in delivering a perpetual check. I think this is my favourite game in the entire tournament (hence the thumbnail), and so I really recommend you look it over, as this synopsis and my notes probably don't do it enough justice.

Deacon essayed the Hyperaccelerated Dragon once again, and once again it paid off. The players chose a series of moves that gave Mackenzie more central space, in exchange for Deacon getting an open f-file for his Rook - this file turned out to be quite important. After Mackenzie incorrectly pushed 18. h4, Deacon fired off an exchange sacrifice on f3, gaining a bunch of pawns in the process. He had an additional three pawns by the time the tactical flurry was over, and had the means to push for a win.

Unfortunately for him, 25... Qc4 was just a horrid blunder that cause him to drop a piece. Once he was down a Rook for three pawns, it was obvious he had nothing, and Mackenzie methodically gobbled them all up before forcing resignation. I can only imagine the relief Mackenzie felt after this game, having been better in the previous two and being in a lot of trouble for this one. Only one more game to go.

The fires were lit, and Mackenzie kept his momentum with an aggressive line of the Giuoco Piano where he sacrificed a pawn to push f4. The position was opened up, and Deacon was very politely asked (coerced) to castle Queenside, confirming the game would be an attacking one. He made something of an attack on Mackenzie's King, but it was a simple checkmate threat that was easily swept aside. Once it was over, Mackenzie took his turn attacking.

The tournament book didn't believe in the attack for quite some time, but Mackenzie played it quite nicely. The major pieces were the major players, ripping open Deacon's position from checkpoints secured by his pawns. I feel it best to just let you enjoy the attack, as it was good enough to win Mackenzie the tournament, crowning him as one of the major winners at the London 1862 congress.

Conclusion

While far from the most prestigious victory of Mackenzie's career, this tournament was still the first in the long list of victories which he constructed. It wouldn't be until 1878 when he would play another major tournament in Europe, however after moving to America in 1863, he would be quite active there - as I said, we'll get to that later.

After the London 1862 congress, there would be a few years before the next major tournament, though British chess would be more alive than ever. Wilhelm Steinitz would officially move to England after defeating Serafino Dubois +5-3=2 in a match shortly after the congress, and he would be a big player in European chess moving forward. He'll be talked about a little more in the next chapter, so stay tuned.

Chapter 5 (contains links to chapters 1-4)