4 Surprising World Chess Championship Upsets

How will you react if GM Ian Nepomniachtchi defeats GM Magnus Carlsen and becomes the next world champion of chess? Will you have seen it coming, or would it be one of the biggest upsets in world chess championship history?

Unexpected championship match results are not unprecedented. At some point, even the very best players will be knocked off of their pedestal—and they have been.

Here are four of the biggest world championship upsets in chess history, in chronological order.

- 1927: Alekhine Over Capablanca

- 1935: Euwe Over Alekhine

- 1984/85: Kasparov Over Karpov

- 2000: Kramnik Over Kasparov

- Conclusion

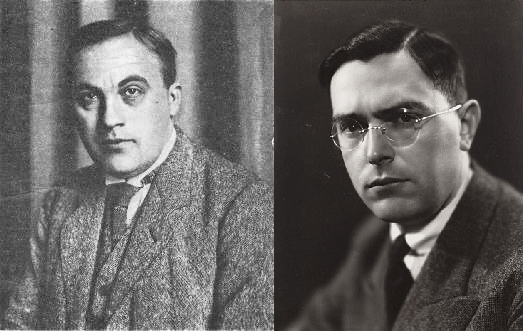

1927: Alekhine Over Capablanca

Earlier in 1927, Jose Raul Capablanca had dominated a tournament in New York, a quadruple round-robin he won with eight victories and 12 draws for a score of 14/20, 2.5 points ahead of second-place Alexander Alekhine. Capablanca won one of his four games against Alekhine, extending his undefeated lifetime record against the Russian, who became a French citizen during their match.

Capablanca dominated lots of tournaments. He hadn't lost a single tournament game from 1916-24, including in his 1921 championship match against Emanuel Lasker. In 1927 "Capa" was still widely considered to be the best player in the world and his unblemished personal record against Alekhine—before World War I, it wasn't even close, four wins and a draw for Capa in five games—did the public's perception of Alekhine's chances no favors.

According to Graeme Cree, Rudolf Spielmann predicted zero wins for Alekhine in the match, and future challenger GM Efim Bogoljubov predicted two. (By the way, if anyone has access to the 1927 American Chess Bulletin then send it the author's way please.)

So how did Alekhine pull it off? Let's let Fred Reinfeld describe the match ten years later, in the December 1937 Chess Review issue:

[Alekhine] had come to the conclusion (based on previous unfortunate experiences) that Capablanca could only be beaten by his own style. The result was a deadening succession of Orthodox Queen's Gambits, sometimes identical up to the 20th move, sometimes given up as a draw after the 20th move, without a single thought having been expended on the game. Many of the 'contests' were shams, were simply intermezzi between something really important. Thrills were noticeable by their absence, and the unfortunate impression arose that this was the essence of modern chess.

So not only was Alekhine a surprise winner, he did it in a surprising way by abandoning his preferred style. On one hand that shows admirable flexibility, yet even when he led 5-3 there were doubts about his chances (see Edward Winter here for that, and a lot more, about the match).

But he went right ahead and won the match, and then never played Capablanca in a match again.

1935: Euwe over Alekhine

Alekhine's world championship opponent after Capablanca and before GM Max Euwe was Bogoljubov, twice. Those matches were no contest for Alekhine, who beat "Bogo" a combined 19-8 in 1929 and 1934.

And how had Euwe done vs. Bogoljubov? As of 1935, their score against each other was 6-6 in 28 games. In match play, twice for the championship of some new organization called FIDE, Bogoljubov had twice won by a point.

So if Euwe couldn't beat Bogo, how could he beat Alekhine? Overall Alekhine led Euwe 6-3 lifetime just before they played their 1935 world championship match, including winning a training match in 1926.

It's no surprise that, writing in retrospect in the December 1935 issue of Chess Review, Reinfeld stated that "most players (including experts) pooh-poohed [Euwe's] chances." (These magazines, by the way, are available to everyone at the US Chess website.)

And as James R. Newman described in the same periodical a month later, once the match started, an Euwe win didn't seem to be any likelier: "After the first nine games of the match had been played, the almost universal prophecy among those who are supposed to be in the know in the chess world, that Dr. Alekhine would sweep everything before him, seemed to be coming true. The latter led by a score of 6 to 3, an enormous advantage and an almost insurmountable obstacle, particularly in this day of closely fought positional games, leading most often to draws." Newman's overall conclusion: "It cannot be denied that Dr. Alekhine's defeat was astounding."

