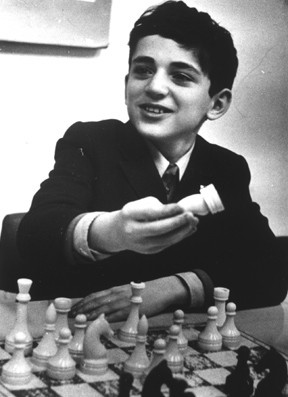

GM Garry Kasparov

Bio

Garry Kasparov is arguably the greatest chess player of all time. Born in Baku, Soviet Union (now Azerbaijan) in 1963, he quickly developed at Mikhail Botvinnik’s school, on his way to becoming the youngest champion in chess history in 1985. Always independent-minded, Kasparov split from FIDE in 1993, and would later become known outside of chess for his political activism after his 2005 retirement. Although no longer a professional player, he remains active in the chess scene as well.

- Pre-Championship Life and Career

- Becoming World Champion

- Staying World Champion

- Split from FIDE

- Post-Championship Career

- Post-Retirement Activities

- Legacy

Pre-Championship Life and Career

Kasparov was a very promising player from a very early age, as only such players made it to Botvinnik’s school. Under coaches such as Vladimir Makogonov and Alexander Shakarov, he developed to the point of winning the Soviet Junior Championship in 1976 and 1977. The World Junior title came in 1980. A share of first in the Soviet Championship came the next year.

CC BY-SA 3.0 licensing information at Wikimedia Commons.

Although Kasparov did not earn a spot in the 1981 championship cycle to dethrone Anatoly Karpov -- the Interzonals occurred in 1979 -- he was ready for the ’84 cycle. A score of +7 -0 =6 in the Moscow Interzonal earned Kasparov a spot in the Candidates matches. He first defeated Alexander Beliavsky 6-3 (+4 -1 =4). Next he would face Viktor Korchnoi, Karpov’s 1978 and 1981 challenger, in the semifinal.

Kasparov ended Korchnoi’s bid at a third straight challenge to Karpov with a +4 -1 =6 score. Only former champion Vassily Smyslov -- who, at 63 years old, was then three times Kasparov’s age -- now stood in Kasparov’s path to a match with Karpov.

The Candidates final was not close. Kasparov never lost a game, winning the third, fourth, ninth, and 12th games. A draw in Game 13 ended the match 8 ½ - 4 ½ in Kasparov’s favor.

Becoming World Champion

Kasparov entered the 1984 championship having played Karpov four times before, losing in 1975 (at 12 years old), and drawing three times in 1981. However, the start was a disastrous one for Kasparov, as he lost four of the first nine games. The format, as it had been for Karpov-Korchnoi matches in 1978 and ’81, was the first to six wins with draws not counting. Could youth really lose to experience this quickly?

The answer turned out to be not quite. Kasparov bore down to draw the next 17 games: not a strategy one could even try in a 24-game match, but an effective one in the 1984 format. In the 27th game, however, Karpov won, leaving him a single victory from a sweep.

It was not to be. First, Kasparov finally broke through for his first world championship win, and first win ever against Karpov, in Game 32.

Several more draws followed. Then, in Game 47, Kasparov won again. And in Game 48, again. The match score was now 5-3...but it was over. FIDE President Florencio Campomanes had declared it so, citing player health. The players would start from scratch in 1985, and unsurprisingly, the new match returned to the 24-game format.

Karpov once again took an early lead, but this time a more modest 2-1 through five games after Kasparov took the first game. Kasparov evened the match in Game 11. In the next game, he played an odd gambit from the Sicilian, which produced a quick draw. The next three games were drawn as well.

Then, in Game 16, Kasparov played perhaps the greatest single chess game anyone has ever produced. He went back to his Sicilian gambit, Karpov responded less accurately than before, and soon Kasparov’s pieces dominated the board.

Armed with a 4-3 lead, Kasparov went on to win Game 19 and draw the next two games. In Game 22, however, Karpov broke through in a Queen’s Gambit. Including draws, this put the match score at 11 ½ - 10 ½ in Kasparov’s favor. One loss for Kasparov in the final two games, and Karpov would tie the match 12-12 and retain his title. Kasparov held the draw in Game 23, needing just one more draw to clinch the title.

He did not draw Game 24: he won it.

