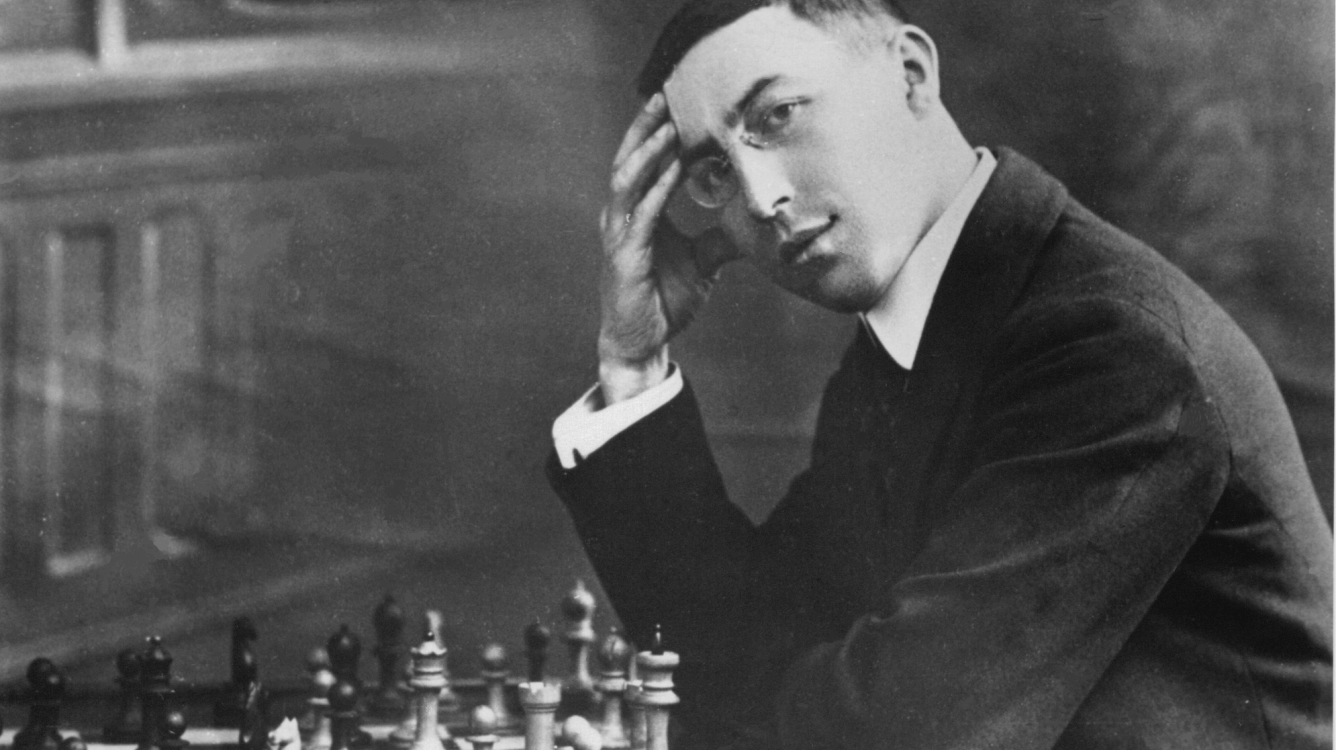

A Century of Chess: Akiba Rubinstein (from 1910-1919)

Rubinstein broke into the chess elite with his third-place finish at Ostend 1906. He won his first international tournament at Ostend-B 1907, followed shortly by Karlsbad. In 1909, he gave notice that he really was a cut above the rest of the chess world by winning, together with Lasker, the 1909 St Petersburg tournament, 3.5 points ahead of the next closest contestant.

There was something terrifying to other chess players about Rubinstein’s inexorable advance. Some of it was style — there was virtually nothing of Romanticism in the way he played; everything was positional, ‘scientific,’ machine-like. And some of it was personality — he seemed more than anybody else of his era (except maybe Nimzowitsch) to live entirely for chess, to have no sense of treating chess as a game or amusement. There was an element of anti-Semitism, or at least cultural snobbery too, in the way that Rubinstein was viewed by the rest of the chess world. “Deep out of the shadows, out of the Middle Ages, came Akiba Rubinstein. A dark squalid ghetto of Russia-Poland was the Bethlehem in which his spark of life was kindled,” ran a biography of him. A contemporary described him as being entirely a “chess man.”

