A Century of Chess: Alexander Alekhine (from 1910-19)

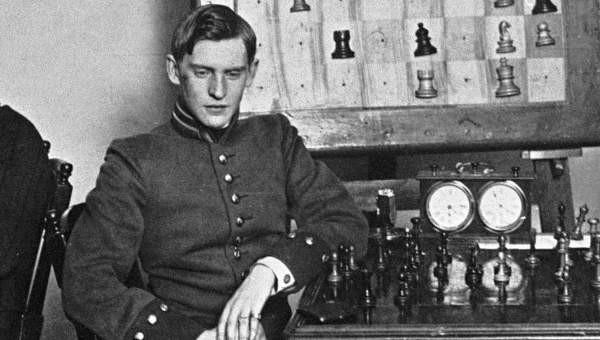

Alexander Alekhine was born in Moscow in 1892 to an aristocratic family. His talent was obvious from an early age. He had the benefit of learning from his brother Alexei, a strong player; avidly played correspondence chess; and had Fyodor Duz-Khotimirski for a tutor. As early as 1908, The British Chess Magazine called him "a portent from Russia."

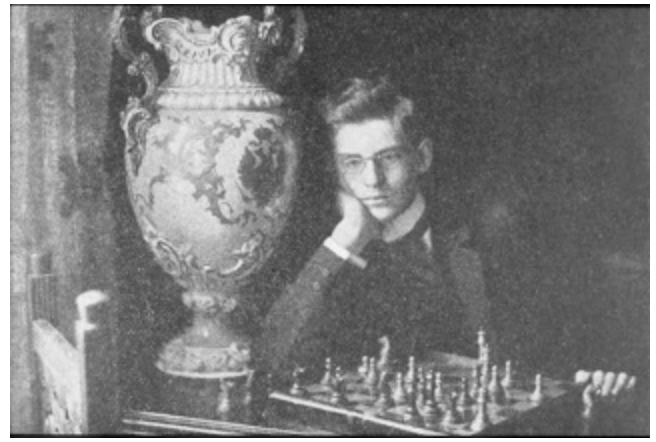

For a while Alekhine’s trajectory followed that of some kind of Russian aristocrat’s — an ornament to the czar’s regime. He was a cadet and then later entered the Imperial Law School for Nobles. In 1909, he had his first major triumph, winning the Amateur Tournament at St Petersburg 1909. The prize was a Sèvres vase, awarded by Tsar Nicholas himself, and, poignantly enough, Alekhine carried the vase around with him for the rest of his life. When he died, completely alone in a hotel room in Portugal in 1946, the vase was in the room with him.

Alekhine was from the beginning notably confident in his chess ability. Pyotr Romanovsky recalled meeting 16-year-old Alekhine and being taken aback when Alekhine announced that he was almost certain to win the Amateur Tournament. "With these gentlemen you must only play boldly," Alekhine declared. His real breakthrough came at the Hamburg 1910 International Tournament where he took shared seventh and played a brilliancy against Leonhardt.

He had some growing pains, but in 1912 he won a tournament at Stockholm, in 1913 he decisively defeated the talented Stefan Levitsky in a match, and won at Scheveningen.

In early 1914, he won against a very large field at the All-Russian Masters and qualified for the St Petersburg International Tournament. As Grigory Levenfish would write, "No one was placing any special hopes on Alekhine, as this was his first opportunity to cross swords with world-class grandmasters," but he played steadily to reach the finals and then outclassed both Tarrasch and Marshall to take third and to make it clear that he was one of the very best in the world.

He was leading at Mannheim, the last tournament before the start of the war, and then went through a series of adventures to return to Russia. He served with the Red Cross during World War I and received three medals for removing the wounded from battle — although, oddly, his wartime exploits have attracted virtually no attention in chess history. He vanished from sight for an extended period during the Civil War (in the West, he was widely believed to have been killed by the Bolsheviks, although as it turns out, he worked as a police inspector, pursued a career in acting, ran afoul of the Cheka) and then surfaced in France in 1921, which was his home for the next decades.

