Winner's POV Chapter 21: Fourth American Chess Congress (Philadelphia 1876)

In Winner's POV, we take a look at tournaments from the 19th century and see the games that allowed the top player to prevail. Some tournaments will be known and famous, others will be more obscure - in a time period where competition is scarce, I believe there is some value in digging for hidden gems in the form of smaller, less known events.

Chapter 21: Fourth American Chess Congress (Philadelphia 1876)

With 1876 marking the American Centennial, it was a busy time on this side of the Atlantic, and the chess world was no different. I found three "major" American tournaments held in this year (I put quotes on major as they were all American-only tournaments, but all of them featured most of the best American players), with two in New York and the third in Philadelphia. Of the New York tournaments, there was the Cafe International tournament held at the start of the year, which was won by American Champion George Henry Mackenzie; in autumn, there was also the Clipper tournament, won by breakout star James Mason (Mackenzie didn't compete). The tournament we'll be focusing on today is, in most regards, the most important of the three.

The Fourth American Chess Congress was initially meant to be an international tournament, as was tradition for countries hosting a World's Fair - America did indeed host it's first World's Fair this year, dubbed the "International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures, and Products of the Soil and Mine." However, due to the longer than average trip required by European masters, extra funding would be required, which failed to happen due to two chief concerns: a relative lack of funding provided by the New York chess clubs (for reference, Philadelphia contributed $370, St. Louis $185 and Boston $103.50; New York sent only $30, of which $20 was just Mason's entry fee), and an insistence on publishing a tournament book. That second one especially irks me, partly for the reasons I discussed in the previous ACC chapter (see here), partly because the man put in charge of annotations, William Henry Sayen, was not a good player; many times when reading his analysis, the resulting position was not at all how he evaluated it, with him sometimes dropping a full piece at the end. 19th century America, you're frustrating, stop it.

In spite of the above, there were some successes as a national tournament. The governor of Arkansas, Augustus Garland, provided a silver cup to be used as part of the first prize. As well, in spite of the above issues, over $1000 was raised, providing a prize fund of around $800, finally surpassing that of the 1857 ACC. America was not yet as successful a chess nation as the European countries we've previously featured, but they were getting closer and closer.

Format and Prizes

The format was a double round robin, with draws not needing to be replayed. The time control was 12 moves per hour, slower than most European tournaments, and even slower than the previous ACC.

The book of the Fifth American Chess Congress is again the neatest source for the prizes:

The prizes are split across two pages, hence the two screenshots. In any case, $300 in 1876 is apparently equivalent to about $8500 today, which is the second most lucrative prize in ACC history, surpassed only by the first ACC (though that had less sizeable prizes for everyone below first).

Players

Notably absent was George Mackenzie, however he was the only one to provide money from New York (aside from James Mason's entry fee), so he still participated in a way. As well, Dion Martinez played four games before withdrawing from the tournament, owing to a family issue that sent him back to his home country of Cuba. With that in mind, the 1875 Edo list puts the top of the field as Mason (13th), Max Judd (18th) and Henry Bird (20th).

The Winner: James Mason

The tournament book claims that Mason's reputation was worldwide, and there is some evidence to support that; the Westminster Papers, despite not having access to the games, did note on their coverage that they expected Mason to win with Mackenzie not entering. His successes thus far have been in matches against American players (which I'll touch on as the respective opponents come up), as well as some large tournaments for American amateurs that are sparsely documented. Regardless of his history, James Mason would go on to receive invites to many European tournaments after this, so it's a good thing we're going over his debut of sorts. With that, it's time to look at the Fourth American Chess Congress from the Winner's POV.

Round 1: vs. Henry Bird

Once again, I'm using "round" very liberally, as players were allowed to play their matches with relative freedom. All of the games are dated, with this game being the first in the entire tournament book, so I'll once again be using "round" to mean "the order in which the games were played."

Henry Bird's work often brought him to America, so this trip wasn't unprecedented; his historic 1866 match against Wilhelm Steinitz was interrupted by Bird having to travel away from England. He participated in all three of the aforementioned tournaments, finishing in third place in each. Outside of that, he had a very developed rivalry against Mason, who won their formal match (+11-4=4), but Bird claimed that he won the majority of their games if offhand games were included (Bird mentioned a 27-20 overall score, meaning he scored 21/28 in offhand games). This was likely one of the most anticipated matchups of the tournament, so it's something of a shame it occurred right at the start.