That aversion to Rubinstein intensified when his mental illnesses became apparent. As far as I can tell, they began to manifest in the early 1910s, when he complained about being constantly chased by a fly. The mental issues got worse with time — with Rubinstein avoiding mirrors, absenting himself from the board whenever it was his opponent’s move so that his opponent wouldn’t be distracted by his presence, and eventually succumbing to full-fledged paranoia. In an era with limited sympathy for mental illness, Rubinstein came to be viewed as something of a cautionary tale of chess obsession, much as Morphy and Steinitz had been perceiving before him, the idea being that the overloading of one’s mind with chess could lead only to madness. And many of the fictional portrayals of masters in this era — ranging from Nabokov’s Luzhin Defense to Zweig’s The Royal Game to Canetti’s Auto-da-Fé — seem to be more or less directly influenced by this general prototype.

But in the early 1910s, Rubinstein appeared indomitable. He finished shared second at both San Sebastián 1911 and Karlsbad 1911 and then in 1912 had one of the best years that any chess player has ever had, winning four international tournaments. I have to say that I have been a little less impressed by Rubinstein’s play than many of his contemporaries were. To a great extent, he was an endgame specialist, realized that the state of endgame play in master chess was actually pretty low, and in game after game simply exchanged down to an ending and then outplayed his opponent. But he had other abilities too, of course. Primary among them was his skill in creating architecturally-sound positions, and then he made it look almost too easy, swatting aside attempted attacks or else building up a steady positional advantage. He seemed to be a specialist also in generating winning pressure along the d-file.

Lasker was critical of Rubinstein for having played too much chess in 1912, and, as so often, Lasker knew what he was talking about. In a sense, Rubinstein never fully recovered from his exertions that year. He took off 1913, which was a quiet chess year, and then he played in the St Petersburg 1914 tournament but choked, failing to qualify for the finals or to be inducted into the inaugural grandmaster class. To a surprising extent, that setback defined Rubinstein. The war curtailed chess, left everybody with the memory of that one tournament, and, because of it, Rubinstein seemed to fade out of the world championship discussion, with Capablanca now the presumptive challenger to Lasker.

Rubinstein would go on to have a long and productive career in chess. He was the world’s #3 or #4 nearly throughout the 1920s and his chess style became more attractive at that time — he was more willing to attack and to complicate — but he never again quite achieved the indestructible form that he had from 1909 to 1912.

Rubinstein's Style

1. Endgames

Most of the attention on Rubinstein is dedicated towards his play in rook-and-pawn endgames. "Rubinstein is the rook and pawn endgame of a game that God started with himself a thousand years ago," wrote Savielly Tartakower. But he was as deadly in other endgames, playing with unending precision where other players succumbed to boredom or restlessness.

2. Architecture

Rubinstein played the opening with almost absurd humility, in some cases passing up golden attacking opportunities, in order to make his position as structurally sound as possible. One of my favorite quotes about him describes his style as being like an arch in which stone is in its perfect place. Once that position was established, Rubinstein was able to withstand any attack. He was also able to exploit infinitesimal weaknesses in an opponent’s position to gradually infiltrate.

3. The d-file

For some reason, many of Rubinstein’s games centered on d-file pressure. I think the point was that his positions were so solid and centralized that he was able to bring all his position to bear on an opponent’s center and then to exploit any available open line.

Rubinstein in the Opening

As white, Rubinstein played the opening placidly — the Queen’s Pawn Game and book lines in the Queen’s Gambit. Apart from a handful of aberrations — the surprise of the Budapest Gambit at Berlin 1918, a Dutch Defense that Spielmann unfurled against him, and a Nimzo-Indian from Alekhine — Rubinstein was close to unassailable with 1.d4 and went a long way to establishing 1.d4 as ‘the strategist’s opening.’ As black, his leading contribution was the Rubinstein French, which — at least in the view of Gyula Breyer — virtually negated 1.e4.

Sources: The vital source on Rubinstein is Donaldson and Minev's two-volume The Life and Games of Akiva Rubinstein. There are many other books on him but that one is the encyclopedia.