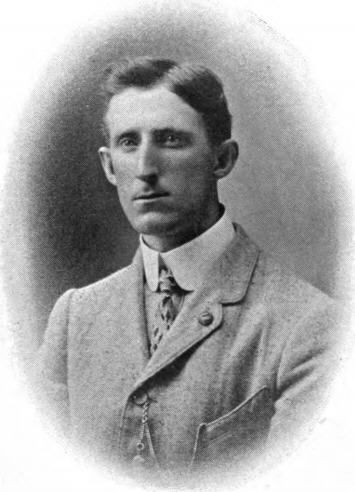

Frank Marshall

Bio

Frank James Marshall (1877-1944) was a brilliant attacking player and the United States chess champion from 1909 to 1936. When he played for the world championship in 1907, he was soundly defeated by defending champion Emanuel Lasker. Marshall was not strong enough defensively to become a true world championship contender, but he nonetheless won several brilliant victories and also made important contributions to opening theory.

- Early Life And Career

- Cambridge Springs (1904)

- Match Versus Lasker (1907)

- U.S. Champion (1909-36)

- Legacy

Early Life And Career

Marshall was born in New York City but spent much of his youth in Montreal. Although he did not learn to play chess until the age of 10, he quickly developed into a strong player in the Montreal chess scene.

The game that Marshall played in Paris in 1900 against England’s Amos Burn became famous for Marshall’s telling of the story in which his opponent was unable to light his pipe before the game was over.

Marshall tied for third in this tournament with Geza Maroczy, behind the winner Lasker and second-place Harry Pillsbury.

Cambridge Springs (1904)

Marshall’s greatest victory may have been the Cambridge Springs tournament in 1904. He did not lose a single game out of 15, winning 11 to clear the 16-player field by two points over David Janowsky and the reigning world champion Lasker. Also in the field were Pillsbury and Jackson Showalter, who along with Marshall were the top three American players at this time.

Marshall’s victims included Janowsky in a 76-move Queen’s Gambit (below), one of Marshall’s five wins in the tournament as Black. He also won his games as White against Showalter (who finished fifth) and Pillsbury (tied for eighth).

Match Versus Lasker (1907)

In 1907 Lasker defended his championship title for the first time in a decade and did so against Marshall. The first player to win eight games would be the winner.

The match did not go well for Marshall, as he immediately dropped three games, two with the white pieces. Over the next eight games, he managed seven draws, but also lost for the fourth time in game eight. Starting with game 12, Marshall lost four in a row, the last of which gave Lasker a +8 -0 =7 victory.

Marshall wasn’t embarrassed in any particular game, other than the 21-move 14th contest. Although he lasted from 37 to 69 moves in his other defeats, he was clearly no match for Lasker.

Lasker defended his title three times in the next three years but never again against Marshall before losing to Jose Capablanca in 1921. (In 1909, Capablanca soundly defeated Marshall in a match, although no title was on the line.)

U.S. Champion (1909-36)

The United States chess championship was held by either Showalter or Pillsbury for most of the 1890s. Pillsbury was the last to claim it, doing so in 1898, and held the title until his death in 1906. Three years later, a match was finally arranged between Marshall and Showalter.

Marshall won the title easily. It began with three wins and a draw in the first four games before Showalter took the fifth game. But after two more draws, Marshall won three in a row and was well on his way to a +7 -2 =3 victory. Marshall won twice, including the final game, below, against Showalter's Albin Counter to the Queen's Gambit.

Marshall defended the U.S. Championship once, in 1923 against Edward Lasker (not to be confused with Emanuel, his distant relative). Lasker would prove a much more difficult opponent than the 1909 version of Showalter and immediately won the first two games.

But Marshall drew game three and then won two in a row to tie the match again. He lost the sixth game but immediately bounced back with a victory in game seven. The match got less bloody thereafter with draws in four of the next six games, but Marshall won the two exceptions, games 10 and 12. He never relinquished the lead, drawing game 13 before dropping game 14 but then drawing the final four games. Below, Marshall's final victory in game 12, which ultimately clinched the match.

Despite the closeness of this match—Marshall won 9½-8½—he never again defended his U.S. title, in large part due to demands that would-be challengers (including Lasker) found unreasonable. When the 1936 U.S. Championship tournament was held, Marshall did not participate and finally relinquished the title.

Although he did not defend his U.S. title but once, Marshall was an active tournament player throughout and played perhaps his best game at a tournament in 1912. As Black against Stefan Levitsky during the 18th German Chess Congress, Marshall won with a spectacular 23rd move, after which spectators reportedly showered the board with gold coins. (See “Best Game” below for the moves.)

Also during this period Marshall displayed his Ruy Lopez gambit against Capablanca in 1918. Capablanca actually won the game, but Marshall’s pawn sacrifice came to be a deeply studied and quite respectable response to the Ruy Lopez.

Legacy

Marshall’s greatest contribution to chess theory is his gambit in the Ruy Lopez. However, other openings bear his name as well, including two variations of the Queen’s Gambit: 1. d4 d5 2. c4 c6 3. Nc3 e6 4. e4 and 1. d4 d5 2. c4 Nf6. The first is another sacrifice, while the second is often seen at amateur levels but best avoided.

In the United States, Marshall’s legacy goes beyond his championship reign. In 1915 he helped open the chess club in New York that bears his name and led it until his 1944 passing. The Marshall Chess Club remains in operation, and several top American players were or are members, including Bobby Fischer and Fabiano Caruana. World Champion Magnus Carlsen often visits the club as well.

Marshall was one of the finest players in U.S. chess history. His opening ideas remain relevant today and his tactical prowess, as demonstrated against Levitsky and others, remains memorable.