In hindsight, Euwe's play in the early 1930s was world championship-caliber after all. By computer accuracy, he was the #1 player in the world for most of 1932-36; yes, even compared to Alekhine. And Euwe had even defeated Alekhine in their final game prior to the match, at Zurich 1934, something Alekhine himself did not do against Capablanca at New York in 1927.

Nonetheless, the result shocked the world. And it wasn't the last time the first nine games of a match did not portend its conclusion.

1984/85: Kasparov over Karpov

Fast forward half a century. The world championship has seen many strange sagas, and having 48 games thrown away as if they never happened is perhaps the strangest. Yet that's exactly what happened between GM Anatoly Karpov and GM Garry Kasparov in 1984/85.

Kasparov had never won a game against Karpov before, but they'd only played four times with three draws and the decisive game happening in 1975 when Kasparov was 12 and Karpov was world champion.

So, with the players rated fairly close on the official FIDE list, the chess world thought both players' chances were about even. For example, in Chess Life, GM Victor Kupreichik picked Karpov while GM Boris Spassky chose Kasparov. GM Alexei Suetin gave the players equal chances, while GM Mikhail Tal joked that the winner's name would begin with "Ka" and end in "ov."

Once Karpov took a 4-0 lead in just nine games, however, leaving him only two victories away from keeping his title, no one could have expected Kasparov to recover. Karpov even made the January 1985 cover of Chess Life at this point. (The issues were printed several weeks in advance of their issue date back then; Karpov took his 4-0 lead on October 5, 1984.) Referring to the sixth game in that issue, GM Leonid Shamkovich wrote: "In the future, many observers may regard this loss as fatal to Kasparov's chances in this match."

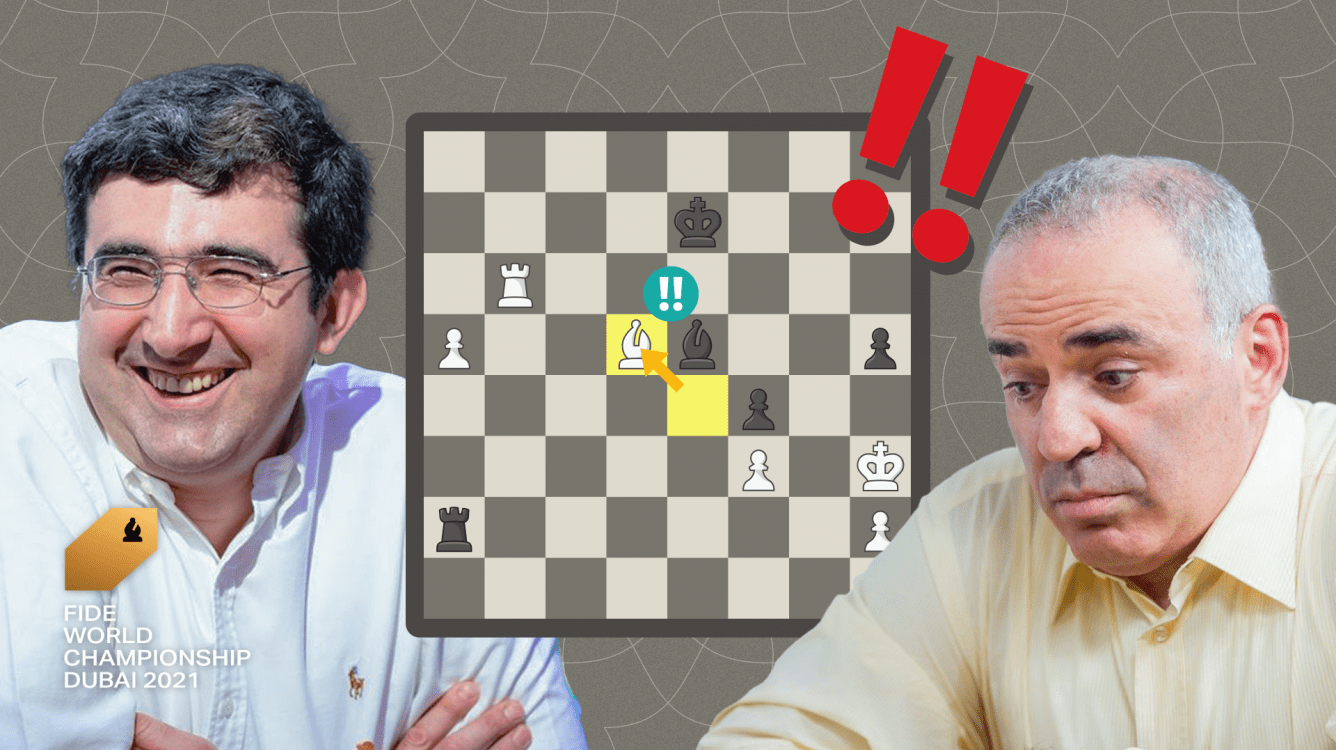

After that, another 39 games were played, of which 35 were drawn. Several of these draws were short non-contests but several went for dozens of moves. Meanwhile, three of the four decisive games went Kasparov's way, culminating in the 47th and 48th games of the match. Here, #48:

Karpov's condition got most of the press attention, but both players reportedly lost significant amounts of weight. Not in the good "I'm getting fit" way—would be a weird time to focus on that anyway—but in the less good "I'm under huge amounts of stress and can't get enough sustenance to compensate" way. Albeit that's not necessarily terribly unusual, let alone for a six-month match.

Regardless, the match was canceled by FIDE after game 48, even though neither player publicly supported the decision. A new match started in September 1985.

After getting all that well-earned experience against Karpov and a reset to the score, Kasparov's chances were much better in the new match. And indeed, he got it done by a score of 13-11 in 24 games, winning the final game on November 9, 1985 to become world champion more than a year after he had fallen behind 4-0. Call it a comeback or an upset, it was unprecedented and will almost certainly never happen again.

2000: Kramnik over Kasparov

In 1998, GM Vladimir Kramnik played a match against GM Alexei Shirov. The idea was for the winner to play GM Garry Kasparov for the classical world championship. The title was split at this time; for its part, FIDE was in the process of turning its title into a gigantic tournament that pleased nobody except its victors.

That match did not go well... for Kramnik, who lost two out of nine games without a win. Nonetheless, it was Kramnik who got the title bout against Kasparov after neither Shirov nor GM Viswanathan Anand secured sponsorship for one. (Anand had played Kasparov for the title, but in 1995.)

In one sense this outcome was reasonable: Prior to their match, the score in standard games between Kramnik and Kasparov was an even 3-3. Meanwhile, Shirov never won a single game against Kasparov at any time control in any year before, during, or after 2000. But Shirov had obvious and legitimate reasons to be disappointed not to get his chance.

Despite their score against each other, Kramnik's short-lived tie for the #1 FIDE rating in 1996, and their shared first place at Linares earlier in 2000, few expected Kasparov to lose to Kramnik. On the October 2000 rating list, Kasparov was rated an astounding 2849. Today that might seem merely great, but it was in fact absurdly great: Back then, only 10 players even had a mark of 2700, compared to 30-something players these days. Kramnik was #3 in the world at 2772, two points behind Anand and 28 points ahead of #6 Shirov.

Kasparov's ridiculous rating and aura of invincibility, as well as Kramnik's poor match record—in addition to Shirov, he'd lost to GM Gata Kamsky 4½-1½ in 1994 and to GM Boris Gelfand 4½-3½ in 1995—led few to suspect the eventual outcome.

But Kramnik also knew more about Kasparov's play than most, having been his second during the 1995 world championship match against Anand. That helped Kramnik to be famously able to out-prepare Kasparov in the opening, especially by using the Berlin Defense to the Ruy Lopez as a drawing weapon. How do you deal with a dangerous and dynamic player with astounding attacking and defensive capabilities? Kramnik elected to trade queens early by using the Berlin as Black, which turned out to be an excellent strategy—he won the match 2-0 in 15 games.

Kasparov didn't even win a single game in the match, settling for several quick draws. That was a good strategy in the unlimited match against Karpov in 1984-85, but rather less good in a match capped at 16 games. Kasparov drew all eight of his games as White in an average of 29.5 moves, including games of 24, 11, and 14 moves after he'd already fallen behind in the match. It was very unlike Kasparov, but Kramnik knew how to neutralize him and pulled off one of the biggest world championship upsets of all time.

Conclusion

So, how will Carlsen-Nepomniachtchi turn out? We have previews here from NM Matt Jensen and here from GM Gregory Serper, which should give you a better idea of how big an upset, or not, a Nepomniachtchi win might be.

What do you think is the biggest upset in world chess championship history? Let us know, and why! And remember to watch the 2021 World Championship on Chess.com starting this November.

Chess.com’s coverage is brought to you by Coinbase. Whether you’re looking to make your first crypto purchase or you’re an experienced trader, Coinbase has you covered. Earn crypto by learning about crypto with Coinbase Earn, power up your trading with Coinbase’s advanced features, get exclusive rewards when you spend with Coinbase Card, and much more. Learn more at Coinbase.com/Chess.