The first game is regarded as the best game of the tournament by contemporary sources. It featured Bird playing his very own Bird opening, which worked quite nicely, as he ended up with more central space and forced Mason to defend a backwards d-pawn. Mason counterattacked on the g-file, and the players played a long, tense game. It was a good defensive showing from Mason, who never caved in to Bird's pressure.

At move 49, Mason offered a draw, which was declined. This proved to be a mistake, as Bird allowed the game to transition into a Queen endgame where Mason had chances to win. Queen endgames are among the most complicated in chess, and unfortunately for Bird, he wasn't able to correctly navigate the waters. Resignation occurred on the 98th move, which may mark the longest game of the series (don't quote me on that).

Not intent on easing up, Mason threw forth the King's Gambit in the return game, opting for the Paulsen Attack. Although Bird's long career left him very well acquainted with the King's Gambit, his play was shaky, and he definitely was on the worse side of equality when the pawn was given back. Although his position had no weaknesses, Mason had all the activity, and he applied not-insignificant Kingside pressure shortly after.

Ultimately, the game fizzled out to a draw after Mason offered a Queen trade. Although he had shown himself to be a strong endgame player, the opposite-colour Bishops made things easy for Bird once he traded off all the Rooks. While both players could've had more, given that their previous game lasted 12 hours, I think a hard-earned draw is a natural result.

Round 2: vs. Lorenzo Barbour

The tournament book describes Barbour as a player "whose reputation is well known over the country for great originality," however I've not found enough games from before this tournament to make any conclusions like that. I have found a handful of reports that say he was a very lively and energetic fellow, so perhaps that carried over to his play. There's only one way to find out.

This first game was another struggle that lasted over 90 moves, which is part of the reason this took so long to write. Philidor would be happy to know that the pawns were still the soul of this chess game, as Mason's pawn play was subpar. Both his c- and a-pawns were weakened as he pushed them, and as a result, Barbour won the latter and created a passed pawn next to the former. For someone whose play was praised as being brilliant and original, this looked like it was just going to be a positional grind.

If you were to put Capablanca behind the White pieces, the point would've been converted quickly and effortlessly. Unfortunately for Barbour, he was many years ahead of Capablanca in all the wrong ways. After a struggle lasting over 80 moves, he blundered into a stalemate trick, and the game was drawn. Barbour would accidentally draw another winning endgame later in the tournament, so this isn't an isolated incident. Still, a miraculous save for Mason, who remains undefeated despite two close calls with Black.

The second game was much more straightforward. After Barbour played his own weak pawn moves and refused to castle, Mason found a sham piece sacrificed that facilitated the center being blown open. Barbour's King was walked out into the open, and resignation was quickly forced before one of the monarchs was lost.

Round 3: vs. Albert Roberts

Roberts was 19 at the time of this event, with his only competitive experience being some games he played against Mackenzie and Bird earlier in the year. I could only find one game of his outside of this tournament, which was indeed a win against Bird earlier in the year. Bird won both of their games at this event, however, so it remains to be seen just how far along in his chess development Robert was. However, given that I found no games from him after this event, I suppose it's not worth talking about.

Mason switched up his opening for this game, opting for the Wormald Attack in the Spanish. He didn't abandon his attacking nature, however, as he doubled the pawns in front of Roberts's King at the first opportunity. Although he won the pawn on f6, Mason wasn't able to find a knockout blow, and Roberts found an active defense with his heavy pieces and Bishops while trying to open up the center. It was a rather complex first 20 moves.

Roberts didn't quite have the full board awareness necessary to properly conduct the last few moves. While his final Be7 idea did nicely defend another one of his pawns for a time, he played it at an inappropriate point, and the resulting tactical flurry lost him an exchange as well.

The second game is rather bereft of drama. Although Mason's pawn play again lead to potential issues, they never properly manifested. Roberts captured in the wrong order on move 15, and the resulting exchanges lead to the pieces being erased from the board with maximum efficiency. I'm sure a quick draw wouldn't be a disappointing result for Mason, who was likely in a comfortable spot atop the standings right now.

Round 4: vs. Jacob Elson

Elson was a member of the organizing committee for this tournament, along with Barbour and Sayen (the annotator I dislike). He actually provided his own annotations for his games, which were usually more accurate. The tournament book claims that his reputation is well known even in Europe, though I've not found any noteworthy games from him up to this point; he would play a handful of games against Steinitz in the early 1880s, but obviously we're not there yet so I'm not sure what to make of this.