Kasparov credited better preparation than Karpov for his win, which was largely admitted by Karpov as well; nonetheless Kasparov also credited Karpov with providing a "true fight" for the title. (Source: The World Chess Championship Karpov Kasparov Moscow 1985, Raduga Publishers 1986.)

It is, of course, unknown how the 1984 match might have ended. Perhaps Kasparov would have knocked down the door, or perhaps Karpov would have dug deep and found the sixth win. But now Kasparov was champion, and it was also not too late for him to set the record as the youngest ever. He was 22 years and seven months old, 11 months younger than Mikhail Tal had been in 1960.

Staying World Champion

Kasparov had now faced Karpov 72 times in the past 15 months, from September 1984 to November 1985. They would play another 48 world championship games in the next two years.

Karpov automatically got a rematch with Kasparov in 1986 thanks to the circumstances of 1984-85. Kasparov scored +4 -1 =11 early to start, but then dropped three straight games. A win in Game 22, however, was followed by two more draws to earn him his first title defense.

The world championship process somewhat reset in 1987 as the Interzonal and Candidates tournaments returned on their original schedule. Karpov was seeded in to the finals, however, where he defeated Andrei Sokolov.

The 1987 World Championship was arguably the most dramatic of the Kasparov-Karpov matches. As in 1985, Kasparov won once and lost twice in the first five games. This time, he came back to win the eighth and 11th games. A Karpov win and several more draws later, the score was tied at 11 with two games to play. However, Kasparov lost Game 23, leaving him in the unenviable position of absolutely requiring a win in the final contest, in order to tie the match and retain his title.

Kasparov pulled it off. Karpov achieved several exchanges, but Kasparov sacrificed a pawn to place a knight on e5. He eventually regained the pawn and then went up a pawn. With only four pawns left to three, all on the kingside, it was a difficult position to win. Nonetheless, after much maneuvering from Kasparov, Karpov called it quits.

After a whopping 120 Kasparov-Karpov games in four years, it was finally time for another three-year wait between championship matches. In 1990, Karpov would challenge Kasparov again. Relative to their previous matches, it was fairly easy for Kasparov this time. After winning Games 18 and 20, Kasparov was up 11-9 (+4 -2 =14). Although he would drop Game 23, a draw in the final game clinched the victory.

Again three years passed between championship matches, but business as usual was about to disappear again.

Split from FIDE

Nigel Short defeated Karpov in the semifinals of the 1993 Candidates tournament, then defeated Jan Timman to earn a match with Kasparov. Neither the champion nor challenger were comfortable with FIDE, and the result was ultimately a split in the championship. Kasparov and Short kept the 24-game format but played in London under the auspices of the Professional Chess Association (PCA). FIDE’s championship title reverted to Karpov without him having defeated Kasparov in a match; Karpov instead defeated Timman to regain the FIDE title.

Short was not nearly as prolific a player as Karpov, although he had beaten him to make it this far, and the hyper-competitive Kasparov was not one to let his guard down besides. He won five of the first nine games and coasted to a 12 ½ - 7 ½ victory. Kasparov defeated this split title once, in a match with Viswanathan Anand in 1995.

It would prove more somewhat difficult. It was also somewhat shorter than earlier matches, with the first player to score 10 ½ (draws still counting for half) winning the title. The first eight games were drawn before Anand broke through in Game 9.

Perhaps that lit a fire under Kasparov, who came right back in Game 10 to even the match. So thorough was his opening preparation that he needed only a couple of minutes for his first 20+ moves.

Then he won Game 11. And Game 13. And 14. Four draws later, he had a 10 ½ - 7 ½ win, the ninth game a distant memory.

Because the PCA could not retain sponsorships, it would be five years before Kasparov played another match to defend the championship. He wasn’t exactly sitting around biding his time, however.

In the second half of the 1990’s, Kasparov was at the forefront of computer and internet chess. Less famously than the match a year later, he played Deep Blue in 1996. He won that match comfortably, 4-2, despite losing the first game. Then came the 1997 match, which Kasparov dropped in dramatic fashion, after which IBM retired Deep Blue. As for then-nascent internet chess, Kasparov defeated “The World” in a game held by online vote in 1999.

Then there was the matter of the 1999 tournament at Wijk aan Zee. It was one of several tournaments Kasparov won in his career (here with a +8 -1 =4 score to beat Anand by a half point). Although it was the first time he had won this particular event, he would also win it in 2000 and 2001. But more notably, the 1999 Wijk tournament featured the game that rivaled Game 16 in 1985 for the best of his career and perhaps all time: a double rook sacrifice and a king hunt against Bulgaria’s Veselin Topalov.