Within this period, the legend of Alekhine starts to compete with, and in some cases, outdistance the actual person. The guiding idea with the Alekhine legend is the absolute single-mindedness of his dedication to chess. As he was fond of saying, "The purpose of a human life and the meaning of happiness is to do the maximum that a person is capable of." At Hamburg 1910, he played in defiance of doctors’ orders — he was supposed to be bedridden with a leg injury, but, receiving a last-minute invitation, he traveled to Hamburg and played the tournament in a wheelchair. His habit of sprucing up his games in post-mortem annotations appears fairly early — a demonstration of how ego and perfectionism were closely intertwined for Alekhine. And, from about 1913, Alekhine’s lifelong rivalry against Capablanca becomes apparent. At the St Petersburg Quadrangular, he lost two games to Capablanca — a clear indication for Alekhine that, talented as he was, he simply wasn’t in Capablanca’s class. Two additional wins by Capablanca against him at St Petersburg 1914 cemented that conviction. At this stage, Alekhine and Capablanca were friends, analyzing and hanging out together, but Alekhine seems, quietly, to have decided that his life’s mission was to overcome Capablanca. As early as 1914, he would write to tournament organizers asking if Capablanca was attending and avoided all tournaments with Capablanca in it — determined to build up his strength before challenging Capablanca again. It was a long road for Alekhine. He wouldn’t score his first win against Capablanca until their 1927 match, by which time he had thoroughly broken down and rebuilt his play, creating a new level of steadiness that he thought was needed to compete with Capablanca.

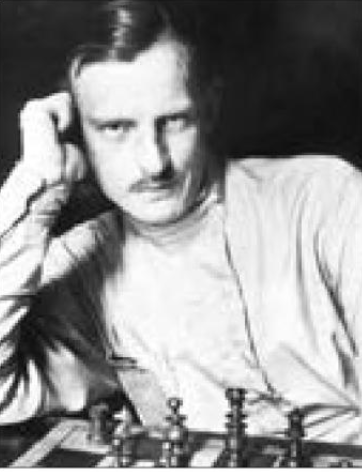

Alekhine's Style

Alekhine is best known for his combinations. “These were gigantic conceptions, full of outrageous and unprecedented ideas,” wrote Bobby Fischer in the 1960s. These conceptions were often a bit mystifying to other players. Fischer believed that "in a sense his whole method of play was a mistake" — i.e. that there was something baroque about it. There was a suspicion (which Alekhine may have shared) that his play could be a bit circus-y — embarking on the wild combinations before having achieved a clear positional superiority. Alekhine himself worried that he had the "dangerous delusion" that no matter how uncomfortable his position became he would always be able to think up some "unexpected combination."

Bogoljubow complained that he could find all of Alekhine’s combinations but had no idea how he achieve the positions that sparked them. And different players had different theories about how Alekhine managed the strategic portion of the game. Breyer wrote that Alekhine orchestrated his openings all around knight outposts — and that he was basically a ‘knight’ player. Fischer thought that he played the opening indifferently and then around move 20 started to scheme up kingside attacks. All I’m really able to say is that Alekhine, more than other players of the era, was willing to complicate from early in the game. He is constantly applying pressure, constantly looking for opportunities to attack or to create some combinatorial flurry. If there were shortcomings in his structures, it really took a top-level player to expose them.

A great deal of what brought Alekhine to top-level was endgame technique — more than anything, that’s what separated him from Nimzowitsch, for example. He had a similar approach to the endgame as Pillsbury or Tarrasch, treating the endgame as an extension of the middlegame, in which sharp, forcing play tended to prevail.

Alekhine in the Opening

Later in his career, Alekhine would remark sorrowfully that we “still know so little of the opening.” More than anyone, he would create the ‘modern’ perspective of the opening, in which opening, middlegame, and ending are fused together, and in which a master’s life is dedicated to the off-the-board discovery of ‘TNs’ — unexpected moves deep in some theoretical line that, typically, give one player the opportunity to seize a long-lasting initiative. In the 1910s, though, Alekhine’s opening play seemed a bit haphazard. He couldn’t quite seem to make up his mind between 1.e4 and 1.d4 and was partial to the Queen Pawn’s Game, which doesn’t really suit him. He did come up with some interesting ideas, though — most notably, the Alekhine-Chatard Attack in the French.

Sources: Of course there's been a great detail written about Alekhine. The most important source is his My Best Games of Chess, which has been an inspiration to countless strong players. There's a great deal of new biographical information in the Linder biography of Alekhine. Levenfish's reminiscences of Alekhine from this period are here and Romanovsky's here.