This first game followed one of Blackburne's games from the London tournament earlier in the year, though I doubt either of these two read the Westminster Papers so it's likely just a coincidence. The game could've been ended very quickly if Elson had spotted a Bishop sacrifice on h3, but he didn't, and instead played quite passively. If you've been following along attentively, you'd know that Mason is a very proficient attacker, which he demonstrated once again here. It's a nice game, with the lowlight definitely being Sayen's commentary (I make note of the most egregious mistake in my notes for move 13, if you'd like the best example).

The return game featured quite a pleasant surprise for Elson, as Mason just dropped a pawn through his 8th move. I think his nerves were quite strained during this game, because the next sequence of moves resulted in trades that served to further improve Elson's position. The computer gives +5 as early as move 16, which is pretty rare to see against the top dog in the event.

As the game progressed, it became clear that Elson was probably respecting Mason too much. Although he got his Rooks doubled on the open e-file and managed to make a passed d-pawn, he didn't do much to utilize these assets. He traded a pair of Rooks, and then the Queens, and the resulting opposite-colour Bishop endgame was a lot harder to win. It was certainly possible, but the players drew shortly after the Queens came off. Yet again, Mason survives a game he had no business salvaging. If this were the World Cup, he'd advance on to round 5 after winning four mini-matches.

Round 5: vs. Harry Davidson

Davidson was the youngest player in the field at 18, so the above picture isn't accurate yet (it appeared in a 1905 publication). The tournament book describes him as "probably the most brilliant player in the country, the youngest contestant, of indomitable pluck and daring style." Let's see if he lives up to that great praise.

For this King's Gambit, Mason broke out the extremely weird 4. Qe2, likely as an attempt to get his young opponent "out of book." Davidson accepted the challenge by planting his Knight on g3 and constructing a structure that let him keep the gambit pawn. The pushback clearly was not expected by Mason, who shortly thereafter opened up a gaping hole on e5. As a result, Davidson had a firm grasp on the center, and a passed h-pawn that he was free to push. It was complete domination.

Of course, we know Mason is a resilient defender, and he did try to spice things up with a piece sacrifice on move 24. As the struggle continued, Mason won back multiple pawns and had shortened the gap to something nearly manageable. Unfortunately for him, he was the one who missed a tactic on move 41, as he dropped the exchange and finally had to accept that his position was unsalvageable. A terrific first game for the young player, and the first loss for Mason.

The return game is of very low quality, so I present it without notes. It's on the longer end (although not quite 90 moves), and I'll let you look over it yourself.

Round 6: vs. Preston Ware

We last saw Preston Ware at Cleveland 1871, where he got blown off the board twice by Mackenzie, and finished fifth overall with 9/16. How has he improved his play over the last five years?

The first game started as a Queen's Gambit Declined, but after Ware's f5 thrust, maybe it could be grouped in with the Dutch. Either way, it wasn't very good, as Mason got two separate Knight outposts during the game that exerted a significant amount of pressure. However, there was neither a knockout blow nor a way to transition into a good endgame, so Mason stalled. As the game went on, it seemed that Ware found his footing and equalized.

Despite the endgame being incredibly balanced, Ware actually played on for a little longer. His 31st move apparently took around 90 minutes, and was part of a long sequence that was likely intended to win Mason's Bishop. However, what instead happened was him capturing a pawn at the wrong time and losing his Queen because of it. Oops.

The next game confused me when I first went through it, because a lot of the moves make no sense to me. Ware's 16th move is the best example, since he missed an elementary Knight fork and instead played a2-a3. Somewhat ironically, this game was lost because Mason found a Knight fork, so I'll leave it as-is because that tactic is pretty amusing in context. Also, somewhat surprisingly, this is Mason's first 2-0 of the entire event.

One possible explanation for why the above games are of questionable quality, as I first read from Jeremy Spinrad of ChessCafe.com, is that Ware and Mason were cheating. Ware would later be involved in another cheating scandal at the 5th ACC in 1880, which I'll elaborate on more when we get there, so it's not out of the question. For now, you can check out Spinrad's arguments here.

Round 7: vs. Max Judd

I would have said that Judd was the second strongest active American behind Mackenzie, but Mason's reputation seems to place him ahead of the St. Louis native. The two were actually tied at this point, as Judd had earned more wins, but had lost two games to Bird and Davidson. Everything was to play for in this final match.