Post-Championship Career

With Kasparov still a FIDE outsider, a championship match was organized between him and Vladimir Kramnik in 2000. In the previous years, negotiations for a match with Alexei Shirov and a rematch with Anand had proven fruitless. Meanwhile, Karpov continued to operate in the FIDE framework until 1999, when the championship format was changed to a large knockout tournament, in which he refused to play. But Kramnik would prove himself more than a legitimate challenger to Kasparov.

Kasparov’s Grunfeld Defense fell in Game 2, putting him in an early hole. And when he played the white pieces, Kramnik held him completely in check, mostly via the Berlin Defense to the Ruy Lopez (1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nf6 3. Bb5 Nf6). In Game 10, Kasparov was routed in just 25 moves after having earlier switched from the Grunfeld to the Nimzo-Indian against Kramnik’s 1. d4. Five games later, all draws, the match concluded with a Kramnik victory.

Kasparov would never hold claim to the title of world champion again, or even play in a match for it despite repeated attempts. However, he remained the highest-rated player in the world throughout his post-championship tenure.

Kasparov’s career came to an end at the Linares tournament in 2005. It was yet another tournament victory, his ninth at that particular site in Spain. (No one else won it more than three times until it was abandoned in 2010.) Unable to concentrate by his own admission, he lost the last official game of his career to Topalov. But what a career.

Post-Retirement Activities

Kasparov has become a prolific author, beginning with his My Great Predecessors series -- a five-volume collection of the games of the former world champions and other strong players, published from 2003-06 -- as well as four volumes of Modern Chess (much of it covering his matches with Karpov) and additional three volumes about his own chess career.

1st part of "My Great Predecessors"

Since then, he’s gone beyond chess to write three additional books: the part-biography, part-self-help How Life Imitates Chess, the geopolitics-focused Winter is Coming, and Deep Thinking about artificial intelligence. Winter is Coming was the product of Kasparov’s deep, longtime concern about Vladimir Putin’s effect on Russia and the world.

Kasparov’s disdain for FIDE leadership also continued. In 2010, Kasparov supported his former rival Karpov in a pursuit of the presidency of FIDE, held by Kirsan Ilyumzhinov. Karpov’s bid failed, and in 2014 Kasparov himself ran for the position, but was also defeated. Ilyumzhinov finally left the presidency of FIDE in 2018.

As for chess activities outside of FIDE politics, Kasparov has promoted the game internationally, especially through his Kasparov Chess Foundation. He has also been a coach for Magnus Carlsen (in 2009) and Hikaru Nakamura (2011). Additionally, Kasparov visits St. Louis often for the Rex Sinquefield-sponsored chess events there, sometimes commentating and even agreeing to participate in the St. Louis Rapid and Blitz in 2017, his first non-exhibition chess since 2005.

Legacy

Is Kasparov the best chess player of all time? Emanuel Lasker had a longer championship run and Bobby Fischer probably had a higher peak with his 6-0 wins over Mark Taimanov and Bent Larsen in the 1972 Candidates, but neither Lasker nor Fischer can match Kasparov’s combination of longevity and dominance. Jose Capablanca, like Fischer, was very dominant at his best, but his best covered less than a decade (although at least Capablanca kept playing). Carlsen has a chance to achieve both to similar degrees that Kasparov did, but can’t claim the longevity yet.

It’s a subjective question, but unlike in team sports, chess players have the advantage of playing their own games. They may have a team of seconds or rise with the help of a supportive infrastructure, but once across the table from their opponent, it’s all on them. Kasparov’s argument for best ever is at least as strong as anyone’s.

Even ignoring such debates, Kasparov introduced several opening innovations, as well as winning with openings that had lost favor, such as the Scotch Game (1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. d4) or Evans Gambit (1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bc4 Bc5 4. b4). His 1985 gambit against Karpov eventually proved refutable, but in that moment and several others, Kasparov’s willingness to try things led to brilliant victories. He was of course incredibly accurate as well, with the third best CAPS score among all-time champions, higher than any of his predecessors. His matches with Karpov were among the most exciting in chess history.

Whether you rank him #1 or not, Garry Kasparov is one of the few chess players of all time with a rightful claim to the title of best ever.