Winner's POV Chapter 16: London 1872

In Winner's POV, we take a look at tournaments from the 19th century and see the games that allowed the top player to prevail. Some tournaments will be known and famous, others will be more obscure - in a time period where competition is scarce, I believe there is some value in digging for hidden gems in the form of smaller, less known events.

Chapter 16: London 1872

I previously mentioned that I wasn't going to do a post on this tournament, since there are missing games and it's relatively small. However, I've been fortunate enough to have one tournament for every year since 1867 (although I did use one tournament that spanned 1868-1869 so you can call me a cheater if you want) and I'm not ready to break that streak yet. However, the only other tournament in 1872 that I think deserves to be a part of this series is also quite small. Thus, we're giving the British Chess Association one more chapter, and only one more chapter (at least for the next decade, I haven't planned past that).

Format and Prizes

Single round robin, with drawn games still being replayed. Why they decided to keep this rule of replaying drawn games is beyond me, but here we are.

Adding to my frustration, I can't find any mention of a prize fund. There is no tournament book for this event; my primary source has been The Westminster Papers, the monthly report for the hosting Westminster Club, and they never mention anything about prizes. They do bring up the time control, 15 moves per hour, and that about covers everything I know about the tournament logistics.

Players

First, "Hiber" was the pseudonym used by George Alcock MacDonnell, for reasons I've been unable to determine. Second, this was the international debut of Johannes Zukertort. Zukertort was the student of Adolf Anderssen, and after he beat his teacher in an 1871 match (+5-2) he began travelling to other international tournaments in Europe. Last, the games against George Hatfeild Gossip and William Martin are lost to me; it's these games that were the reason why I was hesitant to include this tournament, but seeing as there are five other strong masters, I think they more than make up for the loss.

The 1871 Edo lists give us starting ranks of Wilhelm Steinitz (1st), Zukertort (7th), Joseph Henry Blackburne (8th), Cecil de Vere (11th), John Wisker (14th) and MacDonnell (16th).

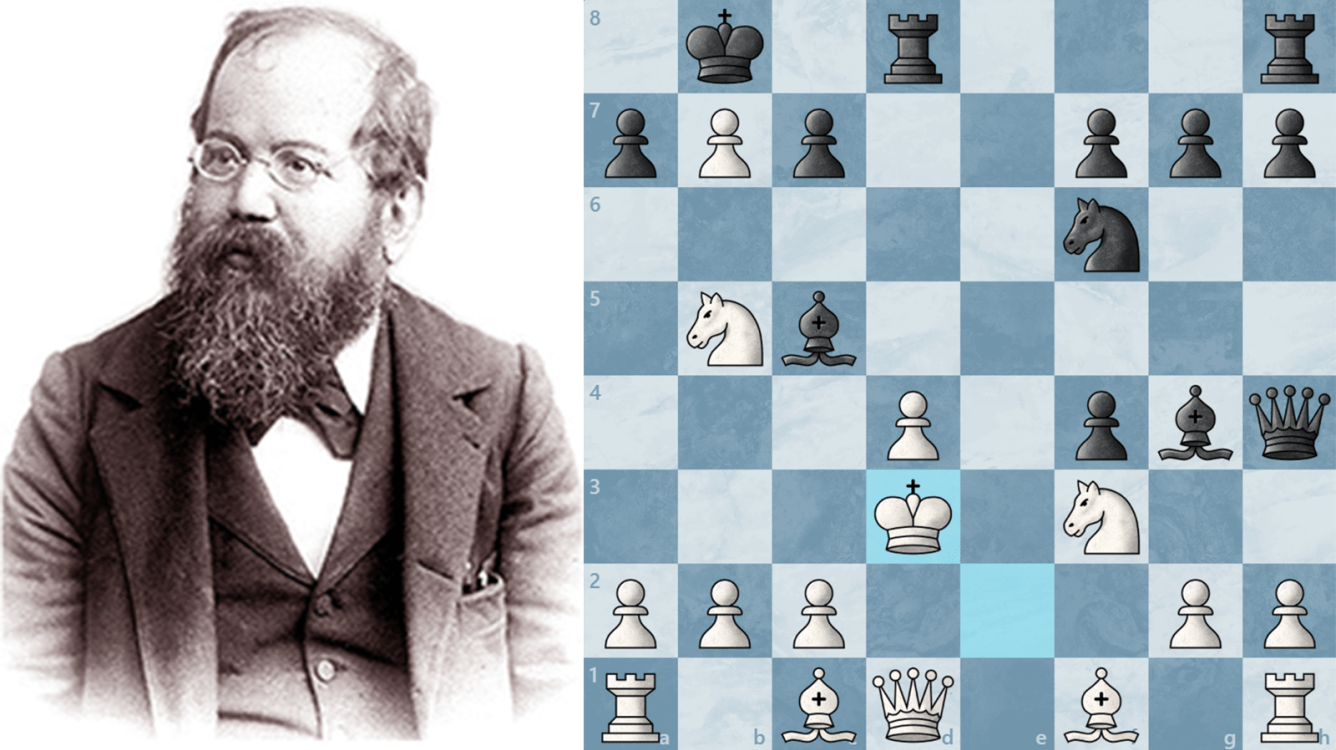

The Winner: Wilhelm Steinitz

At last, Steinitz had a proper international tournament victory under his belt. Despite being considered the world's strongest player since 1866, we've gone through three tournaments since then which he failed to win. However, none of the winners of those three tournaments took part in London 1872, so Steinitz was able to capitalize on a most golden opportunity. As we applaud the first World Champion's flagship appearance in this series, let's look at the London 1872 tournament from the Winner's POV.