The players elected for an Exchange French for this game, choosing a particularly symmetric setup that has a draw rate of over 75%. Judd, probably feeling the need to play for a win with the White pieces, lashed out with 11. f4, which opened a hole that couldn't easily be filled. Mason maneuvered his forces in such a way that he was able to plant a passed pawn on e4, and supported it with f7-f5. He was clearly for choice in the middlegame.

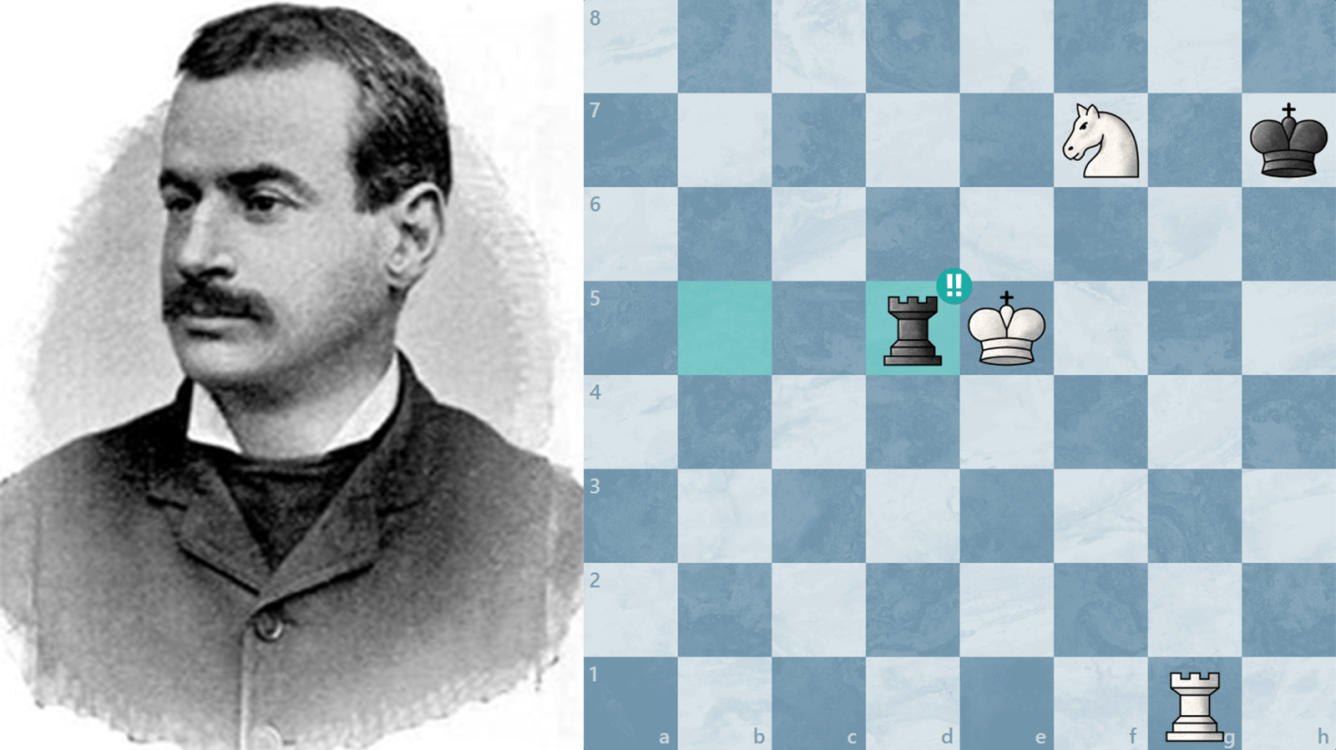

Judd was apparently quite sick at this point in the event, which means that Mason's decision to play a long, grindy game was a practical one. He poked and prodded at Judd's position, especially eyeing down his weak d-pawn. After a long session of maneuvering, the pawn was finally lost, and Mason had a winning Rook endgame that he converted without much drama. That's four consecutive wins for our subject, a good streak to get on at the tail end of the event.

The second game wasn't played, due to the result not affecting any other result and Judd understandably not wanting to play while sick. It was scored as a draw, and the final results were as follows.

Conclusion

For now, James Mason stands atop the American chess scene, though that wouldn't be the case for long. After this event, he would venture to Europe, and would play in international competitions there. In fact, we'll see both him and Mackenzie make their international tournament debut in a couple of chapters, so prepare yourselves for the introduction of America's best to the European chess scene shortly.

Chapter 20 (links to chapters 16-19)

Chapter 15 (links to chapters 11-14)

Chapter 10 (links to chapters 6-9)

Chapter 5 (links to chapters 1-4)