(Note that, due to a lack of schedule and missing games, I won't be bothering with rounds for this one.)

vs. Cecil de Vere

Now, more than ever, I really wish I could have devoted a chapter to de Vere's win in the 1866 Challenge Cup. The first official British Champion has been getting tossed around like a ragdoll in almost all of his appearances, and unfortunately, this story does not have a happy ending. De Vere developed tuberculosis in the late 1860s, and became an alcoholic in 1872. While his performance in the Challenge Cup was impressive (=1st, then lost the playoff against Wisker), his performance in this game left something to be desired.

vs. John Wisker

As previously mentioned, Wisker won the 4th Challenge Cup at this 1872 congress, which probably took more of his attention than did this tournament. As this is the last time we'll be seeing Mr. Wisker, I should mention an unfortunate coincidence: he was also diagnosed with tuberculosis, around 1876. He emigrated to Australia that year, and while he still played chess, he would never again enter a major tournament.

Wisker's English was played strangely, and Steinitz efficiently capitalized on his opponent's many Queen moves and gaping hole on d3. The Austrian's Knights and pawns planted themselves firmly in the White camp, depriving Wisker of castling rights and cramping his position. However, he was able to sacrifice his Bishop pair in exchange for getting to safely push d4 and improve his center, allowing him to survive the opening.

Wisker made a good judgment call as he began getting active on the Kingside, needing to drum up an attack to compensate for his inferior position. However, Steinitz had mentioned that he took great inspiration from Louis Paulsen, arguably the greatest defensive player of the past decade or so. Steinitz was extremely hard to attack, and Wisker wasn't precise enough to see it through.

vs. Johannes Zukertort

In his first trip to England, Zukertort had a very busy schedule with Steinitz in particular. Outside of this tournament, they met in the handicap tournament, where Zukertort won their individual matchup (+1=2) to knock Steinitz out. Additionally, they played a match after the congress had ended, which Zukertort lost badly (+1-7=4). Still, this early in this career, getting to play so frequently against the strongest player in the world is exceptional.

Steinitz broke out his namesake opening in the Vienna Gambit, to which Zukertort replied with the Zukertort Defense (as you do). Steinitz went on one of his famous King walks, with his King going up to c3 by move 11. Zukertort sacrificed a piece to try and deliver checkmate, but as usual, Steinitz's defensive abilities were up to the task. Once the Queens were traded, Steinitz had a rather straightforward road to converting the game.

vs. George MacDonnell

"Hiber" was partially to blame, in my opinion, for why this tournament received such a small amount of press, due to him drawing out his games long after the tournament had been declared in Steinitz's favour. I don't know what else was going on, but his relatively poor showing in the Challenge Cup (4/7) was possibly to blame.

MacDonnell played a beautiful opening in the King's Gambit Declined, throwing out a temporary piece sacrifice that turned into a permanent pawn sacrifice. His Rooks were doubled on the open e-file, and it took Steinitz quite some time to alleviate the pressure. This was doubtlessly the most someone had challenged Steinitz in the opening.

When Steinitz offered a trade into an endgame, MacDonnell traded in the wrong order, not giving nearly enough respect to Steinitz's passed e-pawn. However, that ended up being the lesser of two problems, as Steinitz was able to attack the King along the f-file with his Rook instead. A strong win for Steinitz, who was able to show his resilience and resourcefulness better in this game than in all of the others.

vs. Joseph Blackburne

The rivalry these two had in the early phase of their careers deserves some attention. At the London 1862 tournament, less than two years after Blackburne had first learned chess, he ground down Steinitz in a 70-move endgame. Blackburne would be one of the first to play Steinitz in a match after the latter permanently moved to London, which Steinitz convincingly won (+7-1=2). However, the tournament games had still gone Blackburne's way, as he won their game at Dundee 1867 and scored 1.5/2 at Baden Baden 1870. Would that trend continue?

Blackburne opted for the Evans Gambit, which he had used at Baden Baden to get a comfortable draw with White (after winning with Black the day before). Steinitz used the Compromised Defense, giving Blackburne a golden opportunity to fight his way into shared first (he had only lost one game, to de Vere). While Steinitz had his two extra pawns, it was hard to say that Blackburne's pieces weren't looking dangerous.

Steinitz was the first one to go seriously wrong, as his means of forcing a trade of light square Bishops left his Knight sidelined, and gave Blackburne a crucial chance to attack the Black King. Had he pushed 23. h4, we may have seen a completely different game - and overall tournament - result. Blackburne's 23. Qf5 was much slower, and gave Steinitz enough time to mobilize his forces. While Blackburne did his best to make something happen in the endgame, there was no stopping Steinitz at this tournament.

Following this loss, Blackburne promised to never play the Evans Gambit against Steinitz again, a promise he held for the rest of Steinitz's life. We'll continue this rivalry in chapter 18, for anyone who enjoys this as much as I do.

Conclusion:

While not significant in itself, Steinitz could finally say that he had won an international tournament, and a 7/7 score would certainly help solidify his position as the world's #1. With the Austro-Hungarian Empire set to host the next World's Fair in 1873, a chess tournament was sure to follow, for which Steinitz would certainly travel. I have one more topic I'd like to discuss before then (in the following chapter), but there will be lots to discuss when we get to Vienna.

Chapter 15 (contains links to chapters 11-14)

Chapter 10 (contains links to chapters 6-9)

Chapter 5 (contains links to chapters 1-4)